Cirrhosis - InDepth

Highlights

Causes of Cirrhosis

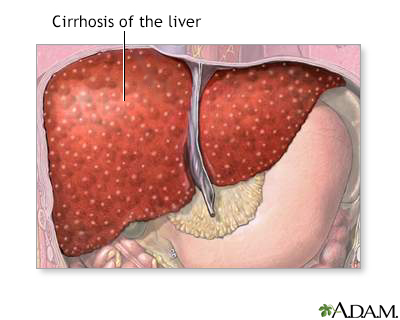

Cirrhosis is a liver disease characterized by permanent scarring of the liver that interferes with its normal functions. Causes include:

- Alcohol use disorder

- Chronic hepatitis B, C, and D

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Bile duct disorders such as primary biliary cirrhosis (currently called primary biliary cholangitis) and primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which includes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)

- Metabolic disorders such as hemochromatosis, Wilson disease, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

- Budd-Chiari syndrome

- Parasitic infections such as schistosomiasis

- Glycogen storage diseases such as galactosemia

- Numerous medications including methotrexate, azathioprine, statins, antibiotics such as erythromycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate, antifungal drugs, niacin, allopurinol, and antiviral agents used to treat HIV

Complications

Cirrhosis can cause many serious complications including:

- Ascites (fluid buildup in the abdomen)

- Variceal hemorrhage, severe bleeding from varices (enlarged veins in the esophagus and upper stomach)

- Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, a severe infection of the membrane lining of the abdomen

- Hepatic encephalopathy, impaired mental function caused by buildup in the body of toxins such as ammonia

- Hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer

- Hepatorenal syndrome, when kidney failure occurs along with severe cirrhosis

Dietary and Lifestyle Changes

Anyone who has cirrhosis can benefit from certain lifestyle interventions. These include:

- Stop drinking alcohol.

- Restrict dietary salt.

- Follow a healthy diet plan.

- Get vaccinations for influenza, hepatitis A and B, and pneumococcal pneumonia (if recommended by your doctor).

- Inform your health care provider of all prescription and nonprescription medications, and any herbs and supplements, you take or are considering taking.

Treatment

Cirrhosis is considered an irreversible condition. Treatment focuses on slowing the progression of liver damage and reducing the risk of further complications. Your doctor will treat any underlying medical conditions that are the cause of your cirrhosis.

If liver damage progresses to liver failure, some people may be candidates for liver transplantation. Liver donations can come from either a cadaver or from a living donor (who can donate part of their liver). People with cirrhosis who have a liver transplant have very good chances for survival.

Introduction

Cirrhosis is scarring of the liver and poor liver function. It results from various disorders that damage liver cells over time. Eventually, damage becomes so extensive that the normal structure of the liver is distorted and its function is impaired.

Cirrhosis is the end result of long-term liver damage. Alcohol abuse, and chronic hepatitis B and C, are the leading causes of cirrhosis. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is also being recognized as a major cause of cirrhosis.

Scarring

The main damage in cirrhosis is triggered by scarring that occurs from inflammation and injuries due to alcohol, viruses like hepatitis B and C, or other damage. The scar tissue and other changes in liver cells gradually replace healthy liver tissue and act like small dams to alter the flow of blood and bile in and out of the liver. The initial stage of light to moderate scarring in the liver is called fibrosis. As the scarring becomes more severe and extensive, cirrhosis occurs.

Altered Blood and Bile Flow

Liver scarring causes changes in blood and bile flow that have consequences throughout the body. In cirrhosis:

- The small blood vessels and bile ducts in the liver narrow (constrict). Blood vessels in other organs, including the kidney, also narrow.

- Blood flow coming from the intestine into the liver is slowed by the narrow blood vessels. It backs up through the portal vein and seeks other routes.

- Enlarged, abnormally twisted and swollen veins called varices form in the stomach, the lower part of the esophagus, and at times the rectum. They transport the blood diverted from the liver.

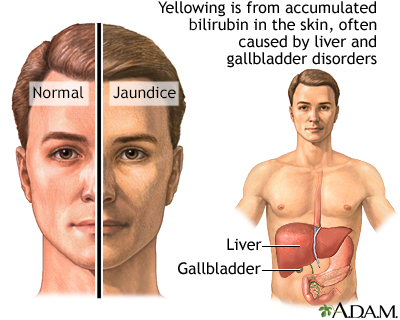

- Bilirubin, a substance found in bile, also builds up in the bloodstream, resulting in jaundice, a yellowish discoloration of the skin and eyes, as well as dark-colored urine.

- Fluid buildup in the abdomen (called ascites), and swelling in the legs (edema) occur.

Functions of the Liver

The liver is the largest internal organ in the body. In a healthy adult, it weighs about 3 pounds. It is located below the diaphragm and occupies the entire upper right side of the abdomen.

The liver performs several vital functions, including:

- Processing Healthful Nutrients. The liver processes (metabolizes) and stores all of the nutrients the body requires, including sugars, fats, minerals (like iron and copper) and vitamins.

- Producing Proteins. The liver is the body's "factory" where many important proteins, such as albumin, are made. The liver also produces essential proteins for blood clotting.

- Producing Bile. The liver produces bile, which is important for digestion. Bile is a green-colored fluid that helps the body absorb fats and fat-soluble vitamins. Bile contains bilirubin, a yellow-brown pigment produced from the breakdown of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying component in red blood cells.

- Eliminating Toxins. An important job of the liver is to make toxic substances in the body harmless. These include substances made by the body (such as ammonia and by-products of digestion) and substances you may ingest (such as alcohol and drugs).

Causes

Alcohol Use Disorder

Chronic alcohol use may in some individuals cause alcoholic liver disease (also called alcohol-induced liver disease). Alcoholic liver disease includes fatty liver (build-up of fat cells in the liver), alcoholic hepatitis (inflammation of the liver caused by heavy drinking), and alcoholic cirrhosis. In the liver, alcohol converts to toxic chemicals that trigger inflammation and tissue injury. This process can lead to cirrhosis.

Chronic Viral Hepatitis

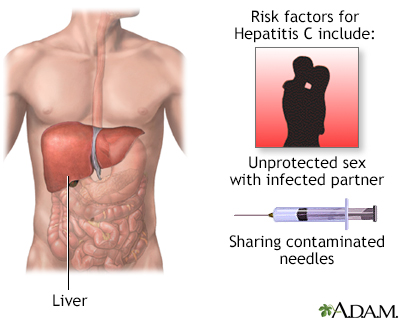

Chronic viral hepatitis, both hepatitis B and hepatitis C, is another major cause of cirrhosis. Chronic hepatitis C is a more common cause of cirrhosis in developed countries, while hepatitis B is a more common cause of cirrhosis worldwide, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia. People with chronic hepatitis B who are co-infected with hepatitis D are especially at risk for cirrhosis. The longer a person has chronic hepatitis, the greater the risk for eventually developing cirrhosis.

Hepatitis viruses produce inflammation in liver cells, causing injury or destruction. If the condition is severe and long-term, the cell damage becomes progressive, leading to severe scarring of the liver.

Hepatitis C is caused by a virus that causes inflammation in the liver, which may lead to cirrhosis. Consumption of alcohol enhances the damage done to the liver by the hepatitis C virus. The people at greatest risk of contracting and spreading hepatitis C are those who share needles for injecting drugs. People who have sex with multiple partners are also at increased risk of contracting hepatitis C. People who receive blood transfusions contaminated with hepatitis C virus are at great risk of developing active hepatitis.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis, like other autoimmune disorders, develops when a misdirected immune system attacks the body's own cells and organs. People who have autoimmune hepatitis also often have other autoimmune conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, scleroderma, inflammatory bowel disease, glomerulonephritis, and hemolytic anemia. Autoimmune hepatitis typically occurs in women ages 15 to 40.

Bile Ducts Disorders

Disorders that block or damage the bile ducts can cause bile to back up in the liver, leading to inflammation and cirrhosis. These diseases include primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (Primary biliary cholangitis)

Up to 95% of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) cases occur in women, usually around age 50. In people with PBC, the immune system attacks and destroys cells in the liver's bile ducts. Like many autoimmune disorders, the causes of PBC are unknown.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic disease that mostly affects men, usually around age 40. The cause is unknown, but immune system defects, genetics, and infections may play a role. Most patients with PSC also have inflammatory bowel disease.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) resembles alcoholic liver disease, but it occurs in people who do not drink a lot of alcohol. NAFLD is the most common liver disease in the United States.

NAFLD is actually a progressive spectrum of liver diseases that include:

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) or fatty liver is the earliest stage of NAFLD. It is marked by the presence of fat in the liver (steatosis), but liver damage has not occurred. While a fatty liver is not normal, NAFL is not considered a serious condition.

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the next stage of NAFLD. NASH is characterized by liver inflammation and injury, as well as a fatty liver. NASH is dangerous because it can lead to the scarring of the liver associated with cirrhosis. NASH is one of the leading causes of cirrhosis.

- Cirrhosis is the final irreversible stage of NAFLD.

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are the two main causes of NAFLD. Metabolic syndrome is another major factor. Metabolic syndrome is a collection of risk factors that include:

- Abdominal obesity

- Unhealthy blood lipid levels

- High blood pressure

- Insulin resistance

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is usually benign and very slowly progressive. But, in certain people, it can lead to cirrhosis and eventual liver failure. NAFLD also increases the risk for heart disease, which is the leading cause of death for these people.

Hereditary Disorders

Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis is a disorder of iron metabolism. This disease interferes with the way the body normally handles iron. People with hemochromatosis absorb too much iron from the food they eat. The iron overload accumulates in organs in the body. When excess iron deposits accumulate in the liver, they can cause cirrhosis.

Other Hereditary Disorders

Other inherited diseases that can cause cirrhosis include Wilson disease (which causes an accumulation of copper in the body), alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (a genetic disorder caused by defective production of a particular enzyme), and glycogen storage diseases (a group of disorders that cause abnormal amounts of glycogen to be stored in the liver).

Other Causes

Other causes of cirrhosis include:

- Schistosomiasis, a disease caused by a parasite found in Asia, Africa, and South America.

- Long-term or high-level exposure to certain chemicals and drugs, including arsenic, methotrexate, toxic doses of vitamin A, and certain prescription medications.

Symptoms

Cirrhosis is divided into two stages -- compensated and decompensated:

- Compensated cirrhosis. Means that the body still functions fairly well despite scarring of the liver. Many people with compensated cirrhosis experience few or no symptoms.

- Decompensated cirrhosis. Means that the severe scarring of the liver has damaged and disrupted essential body functions. People with decompensated cirrhosis develop many serious and life-threatening symptoms and complications.

Early stages of compensated cirrhosis may cause few or no symptoms. When symptoms do begin, they may include:

- Fatigue and loss of energy.

- Loss of appetite and weight loss.

- Nausea or abdominal pain.

- Muscle cramps, more likely to be at night.

- Spider angiomas may develop on the skin. These are pinhead-sized red spots from which tiny blood vessels radiate.

As cirrhosis progresses to a decompensated stage, people may develop the following symptoms:

- Fluid buildup in the abdomen (ascites) due to high pressure in the blood vessels of the liver.

- Swelling in the legs, feet, and hands (edema) due to low levels of blood albumin and poorly functioning kidneys.

- Stretched and swollen blood vessels (varices) in the esophagus and stomach due to increased pressure in the portal vein.

- Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice) due to buildup of bilirubin.

- Itching (pruritus) due to the buildup of bile products.

- Easy bruising and excessive bleeding because the liver stops producing blood clotting factors (coagulopathy).

- Swelling of breasts (gynecomastia) and shrunken testicles in men, or menstrual abnormalities in women due to disruption in the liver's regulation of sex hormones.

- Blotchy red palms of the hands (palmar erythema) and red spider-like veins (spider angioma), which are also caused by sex hormone dysregulation.

Some of these symptoms can lead to serious complications.

Jaundice is a condition produced when excess amounts of bilirubin circulating in the bloodstream dissolve in the layer of fat underneath the skin, causing a yellowish appearance of the skin and the whites of the eyes.

Complications

A damaged liver affects almost every bodily process, including the functions of the digestive, hormonal, and circulatory systems. Decompensated cirrhosis increases the risk of serious and potentially life-threatening complications.

Portal Hypertension

The most serious complications of cirrhosis are those associated with portal hypertension. The portal vein carries blood from the intestine to the liver. High pressure in the portal vein develops when scarring in the liver blocks this flow of blood. This condition is called portal hypertension.

Portal hypertension causes some of the most serious complications of cirrhosis. Ascites, bleeding varices, hepatic encephalopathy, and enlarged spleen are all associated with portal hypertension.

Ascites and Related Complications

Ascites is fluid buildup in the abdominal cavity. It is caused by a combination of portal hypertension and low albumin levels. Albumin is a protein produced by the liver. Symptoms include:

- Swelling of the belly and ankles

- Abdominal discomfort

- Rapid weight gain

If fluid accumulates in the lungs, it can cause problems with breathing. Although ascites itself is not fatal, it can lead to other more serious problems.

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a complication of ascites. It is a life-threatening bacterial infection of the membrane that lines the abdomen. Symptoms include confusion and altered mental status, fever, chills, and abdominal pain. Certain medications, such as proton pump inhibitors (used for treating acid reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease), may increase the risk for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in people with cirrhosis.

Ascites and portal hypertension can also cause kidney function to rapidly deteriorate.

Hepatorenal syndrome occurs when the kidneys drastically reduce their own blood flow in response to the altered blood flow in the liver. It is a life-threatening complication that can be fatal unless liver transplantation is performed. Symptoms include:

- Jaundice

- Decrease in urine volume

- Mental changes, such as delirium and confusion

Variceal Bleeding

Portal hypertension causes the development of varices, veins that enlarge to provide an alternative pathway for blood diverted from the liver. Varices usually form in the esophagus. They can also form in the upper stomach.

Varices pose a high risk for rupture and bleeding because they are thin-walled, twisted, and subject to high pressure. When varices rupture and bleed they can cause massive bleeding, a life-threatening event marked by black, tarry, or bloody stools, or vomiting of blood.

Enlarged Spleen (Splenomegaly)

Portal hypertension can affect blood flow in the spleen causing it to become enlarged (splenomegaly). When the spleen cannot function properly, levels of blood platelets and white blood cells are reduced. These blood problems increase the risk for infection and excessive bleeding.

Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is impaired brain function due to liver damage. It is caused by a buildup of harmful intestinal toxins in the blood, particularly ammonia, which then accumulate in the brain.

Early symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy include confusion, forgetfulness, and trouble concentrating. Other symptoms may include fruity-smelling bad breath and tremor. In late stages, hepatic encephalopathy can result in coma.

Liver Cancer

People with cirrhosis have an increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer. Hepatitis B and C, alcoholism, hemochromatosis, primary biliary cholangitis, and NASH, which are all causes of cirrhosis, are some of the major risk factors for liver cancer. Cirrhosis due to hepatitis C is the leading cause of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States.

Diagnosis

Cirrhosis is diagnosed on the basis of a physical exam, medical history, blood tests, and imaging tests. A liver biopsy may be performed to confirm a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

Physical Exam

In a physical examination the doctor will evaluate:

- How the liver feels. The liver is often enlarged in early stages of cirrhosis.

- If the abdomen is swollen. The doctor will check for signs of fluid (ascites) by tapping the flanks and listening for a dull thud, and feeling the abdomen for a shifting wave of fluid.

- Other signs of cirrhosis such as jaundice, muscle wasting, mental status, and (in male patients) breast enlargement.

Medical History

A medical history will indicate risk factors for cirrhosis. People with a history of alcoholism, hepatitis B or C, or certain other medical conditions are at high risk.

Blood Tests

Blood tests are used to measure liver enzymes associated with liver function. Enzymes known as aminotransferases, including aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT), are released when the liver is damaged.

Blood tests may also measure:

- Serum albumin concentration. Albumin is a protein made in the liver. Serum albumin measures the amount of this protein in the blood (low levels indicate poor liver function).

- Alkaline phosphatase (ALP). High ALP levels can indicate bile duct blockage.

- Bilirubin. Bilirubin, a red-yellow pigment that is normally metabolized in the liver and then excreted in the bile. A damaged liver cannot process bilirubin, and blood levels of this substance rise.

- Prothrombin time (PT). The PT test measures in seconds the time it takes for blood clots to form (the longer it takes the greater the risk for bleeding).

- Creatinine. High levels of creatinine indicate impaired kidney function.

Imaging Tests

Ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan may be used to determine the extent of scarring in the liver and to check for signs of liver cancer. A newer imaging method called transient elastography measures liver stiffness and may provide a non-invasive alternative to liver biopsy to demonstrate the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis. This technique is most often done using ultrasound. A score will be reported to reflect the severity of fibrosis thought to be present. The METAVIR score is widely used reporting five stages, F0 (no fibrosis) through F4 (cirrhosis).

Liver Biopsy

A liver biopsy is not always needed for diagnosis of cirrhosis. It may be performed for confirmation if other tests are inconclusive. A liver biopsy can also help determine the cause of cirrhosis, the extent of damage, and treatment options.

A biopsy involves a doctor inserting a thin biopsy needle, usually guided by ultrasound, to remove a small sample of liver tissue. Local anesthetic is used to numb the area. You may feel pressure and some dull pain. The procedure takes about 20 minutes.

The biopsy may be performed using various approaches, including:

- Percutaneous liver biopsy. Uses a needle inserted through the skin over the liver area to obtain a tissue sample from the liver.

- Transjugular liver biopsy. Uses a catheter (a thin tube) that is inserted in the jugular vein in the neck and threaded through the hepatic vein (which leads to the liver). A needle is passed through the tube, and a suction device collects liver samples.

- Laparoscopy. Is a procedure in which the doctor makes a small abdominal incision and inserts a thin tube that contains a tiny camera to view the surface of the liver. The doctor can place small surgical instruments through the tube to take a tissue sample.

Other Tests Used to Detect Complications of Cirrhosis

Endoscopy

Endoscopy may be used to check for esophageal varices. In this test, a fiber-optic tube is inserted down the throat. The tube contains a tiny camera to view the inside of the esophagus, where varices are most likely to develop.

Paracentesis

Paracentesis is performed to determine the cause of ascites. This procedure involves using a thin needle to withdraw fluid from the abdomen.

Tests for Liver Cancer

Your doctor may recommend you have regular screening tests to check for the development of liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma). These tests include a blood test to check for levels of alpha-fetoprotein and an imaging test (ultrasound, MRI, or CT scan).

Treatment

If caught early enough, the early stages of liver scarring (fibrosis) can sometimes be treated to reduce inflammation and prevent the development of cirrhosis. Once cirrhosis occurs, it is generally considered an irreversible condition.

Treatment goals are to slow the progression of liver damage and reduce the risk of further complications. There are currently no drugs available to treat severe liver scarring, although researchers are investigating various anti-fibrotic drugs.

Dietary and Lifestyle Changes

Everyone with cirrhosis can benefit from certain types of lifestyle interventions. These include:

- Stop drinking alcohol. It is very important for people with cirrhosis to completely abstain from alcohol.

- Restrict dietary salt. Sodium (salt) can increase fluid buildup in the body. Follow a low-sodium diet with plenty of fresh vegetables and fruits and avoid eating processed foods.

- Eat a healthy diet. People with cirrhosis are usually malnourished and require increased calories and nutrients. Your doctor may suggest you take a vitamin supplement.

- Get vaccinated. Vaccinations (such as hepatitis A, hepatitis B, influenza, pneumococcal pneumonia) are important. Ask your doctor which vaccinations you need.

- Discuss all medications with your doctor. Before you take any medications, ask your doctor if they are safe for you. Liver damage affects the metabolism of drugs. Opioids, sedatives, anti-anxiety drugs, and proton pump inhibitors can trigger serious complications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and naproxen should not be used because they can trigger bleeding, worsen cirrhosis, and potentially cause kidney failure. In recommended doses, acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) is a safer choice for pain management.

- Inform your doctor of any herbs or supplements you are considering taking. Certain types of herbal remedies (kava, chaparral, kombucha mushroom, mistletoe, pennyroyal, and some traditional Chinese herbs) can increase the risk for liver damage. Although some herbs, such as milk thistle (silymarin) have been studied for possible beneficial effects on liver disease, there is no scientific evidence that they can help.

Recognizing Signs of Dangerous Complications

People with cirrhosis are susceptible to infections and bleeding, both of which can be life threatening. Contact your doctor's office or go to the emergency room if you experience any of the following symptoms:

- Fever (temperature greater than 101°F or 38.3°C)

- Confusion that is new or suddenly becomes worse

- Vomiting more than once a day

- Rectal bleeding, black, tarry stools, vomiting blood or dark "coffee ground" material, or blood in the urine

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal or chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Abdominal swelling or ascites that is new or suddenly becomes worse

- Jaundice (yellowing skin or eyes) that is new or suddenly becomes worse

Treatment of Underlying Conditions

Treatment for cirrhosis depends on the cause of cirrhosis. In some cases, treatment of an underlying condition may help reverse early-stage cirrhosis.

Chronic Hepatitis

Many types of antiviral drugs are used to treat chronic hepatitis B. Treatment for chronic hepatitis C depends on the genotype. Treatment options for hepatitis C are constantly evolving as new drugs are approved. During the past few years, several new combination pills which are well tolerated and are very successful in clearing hepatitis C from those infected have been introduced. Among these are Harvoni, Zepatier, Epclusa, Vosevi, and Mavyret. Successful treatment of hepatitis can sometimes lead to regression of cirrhosis.

Autoimmune Hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is treated with the corticosteroid prednisone and also sometimes immunosuppressants, such as azathioprine (Imuran).

Bile Duct Disorders

Ursodeoxycholic acid (Actigall, generic), also known as ursodiol or UDCA, is used for treating primary biliary cholangitis, but it does not slow the progression of cirrhosis. The newest FDA approved drug for treating primary biliary cholangitis is obeticholic acid (Ocaliva); however, this drug should not be used in advanced cirrhosis. Itching is usually controlled with drugs such as cholestyramine (Questran, generic) and colestipol (Colestid). Antibiotics for infections in the bile ducts and drugs that affect the immune system (prednisone, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate) may also be used. Surgery may be needed to open up the bile ducts. Liver transplantation may be used to treat end stage PBC and has been quite successful.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)

Weight reduction through diet and exercise, and diabetes and cholesterol management are the primary approaches to treating these diseases.

Hemochromatosis

Hemochromatosis is treated with phlebotomy, a procedure that involves removing about a pint of blood once or twice a week until iron levels are normal.

Treatment of Complications

Treatment of Ascites

First-line treatment of people with ascites (fluid accumulation in the abdomen) involves:

- Dietary salt restriction (generally less than 1,500 mg/day of sodium).

- Drug treatment with diuretics. A combination of spironolactone and furosemide is used. Your doctor must be careful to avoid doses that remove fluid too rapidly.

- Discontinuing all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Other drugs that may be harmful for patients with ascites are certain blood pressure medications, including ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

- Fluid restriction is usually not necessary unless sodium levels in the blood are low.

- Liver transplantation may be considered.

Treatment for Recurring or Refractory Ascites

People with ascites that do not respond to diuretics (refractory ascites) may be treated with the drug midodrine (Orvaten, generic) to reduce ascitic fluid. If they do not respond to this drug treatment, they may require other procedures to reduce fluid:

- Large-volume paracentesis, which involves using a thin needle to withdraw fluid from the abdomen, may be used for ascites refractory to treatment or when complications are present. This may have to be repeated.

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) uses a stent placed in veins in the middle of the liver to keep open a passage connecting the hepatic and portal veins. This helps reroute blood around the scarred liver. In the procedure, a long needle is inserted into the jugular vein in the neck and passed down to the hepatic and portal veins. Alternatively, a peritoneovenous shunt may be used.

- Liver transplantation.

Treatment of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis

People with ascites who have high white blood cell counts should receive intravenous or oral antibiotic therapy. People who have had an episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are usually treated with long-term antibiotic therapy to prevent further infection, but doctors must also consider the risk for drug resistance.

Treatment of Hepatorenal Syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome can occur in patients with ascites. This is a life-threatening condition in which kidney failure develops because of altered blood flow in the liver. People with hepatorenal syndrome are usually treated with intravenous infusion of albumin or with the drug pentoxifylline. Liver transplantation is the only treatment currently capable of reversing the course of this complication.

Treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy

The first step in managing encephalopathy (damage to the brain) is to treat any precipitating cause, such as:

- High ammonia levels

- Bleeding

- Low oxygen

- Dehydration

- Infection

- Use of sedatives

Protein-restricted diets used to be recommended to lower ammonia production. However, extreme protein restriction can cause malnutrition and be harmful. Guidelines now recommend that people receive adequate protein intake and have small meals throughout the day including a late-night snack of complex carbohydrates.

Diets rich in vegetables and fiber are also important. The laxative lactulose, given as a syrup or enema, is used to empty the bowels and to help improve mental status. The antibiotic rifaximin (Xifaxan) may be added for people who do not improve with lactulose alone. Sedatives and narcotic medications and those containing ammonium (such as certain antacids) should be avoided.

Other therapies may also be recommended. People who are hospitalized for hepatitis-related encephalopathy may need intravenous or tube feedings or require a shunt procedure.

Treatment of Variceal Bleeding

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention means treating the varices before they have bled. Varices that are present in the esophagus, stomach, or intestines are always at risk of bleeding. Beta-blockers drugs, which are commonly used to treat high blood pressure, may be given to prevent bleeding.

People with medium-to-large varices that have not bled may be treated with a surgical procedure called endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). EVL is also called band ligation. It involves inserting an endoscope down through the esophagus. Latex bands are wrapped around the bleeding varices to shut off the blood supply.

Treatment

When varices located in the digestive tract begin to bleed (variceal hemorrhage), it is a life-threatening situation. The first step is to immediately achieve normal blood clotting (hemostasis) in order to stop the current bleeding episode. Blood transfusions are usually required.

The main treatment for variceal hemorrhage is a drug that tightens blood vessels (vasoconstrictor) such as octreotide (Sandostatin, generic). Medical procedures to stop bleeding include endoscopic variceal ligation (described above). An alternative procedure is endoscopic sclerotherapy. In endoscopic sclerotherapy, the endoscopic tube is inserted through the mouth and a sclerosant (a solution that toughens the tissue around the variceal blood vessels) is injected to stop the bleeding.

If these treatments do not control the bleeding, or bleeding recurs, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure can be performed. (For more information on TIPS, see "Treatment of Ascites" above.) However, this procedure can increase the risk for encephalopathy.

Another procedure, called balloon tamponade, may be used to temporarily control bleeding prior to the TIPS procedure. Balloon tamponade is performed only for bleeding that cannot be controlled by drugs or endoscopy. It involves inserting a tube through the nose and down through the esophagus until it reaches the upper part of the stomach. A balloon at the tube's end is inflated and positioned tightly against the esophageal wall. It is usually deflated in about 24 hours. Balloon tamponade poses a risk for serious complications, the most dangerous being rupture of the esophagus.

Secondary Prevention

People who survive an episode of variceal bleeding, need to be treated to prevent bleeding recurrence. They are prescribed either a combination of a nitrate drug and a beta-blocker or a beta-blocker alone. Several sessions of endoscopic variceal ligation may also be performed over the course of several months. The TIPS procedure may be recommended if bleeding recurs despite drug and endoscopic therapy. Liver transplantation may also be an option.

Treatment of Septic Shock

Septic shock is a life-threatening condition that occurs when a severe bacterial infection causes extremely low blood pressure. It is very important that people with cirrhosis and septic shock receive immediate and appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Liver Transplantation

When cirrhosis progresses to end-stage liver disease, liver transplantation may be an option. Transplantation is not necessary or appropriate for all people with cirrhosis.

A scoring system called Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) is used to determine which patients are most in need of a donor liver. A MELD score predicts 3-month survival based on laboratory tests of creatinine, bilirubin, and blood-clotting time. Priority is given to people who are most likely to die without a liver transplant.

Most liver transplants are performed using deceased-donor organs. Unfortunately, there are many more patients waiting for liver transplants than there are available organs from deceased donors. Living-donor liver transplantation is another option. In living-donor transplantation, surgeons replace the person's diseased liver with a part of the liver taken from a live donor. The donor's liver regenerates to full size within a few weeks of surgery, and the recipient's liver also regrows. This procedure produces excellent results, but there are some risks for the donor.

Transplantation surgery generally takes 4 to 12 hours to perform, and patients stay in the hospital for up to 3 weeks after the surgery. Most people return to normal or near-normal activities 6 to 12 months following the transplant. For the rest of their lives, they will need to take immunosuppressive medication to prevent rejection.

Current 5-year survival rates after liver transplantation are about 80%, depending on various factors. People report improved quality of life and mental functioning after liver transplantation. In researching transplant centers, ask how many transplants they perform each year and their survival rates as well as the average waiting time for a transplant. Compare those numbers to those of other transplant centers.

Liver Transplantation for People with Viral Hepatitis

One of the primary problems with performing liver transplantation in patients with viral hepatitis is recurrence of the virus after transplantation. Recurrence occurs more often with hepatitis C than hepatitis B. Pretreatment with antiviral drugs, along with life-long immune globulin injections after transplant, is very successful in reducing the risk for recurrence in hepatitis B. Pretreatment with new drugs such as sofosbuvir is showing promise in preventing recurrence in hepatitis C.

Liver Transplantation for People with Alcoholic Liver Disease

Liver transplantation is controversial for people with alcoholic liver disease. Most transplant centers recommend that people achieve at least 6 months of sobriety before being considered for a transplant. People with alcohol dependence who may need a liver transplant should meet with a mental health professional for evaluation of psychological problems, and to get help setting goals for addiction treatment.

Resources

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases -- www.niddk.nih.gov

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases -- www.aasld.org

- American Liver Foundation -- www.liverfoundation.org

- American Gastroenterological Association -- www.gastro.org

- United Network for Organ Sharing -- unos.org

- US government organ donor site -- www.organdonor.gov

References

Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):325-336. PMID: 23471642 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23471642/.

Carey EJ, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Lancet. 2015;386(10003):1565-1575. PMID: 26364546 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26364546/.

Carrion AF, Martin P. Liver transplantation. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 97.

Garcia-Tsao G. Cirrhosis and its sequelae. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 144.

Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65(1):310-335. PMID: 27786365 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27786365/.

Ge PS, Runyon BA. Treatment of patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):767-777. PMID: 27557303 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27557303/.

Kamath PS, Shah VH. Overview of cirrhosis. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 74.

Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144-1165. PMID: 24716201 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24716201/.

Mehta SS, Fallon MB. Hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and other systemic complications of liver disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 94.

Pavlov CS, Casazza G, Semenistaia M, et al. Ultrasonography for diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis in people with alcoholic liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD011602. PMID: 26934429 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26934429/.

Runyon BA; AASLD. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Practice Guideline management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis 2012. Hepatology. 2013;57(4):1651-1653. PMID: 23463403 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23463403/.

Shah VH, Kamath PS. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 92.

Smith A, Baumgartner K, Bositis C. Cirrhosis: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(12):759-770. PMID: 31845776 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31845776/.

Sola E, Gines P. Ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 93.

Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J, Burroughs AK. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;383(9930):1749-1761. PMID: 24480518 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24480518/.

|

Review Date:

6/26/2021 Reviewed By: Michael M. Phillips, MD, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |