Scleroderma - InDepth

Highlights

Overview

- Scleroderma is an uncommon, complex, autoimmune disease. The body's immune system attacks its own tissues. It affects the skin by causing hardened tissue or ulcers and may harm the internal organs.

- Doctors have made progress developing treatments to reduce symptoms and prolong life, but there is no cure.

- There are two major forms of the disease. Systemic scleroderma is a serious condition, while localized scleroderma carries a good prognosis and normal lifespan. In children, localized scleroderma is three times more common than the systemic form of the disease.

- The cause and course of the disease is unclear, and more research is needed to assess treatment options.

- Many studies on scleroderma show some promise, but small sample sizes make it difficult to draw strong conclusions about treatment benefits.

Treatment

Treatment involves a combination approach to treat the immune response, improve circulation, and stop the progression of skin symptoms. Several medications and therapies are in the very early phases of study for scleroderma. These agents show some promise, but additional study is needed to define their use.

- Bosentan is currently under study in the US for systemic scleroderma. It is already approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Several studies have demonstrated a reduction of new skin ulcers and accelerated healing of nondigital ulcers for certain scleroderma patients after taking Bosentan. The drug was approved in Europe in 2007 for the treatment of skin ulcers related to scleroderma.

- Non-myeloablative autologous hemopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) shows some promise in treating scleroderma. Longer follow-up and further study is needed to learn which people would most benefit, as well as to further evaluate its safety.

- Some drugs, such as rituximab (Rituxan), mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept), and imatinib mesylate (Gleevac), used to treat certain autoimmune diseases and cancers may play a role in treating scleroderma. However, larger scale, randomized, multi-center studies are necessary to determine whether they are beneficial.

Introduction

The name scleroderma comes from the Greek words skleros, which means hard, and derma, which means skin. The disease is categorized as a rheumatologic disorder because it affects the connective tissues in the body. It is rare, with an annual incidence of 18 to 20 new cases per million people and is more common in women.

Scleroderma is marked by the following:

- Damage to the cells lining the walls of small arteries

- An abnormal build-up of tough scar-like tissue in the skin

People with scleroderma may develop either a localized or a systemic (body-wide) form of the disease.

Localized Scleroderma

Localized scleroderma usually affects only the skin on the hands and face. Its progression is very slow, and it rarely, if ever, spreads throughout the body (becomes systemic) or causes serious complications. There are two main forms of localized scleroderma: morphea and linear scleroderma.

Morphea Scleroderma

In morphea scleroderma, patches of hard skin form and can last for years. Eventually, however, they may improve or even disappear. There is less than a 1% chance that this disorder will progress to systemic scleroderma.

Linear Scleroderma

Linear scleroderma causes bands of hard skin across the face or on a single arm or leg. Linear scleroderma may also involve muscle or bone. Rarely, if this type of scleroderma affects children or young adults, it may interfere with growth and cause severe deformities in the arms and legs.

Systemic Scleroderma

Systemic scleroderma is also called systemic sclerosis. This form of the disease may affect the organs of the body, large areas of the skin, or both. This form of scleroderma has two main types: limited and diffuse scleroderma. Both forms are progressive, although most often the course of the disease in both types is slow.

Limited Scleroderma (also called CREST Syndrome)

Limited scleroderma is a progressive disorder. It is classified as a systemic disease because its effects can be widespread throughout the body. It generally differs from diffuse scleroderma in the following ways:

- In most cases, the internal organs are not affected.

- The areas of the skin that are affected.

- People with limited scleroderma have a less serious course, unless they develop pulmonary hypertension (a particular danger with the CREST syndrome). Pulmonary hypertension is high blood pressure in the lungs (see the Lung Complications section).

Limited scleroderma is commonly referred to by the acronym CREST, whose letters are the first initials of characteristics that are usually found in this syndrome:

- Calcinosis. With this condition, mineral crystal deposits form under the skin, usually around the joints. Skin ulcers filled with a thick white substance may form over the deposits.

- Raynaud's phenomenon. In this syndrome, the fingers of both hands are very sensitive to cold, and they remain cold and blue-colored after exposure to low temperatures. This occurs in nearly all cases of scleroderma, both limited and diffuse. It is caused by episodic vasospasm in small blood vessels. These changes cause the vessels to narrow, and blood flow is temporarily interrupted, usually in the fingers.

- Esophageal motility dysfunction. The esophagus carries food from the mouth to the stomach. In esophageal motility dysfunction, the muscles in the esophagus become scarred by scleroderma and do not contract normally. This can cause the feeling of food being stuck, severe heartburn and other symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disorder (GERD).

- Sclerodactyly (also called acrosclerosis). This is the stiffness and tightening of the skin of the fingers, a classic symptom of scleroderma. Bone loss may occur in the fingers and toes.

- Telangiectasia. In this situation, widening of small blood vessels causes numerous flat red marks to form on the hands (on palms and around nails), face, lips, and tongue.

In general, people with limited scleroderma develop Raynaud's phenomenon long before they develop any of the other symptoms. One or more of the CREST conditions can also occur in other forms of scleroderma.

Diffuse Scleroderma

Diffuse scleroderma, the other type of systemic sclerosis, has the following characteristics:

- It can affect wide areas of the skin, connective tissue, and other organs.

- It can have a very slow course, but it also may start quickly and be accompanied by swelling of the whole hand. If it gets worse quickly early on, the condition can affect internal organs and become very severe, even life threatening.

- Diffuse scleroderma can overlap with other autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and polymyositis. In such cases, the disorder is referred to as mixed connective disease.

People with systemic scleroderma (limited or diffuse), particularly men, are at higher risk for certain types of cancers. The strongest association is with cancer of the lung, but there may be an increased risk for liver, blood, and bladder cancers, as well as non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukemia.

Risk Factors

Scleroderma is not common. It afflicts about 300,000 Americans, about one third of people who have the systemic form of the disease. The cause of scleroderma has not been determined, and there are few specific risk factors. The incidence tends to be higher in certain groups, however.

Age

Systemic scleroderma usually develops between the ages of 35 and 55. It is extremely rare in children. Localized scleroderma is more common in children than adults, but is extremely rare even in the young age group.

Sex

The prevalence of scleroderma is about four times higher in women than men, and it is higher during child-bearing years. This may reflect different causes of the disease in these two genders. (It should be noted that pregnancy itself is NOT a risk factor for scleroderma and that women in general are more susceptible to autoimmune diseases than men.) Older males tend to have a worse prognosis.

Family History

A family history is the strongest risk factor for scleroderma, but even among family members, the risk is very low (less than 1%).

Genetics

Genetic factors appear to play a role in triggering the disease, but most cases are unlikely to be inherited. Preliminary research suggests that genes and gene to gene interactions play a role.

Ethnicity

Limited data on risk by ethnic group in the United States suggests that the risk from highest to lowest is the following: Choctaw Native Americans (highest), African Americans, Hispanics, Non-Hispanic Whites, Japanese Americans.

African Americans have a higher rate of diffuse scleroderma, lung involvement, and a worse prognosis than white people. Other studies also found lower survival rates among Japanese Americans.

Genetic factors affect population groups differently. Studies are finding that ethnic groups differ in the number of specific scleroderma-related antibodies they produce. Caucasian people, for instance, have a higher rate of anti-centromere antibodies, which are associated with limited disease, while African American people have higher rates of autoantibodies and genetic factors that are associated with a more severe condition. The condition is also more severe in Native Americans.

Environmental

Researchers are evaluating a possible association between certain occupational toxins and systemic scleroderma. Examples include silica, epoxy resins, and welding fumes. While these agents may play a role, the risk is uncertain and more research is needed.

Symptoms and Complications

Raynaud's Phenomenon

Raynaud's phenomenon is often the first sign of scleroderma. With this condition, small blood vessels constrict in the fingers, toes, ears, and sometimes even the nose.

Attacks of Raynaud's phenomenon can occur several times a day, and are often brought on or worsened by exposure to cold. Warmth relieves these attacks. In severe cases, attacks can develop regardless of the temperature. Severe cases may also cause open sores or damage to the skin and bones, if the circulation is cut off for too long.

Typically, the fingers go through three color changes (white-blue-red):

- First, they become very pale.

- As the blood flow is reduced, they turn a bluish color, usually in the top two sections of the second and third fingers.

- Finally, when blood flow returns, the fingers become red.

Tingling and pain can occur in the affected regions.

Raynaud's is very common and occurs in 3% to 5% of the general population. It is important to note that more than 80% of people with Raynaud's phenomenon do not have scleroderma, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, or other serious illnesses. This form of Raynaud's phenomenon occurs most commonly in young women. Raynaud's is more likely to be a symptom of scleroderma or some other connective tissue disease if it develops after age 30, if it is severe, and if it is accompanied by other symptoms (such as skin changes and arthritis).

Skin Changes

Course of Typical Skin Changes

The primary symptoms of scleroderma occur in the skin. They often take the following course:

- Typically, pitted scars appear first on the hands. The skin begins to thicken and harden on the hands, feet, and face. The fingers may swell. This condition is called sclerodactyly or acrosclerosis. People with diffuse scleroderma may have swelling of the whole hand before the skin significantly thickens.

- Thickened or hardened patches may also develop on other areas of the body. (Their appearance on the trunk and near the elbows or knees tends to be a sign of a more severe condition.)

- For the first 2 or 3 years, the skin continues to thicken and feel puffy.

- This process then stops, and can even get better. The skin may soften.

- As the disease progresses further, however, the skin loses its ability to stretch, and becomes shiny as it tightens across the underlying bone, particularly in the fingers, toes, and around the mouth.

- Eventually, in severe cases, the fingers may lose the ability to move freely, and can be difficult to bend. The hands and feet may curl from the tightness of the skin. It may be difficult to open the mouth widely.

Other Skin Changes

The following skin symptoms may also occur:

- Flat red marks, known as telangiectasis, may appear in various locations, usually the face, palms, lips, or the inside of the mouth.

- In calcinosis, small white lumps form beneath the skin, sometimes oozing a white substance that looks like toothpaste. Calcinosis can lead to infections.

- Small blood vessels at the base of the fingernails may be severely narrowed in some places, and may widen in other places. This is an indication that internal organs might be involved.

- The entire surface of the skin may get darker over time, and contain patches of abnormally pale skin. This is referred to as the salt and pepper sign.

- Hair loss may occur.

- About 1% of people have Sjögren syndrome, a group of symptoms that include dry eyes and dry mucus membranes (such as those in the mouth).

- Inside the mouth, scleroderma can also cause changes that impair gum healing.

Bone and Muscle Symptoms

Changes in bones, joints, and muscles can cause the following symptoms:

- Mild arthritis. The condition is usually distributed equally on both sides of the body.

- Bone loss in the fingers. The destruction is not as severe as it is in rheumatoid arthritis, although the fingers may shorten over time.

- Trouble bending the fingers, if the disease has affected the tendons and joints.

- Muscle weakness may occur, especially near the shoulder and hip.

Digestive Tract Symptoms and Complications

Complications in the Upper Digestive Tract:

- Esophageal motility disorder develops when scarring in the muscles of the esophagus causes them to lose the ability to contract normally, resulting in trouble swallowing, heartburn, and gastroesophageal reflux (also known as GERD). Some experts believe that people with severe GERD may aspirate (breathe in) tiny amounts of stomach acid, which in turn may be a major cause of lung scarring.

- About 80% of people also experience impaired stomach activity. A delay in stomach emptying is very common.

- Some people develop "watermelon stomach" (medically referred to as CAVE syndrome), in which the stomach develops red-streaked areas from widened blood vessels. This causes a slow bleeding that can lead to anemia (low red blood cell counts) over time.

- There may be a higher risk for stomach cancer.

- Problems with movement of the food (motility) through the intestines also develop. This can lead to food being stuck in the esophagus and regurgitation. People may experience an increase in bacteria levels in their intestines as a result, and have trouble absorbing nutrients from foods through their intestines.

Complications in the Lower Digestive Tract

Complications in the lower digestive tract are uncommon. If they do occur, they can include the following:

- Scarring can cause blockages and constipation. In rare cases, constipation can become so severe that the bowel develops holes or tears, conditions that can be life threatening.

- Scarring can also interfere with the absorption of fats in the intestines. This can lead to an increase in the number of bacteria in the lower intestines, which can cause watery diarrhea.

- Fecal incontinence (the inability to control bowel movements) may be more common than studies indicate, because patients are reluctant to report it.

- Diverticular ulcerations, megacolon, and rectal prolapses can also occur.

Digestive complications can put people with scleroderma at risk for malnutrition and/or incomplete absorption of nutrients. Many people, however, have few or even no lower gastrointestinal symptoms.

Lung Symptoms and Complications

In severe cases, the lungs may be affected, causing shortness of breath or difficulty in taking deep breaths. Shortness of breath may be a symptom of pulmonary hypertension, an uncommon but life-threatening complication of systemic scleroderma.

Lung problems are usually the most serious complications of systemic scleroderma. They are now the leading cause of death in people with scleroderma. Two major lung conditions associated with scleroderma, pulmonary fibrosis, and pulmonary hypertension, can occur either together or independently.

Interstitial Lung Disease and Pulmonary Fibrosis

Scleroderma involving the lung causes lung inflammation (interstitial lung disease) and scarring (pulmonary fibrosis). Pulmonary fibrosis occurs in about 20% of people with scleroderma with limited skin disease and 80% of people with scleroderma with more severe disease (diffuse cutaneous), although its progression is very slow and people have a wide range of symptoms:

- Some people may not have any symptoms.

- When pulmonary fibrosis progresses, people develop a dry cough, shortness of breath, and reduced ability to exercise.

- Severe pulmonary fibrosis occurs in about 16% of people with diffuse scleroderma. About half of these people experience the most profound changes within the first 3 years of diagnosis. In such cases, lung function worsens rapidly over that period, and then the progression slows down.

Pulmonary fibrosis also places the person at higher risk for lung cancer.

Pulmonary fibrosis is strongly associated with the presence of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). It is thought that lung involvement may be due to severe dysfunction in the esophagus, which causes people to aspirate tiny amounts of stomach acid.

The most important indication of future worsening in the lungs appears to be inflammation in the small airways (alveolitis). Doctors detect alveolitis by using a lung test called bronchoalveolar lavage.

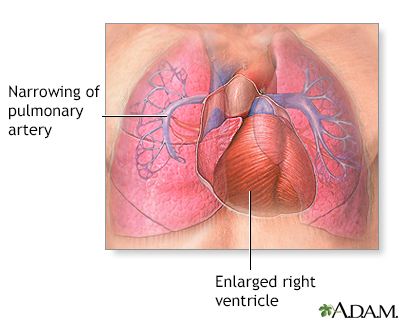

Pulmonary hypertension is the narrowing of the pulmonary arteries in the lung. The narrowing of the arteries creates resistance and increases the workload of the heart. The heart becomes enlarged from pumping blood against the resistance. Some symptoms include chest pain, weakness, shortness of breath, and fatigue. The goal of treatment is to control the symptoms, although the disease usually develops into heart failure.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension is caused by the narrowing of the pulmonary arteries in the lung. The narrowing of the arteries creates resistance to blood flow, increases the pressure in these arteries, and increases the workload of the heart. The heart becomes enlarged from pumping blood against this resistance. Symptoms of pulmonary hypertension include shortness of breath, chest pain, weakness, and fatigue. Shortness of breath, the primary symptom of pulmonary hypertension, worsens over time. Chest pain and ankle swelling are less common signs. The goal of treatment is to control the symptoms, although the disease eventually produces heart failure, usually after about 10 years.

Pulmonary hypertension can develop in one of two ways:

- As a complication of pulmonary fibrosis.

- As a direct outcome of the scleroderma process itself. In this case, it is most likely to develop in people with limited scleroderma after many years.

Kidney Symptoms and Complications

Signs of kidney problems, such as increased amounts of protein in the urine and high blood pressure (hypertension), are common in scleroderma (but somewhat less common in children). As with pulmonary hypertension, the degree of severity depends on whether the kidney problems are acute or chronic.

Slow Progression

The typical course of kidney involvement in scleroderma is a slow progression that may produce some damage but does not usually lead to kidney failure.

Renal Crisis

The most serious kidney complication in scleroderma is renal crisis. It is a rare event that occurs in a small number of patients with diffuse scleroderma, most often early in the course of the disease. This syndrome includes a life-threatening condition called malignant hypertension, a sudden increase in blood pressure that can cause rapid kidney failure. This condition may be fatal. However, if the condition is successfully treated, it rarely recurs.

Until recently, renal crisis was the most common cause of death in scleroderma. Aggressive treatment with drugs that lower blood pressure, particularly those known as ACE inhibitors, is proving to be successful in reducing this risk of kidney damage and can reverse damage at times.

Heart Symptoms and Complications

Many people with even limited scleroderma have some sort of functional heart problem, although severe complications are uncommon and occur in only about 15% of people with diffuse scleroderma. As with other serious organ complications, they are more likely to occur within 3 years after the disease begins. Research has shown that patients with systemic scleroderma have a higher risk for atherosclerosis than healthy individuals.

Fibrosis of the Heart

The most direct effect of scleroderma on the heart is fibrosis (scarring). It may be very mild, or it can cause pain, low blood pressure, or other complications. By damaging muscle tissue, the scarring increases the risk for heart rhythm problems, problems in electrical conduction, and heart failure. The membrane around the heart can become inflamed, causing a condition called pericarditis.

Pulmonary hypertension and hypertension associated with kidney problems in scleroderma can also affect the heart. Long standing pulmonary hypertension can lead to heart failure.

Other Symptoms and Complications

Other complications of scleroderma may include the following:

- People with CREST may be at increased risk for biliary cirrhosis, an inflammatory autoimmune disorder of the liver.

- Nerve damage may occur in the extremities (legs, feet, arms, fingers, and toes), causing numbness and pain. This damage can progressively worsen and lead to severe open sores (ulcerations), particularly in the hands. The feet are less often affected, but when they are, the disease tends to affect the joints and cause pain.

- Bone loss (osteoporosis) can occur because of impaired blood flow.

- About 10% to 15% of people with scleroderma develop underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism).

- Erectile dysfunction, usually due to scarring of the penis, may be one of the first complications of the disease in men.

- Systemic scleroderma does not generally affect fertility in women. Pregnant women with scleroderma, however, have a slightly increased risk for premature birth and low-birth-weight babies. Although they can carry a baby to term, because complications such as kidney crisis can occur with the disease, pregnant women with scleroderma need to be monitored closely in a high-risk obstetric facility.

- More than one half of people with scleroderma are likely to experience significant depression. Researchers say it may be beneficial for people with scleroderma to be routinely screened for depression.

- About 30% of people with scleroderma are estimated to be at medium to high risk for malnutrition due to swallowing problems and other digestive complications.

- People with scleroderma may have a slightly increased risk for malignancy compared to the general population. Some specific cancers have been observed more frequently in people with scleroderma, including lung, esophageal, and lymphoma.

Causes

Most likely this disease is caused by several inherited (genetic) abnormalities, which are triggered by environmental factors.

Inflammatory Response and Autoimmunity

The disease process leading to scleroderma appears to occur as an autoimmune response, in which an abnormal immune system attacks the body itself. In scleroderma, this response produces swelling (inflammation) and too much production of collagen. Collagen is the tough protein that helps build connective tissues such as tendons, bones, and ligaments. Collagen also helps scar tissue form. When normal tissue from skin, lungs, the esophagus, blood vessels, and other organs is replaced by this type of abnormal tissue, none of these body parts work as well, and many of the symptoms previously described occur.

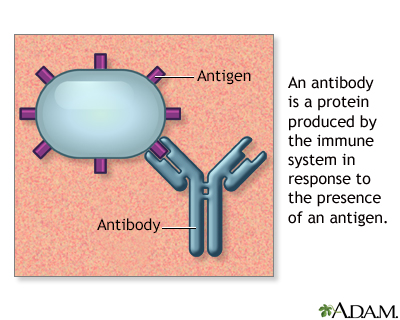

Antigens are large molecules (usually proteins) on the surface of many cells, both human cells, and cells of viruses, fungi, bacteria, and some non-living substances such as toxins, chemicals, drugs, and foreign particles. When the immune system recognizes an antigen as being foreign (not part of the human body), it starts offensive and defensive actions against them by producing antibodies and other chemicals such as cytokines that destroy any cells in the area.

Much of this activity is directed by white blood cells known as T cells, which are subdivided into killer T cells and helper T cells (TH cells).

The actions of the helper T cells are of special interest in scleroderma. For some unknown reason, the T cells become overactive in scleroderma and mistake the body's own collagen for a foreign antigen. This triggers a series of immune responses to destroy the collagen. When the body creates antibodies against itself in this way, it is called an autoimmune response. While this abnormal immune activation is thought to be active early in disease progression, the failure of immunosuppressive drugs to control the disease suggests that this activation may change over time and be less important later in the disease.

Genetics

Research has demonstrated that systemic sclerosis is a polygenic (involving more than one gene) autoimmune (involving the immune system response) disease. Several genes and gene-gene interactions have been identified as playing a role in systemic sclerosis. Many of these same genes are linked to related diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus.

The genes are involved in the regulation of the immune system.

Triggering the Immune Response

It is still not clear why the immune system responds abnormally in people with scleroderma. Some experts believe that environmental factors, such as a virus or a chemical, may trigger the response in individuals with a genetic vulnerability.

Chemicals

Occupational exposure to certain chemicals can cause blood vessel constriction and attacks of Raynaud's phenomenon. Despite the fact that women are at higher overall risk for scleroderma, among people who are exposed to solvents at work, men face a higher risk for the disease. However, no specific work-related factors have been proven to cause the disorder.

It is nearly impossible to determine whether specific chemicals may actually cause systemic scleroderma, primarily because few people develop the disease, even though many people are exposed to such chemicals. In addition, research has been unable to consistently repeat studies that have reported links with chemicals.

Studies have found, however, that certain industrial toxins are significantly associated with severe lung problems in people with scleroderma. The toxins most likely to be associated with severe disease include epoxy resins, pesticides, white spirit, organic solvents, and silica mixed with welding fumes.

Radiation

Radiation therapy has been reported to cause local patches of scleroderma (morphea) or worsen preexisting scleroderma in people. In some cases, scleroderma may occur years after radiation treatments.

Diagnosis

There are no specific tests for scleroderma. The doctor may suspect scleroderma after taking a history of the symptoms and performing a physical examination. A scoring system, such as the modified Rodnan skin score, is often used to assess the severity of skin disease. As part of this examination, the doctor does the following:

- Checks the skin for thickened and hardened areas. The major signs of scleroderma are hardening and thickening of the skin in any areas on the fingers and toes.

- Presses affected tendons and joints to detect crackling or grating sensations, which can indicate changes related to scleroderma beneath the skin.

- Examines the fingernails underneath a microscope. The doctor may find dilative changes in capillaries that are characteristic of scleroderma or mixed connective tissue disease.

- To better assess disease status over time, objective measures, such as ultrasound, computerized skin score, laser technology and scoring systems are under study.

Serology or Antibody Testing

Tests may be done to detect immune factors called antinuclear antibodies (ANAs). Detecting specific types of ANAs may help diagnose scleroderma. Autoantibody subtypes found in systemic sclerosis include the following:

- Rheumatoid factor, anti-single-stranded DNA, and antihistone antibodies are autoantibodies associated with scleroderma, but they are also common in other autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Some ANAs attack RNA or DNA, the genetic material in cells.

- Anti-RNA polymerase III, anti-topoisomerase I (TOPO, also called anti-DNA topo 1) and anti-centromere antibodies (ACA) are also autoantibodies. Most people with systemic scleroderma (but not localized scleroderma) have one or more of these autoantibodies. They do not appear at the same time, and seem related to different phases of the disease process. For example, anti-DNA topo 1 often occurs with diffuse skin scleroderma and lung complications (and carries the worst prognosis). Anti-centromere antibodies usually occur with a less severe form of the disease.

- Higher-than-normal levels of autoantibodies to fibrillin 1, a protein found in muscle and other connective tissues, are more common in people with both systemic and localized scleroderma. This autoantibody in localized scleroderma is more common in some ethnic groups (such as Japanese and Native Americans) than in others (White people). It is not found in other autoimmune diseases.

These antibodies are also found in other rheumatologic disorders, so detecting them does not necessarily prove that a person has scleroderma. At the same time, studies have found that specific antibodies are associated with specific aspects of the disease. Therefore, identifying their presence could help diagnose, treat, and monitor people with scleroderma. Here are a few examples:

- Anti-U1-RNP and anti U3-RNP are associated with muscle inflammation.

- ACA is commonly associated with pulmonary hypertension and vascular disease.

- TOPO is associated with pulmonary fibrosis.

- RNA Polymerase III (Pol 3) is rarely linked to severe interstitial fibrosis, although this autoantibody is strongly present in people with kidney crisis.

- People with diffuse scleroderma who have Pol 3 have the best survival rates.

Diagnosing Systemic Complications

Diagnosing Lung Complications

Changes in the lungs may occur early in scleroderma lung disease, and prompt treatment is very important to prevent complications. For this reason, once a diagnosis is made, the doctor will check for lung changes in the following ways:

- Listen to the lungs through a stethoscope. Rales, a crackling sound at the base of the lungs as the person breathes in, is a sign of pulmonary fibrosis, even if breath function is normal.

- Perform respiratory function tests to determine lung capacity.

- Take a chest x-ray (however, x-rays do not always find lung disease, especially in children).

- Have people inhale nitric oxide to test the ability of blood vessels to open.

- Perform more extensive tests, such as high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scans and bronchoalveolar lavage, if there is a suspicion of severe lung scarring.

Newer tests showing promise in diagnosing lung complications include:

- The induced sputum test, which looks at cells taken from coughed-up phlegm

- A test that uses an inhaled chemical called 99mTC-DTPA to detect lung damage

Diagnosing Heart Complications

People with suspected heart complications should have the following tests:

- Electrocardiography (ECG). A test of the heart's electrical activity.

- Echocardiography. A look at the beating heart through the use of sound waves.

- Radionucleotide ventriculography. An evaluation of the working heart using a radioactive dye.

Advanced imaging techniques, which provide a more detailed picture of the heart, may also be useful to determine the extent of heart complications in scleroderma patients.

Diagnosing Pulmonary Hypertension

Echocardiography is a noninvasive imaging technique for detecting pulmonary hypertension. (Noninvasive means that neither materials nor equipment are put into the body.) To confirm the diagnosis, doctors sometimes use an invasive procedure called right-heart catheterization. Right-heart catheterization involves the passage of a catheter (a thin flexible tube) into the right side of the heart to get diagnostic information about the heart.

Diagnosing Gastrointestinal (Digestive) Complications

Digestive issues are common among people with scleroderma and malabsorption can be a problem. Endoscopy may help identify specific gastrointestinal disorders in people with severe pain. Endoscopy is an invasive procedure in which a tube is inserted down the esophagus. The tube contains a small camera and other instruments. Another diagnostic test is manometry, which measures the pressure that the muscles in the esophagus apply. Hydrogen breath tests and measuring fat soluble vitamins can help identify malabsorption.

Electrogastrography (EGG) measures the electrical activity in muscles in the stomach, and may be an effective method for detecting stomach problems.

Diagnosing problems in the growth of blood vessels

Capillaroscopy is the microscopic examination of blood vessels under the skin. It is now considered a useful tool for identifying problems with the growth of blood vessels, because more than 95% of people will have some capillary abnormalities. Such problems can show the severity and progression of scleroderma. In a technique called nailfold capillaroscopy, the doctor places a drop of oil on the nailfold (the skin at the base of the fingernails), and then looks at the nailfold under a microscope for signs of changes in the capillaries. These changes may indicate a connective tissue disease such as scleroderma.

Ruling out Other Conditions

Other Autoimmune and Connective Tissue Disorders

Several other autoimmune conditions that affect connective tissue can strongly resemble, or occur together with, scleroderma. They include the following:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Polymyositis

Symptoms of such diseases may also include fever, arthritis, muscle aches, rash, and lung and heart problems.

Eosinophilic Fasciitis

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a muscle disorder that is known to occur after intense hard work. It can cause symptoms similar to scleroderma, including pain, swelling, and tenderness in the hands and feet, as well as skin thickening with a dimpled appearance. The disorder can be ruled out with blood tests. Eosinophils are usually very high in blood tests.

Other causes of Raynaud's phenomenon

Although Raynaud's phenomenon occurs in most people with scleroderma, most of the time Raynaud's phenomenon by itself is not associated with more serious conditions. Following are other problems that might accompany or cause Raynaud's phenomenon:

- Other autoimmune connective tissue diseases

- Diabetes (people with diabetes may develop Raynaud's phenomenon and other scleroderma-like symptoms)

- Certain drugs, including bleomycin, ergot derivatives (used for migraines), and methysergide

- Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (a very rare condition that may have skin changes similar to CREST syndrome)

- Repetitive stress injuries (particularly from vibrating tools)

- Hypothyroidism

Prognosis

At this time there is no cure for scleroderma, and no treatment to change its course, but outlook varies widely. Many people, even those with systemic scleroderma, can expect a normal lifespan.

General Outlook of Localized Scleroderma

Localized scleroderma nearly always carries a good prognosis and a normal lifespan. Even localized scleroderma, however, can cause some severe effects in children, including impaired growth, limb imbalance, and problems with flexing and bending muscles. Five-year survival among these people has remained steady at around 90%.

General Outlook of Systemic Scleroderma

The outlook for people with systemic scleroderma has improved over the past 40 years, with ten-year survival rates around 60% to 70%. Survival rates in children are generally better than those for adults.

The causes of death related to systemic scleroderma also have changed. The proportion of deaths from kidney crises has dropped significantly, while the proportion of deaths from pulmonary fibrosis has increased. Today, heart and lung complications account for the majority of scleroderma-related deaths.

- Limited Scleroderma. People with limited CREST scleroderma can usually expect a favorable outlook and normal lifespan if the disease affects only the hands and face. The course of this type of scleroderma still tends to be slowly progressive and, in some cases, may affect internal organs.

- Diffuse Scleroderma. The severity of diffuse scleroderma varies widely, and it is very difficult to predict its course. Breathing problems appear to be the strongest predictor of disability related to the disease. It generally follows one of two paths. If it is acute or rapidly progressing, it may be a life-threatening condition that affects internal organs. The most critical period for rapid progression is usually within the first 2 to 5 years of the start of the disease. In the absence of rapid progression, or if the person survives the initial acute progression, the disease tends to progress very slowly. The more severe the condition of the skin is at the start of the disease, the poorer the survival rates.

Many people with systemic scleroderma experience a plateau in which the condition stabilizes. This plateau is followed by a period of improvement and skin softening. No one knows why this occurs, and it can happen regardless of treatment. In one study, people with systemic scleroderma who experienced such improvements also had better survival rates (80% at 10 years) than those whose skin did not improve (60% 10-year survival rate).

Impact on Quality of Life

The many complications of scleroderma can have a major impact on a person's sense of well-being. People are greatly concerned about changes in their appearance, particularly those changes caused by tightening of the facial skin. Depression has great impact, along with pain, on reducing a person's ability to function socially.

Treatment

In general, patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc) are treated with organ-based symptomatic therapy. Patients with diffuse skin involvement and/or severe inflammatory organ involvement are usually treated with systemic immunosuppressive therapy. This includes:

- Patients with diffuse skin involvement that is severe or progressive

- Patients with interstitial lung disease

- Patients with myocarditis

- Patients with severe inflammatory myopathy and/or arthritis

Immunomodulation/immunosuppressive treatment

The aim of immunosuppressive therapy is to reduce progression or severity of SSc complications. Treatment should be started as early as possible in the disease course to slow disease progression before further damage occurs. Unfortunately, the benefit of such therapies is often limited and there is no standard therapy.

A number of immunotherapies are being used in SSc with varying degrees of efficacy:

- Cyclophosphamide

- Glucocorticoids

- Cyclosporine

- Methotrexate

- Other immunosuppressive agents

- Autologous stem cell transplantation

Fibrotic lesions may occur with frightening speed in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc). This fact, alone, would justify starting an antifibrotic drug as soon as possible in patients with diffuse disease and possibly administering such a drug concurrently with an immunosuppressive agent.

Antifibrotic drugs include:

- D-penicillamine

- Interferons

- Colchicine

- Iloprost

- Relaxin

- Anticytokine therapy, targeted therapy against certain factors

Investigational approaches

- Imatinib

- Rituximab

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Immune tolerance induction

- Other biologic agents targeting IL-6 (tocilizumab) may benefit skin and other outcomes in SSc

Scleroderma treatments vary depending on several variables:

- Is it local or systemic, and if systemic, is it limited or diffuse?

- If the disease is systemic, what organs, if any, are involved?

Although there is still no definitive treatment for the underlying process of scleroderma, specific drugs and treatments help combat the various mechanisms and consequences of the disease.

- Some medications keep blood vessels open (prostacyclins, endothelin receptor antagonists, ACE inhibitors, phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, and others) and are used to treat Raynaud's phenomenon, heart and kidney problems, and pulmonary hypertension.

- Other drugs reduce inflammation and block damaging immune factors. These treatments, which include cyclophosphamide, penicillamine, and bone marrow transplantation, may be helpful for improving skin thickness and reducing scarring, even in the lungs.

- Doctors use other treatments for specific complications, such as proton pump inhibitors and pro-kinetic agents for gastrointestinal problems, or light treatments for skin thickening.

- Various investigative approaches exist, including stem-cell transplants and biologic drugs.

People should receive treatments for specific complications as early as possible in the course of the disease, to reduce progression before irreversible hardening of tissues occurs.

There is no cure for scleroderma. Many drugs that are useful for other autoimmune inflammatory disorders have not proven to be very effective for scleroderma. Experimental work is ongoing to develop procedures or to find drugs that can treat the underlying processes that cause damage. Developing effective treatments for scleroderma is very problematic, however, for the following reasons:

- The course of scleroderma is hard to predict, making it one of the most difficult rheumatic diseases to treat. It also makes drug development complicated.

- The disease, when advanced, affects many organs. Designing treatment strategies that will improve symptoms in some organs without affecting other organs is very difficult.

- The disease is so uncommon that there are few people available for clinical trials. Studies, then, are very small, sometimes having only four or five people. It is very difficult to design studies of this size that can provide strong evidence on treatment effects. Drugs that seem promising on small groups of people often fail to show effectiveness on larger groups.

Treating the Whole Person

The disease can evolve slowly over time with few symptoms, or progress rapidly and become very severe. The person, then, must live with considerable uncertainty and emotional stress. Support associations, non-medical aids to help relieve symptoms (such as protection from trauma and cold), and other lifestyle measures can be extremely important and helpful.

Medications

Calcium-channel blockers are the standard drugs to dilate the blood vessels, and may be used for pulmonary artery hypertension and Raynaud's phenomenon. Short-release or sustained-release nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia) is the gold standard. Other drugs used include diltiazem (Cardizem, Dilacor), and dihydropyridine medications (felodipine, amlodipine, and isradipine). Side effects vary among different medications and may include:

- Fluid buildup in the feet

- Constipation

- Fatigue

- Gingivitis

- Headache

- Erectile dysfunction

- Facial flushing

- Allergic symptoms

Certain calcium channel blockers should not be taken with grapefruit juice, as it appears to boost the effects of these drugs. [The medications listed below are also discussed under many of the sections covering treating complications of scleroderma.]

ACE Inhibitors and Angiotensin II Receptors

The most effective approach at this time for preventing kidney (renal) crises is to start aggressive blood pressure-lowering treatment before blood tests show kidney damage has occurred.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors

Many medications are available for controlling blood pressure, but ACE inhibitors appear to be the most effective for people with scleroderma because of their protective actions in the kidney. These drugs are also used to treat people with evidence of kidney damage, whether or not they have high blood pressure. ACE inhibitors include medications like captopril (Capoten), enalapril (Vasotec), quinapril (Accupril), and lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril). Side effects are uncommon but may include an irritating cough, large drops in blood pressure, and allergic reactions.

Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists (losartan, candesartan cilexetil, and valsartan) have benefits similar to ACE inhibitors and may have fewer or less severe side effects, including coughing. They may also have positive effects on blood vessels. Small studies showing improvement in Raynaud's phenomenon warrant further research.

Nitrates

Nitrates relax smooth muscles and open arteries, and are therefore sometimes used for the short-term management of Raynaud's phenomenon. They are available in topical and oral (by mouth) forms. Side effects of nitrates include headaches, dizziness, nausea, blurred vision, fast heartbeat, and sweating. Lying down with the legs elevated can relieve low blood pressure and dizziness. Alcohol, beta blockers, calcium-channel blockers, and certain antidepressants can significantly worsen these side effects. People taking nitrates cannot use PDE5 inhibitors (see below). Withdrawal from nitrates should be gradual. Some severe reactions have occurred when people have stopped taking these drugs too quickly.

Prostacyclin analogs

Synthetic analogs of prostacyclin (also called prostaglandin I2 or PGI2) open blood vessels and also have anti-blood-clotting properties. One or all of these drugs is used to treat pulmonary artery hypertension and Raynaud's phenomenon. Several prostacyclin analogs are being used for scleroderma, although none have been approved specifically for the condition. Promising prostacyclin analogs or similar prostaglandin drugs include iloprost (Ventavis), alprostadil (prostaglandin E1), epoprostenol (Flolan), treprostinil (Remodulin), and selexipag (Uptravi).

Endothelin Receptor Antagonists

Bosentan (Tracleer), macitentan (Opsumit), and Ambrisentan (Letaris) are drugs taken by mouth. They are called endothelin receptor antagonists. They block the effects of endothelin, a powerful molecule that causes blood vessels to narrow, and is implicated in the circulatory and skin conditions related to scleroderma.

These drugs may be used for preventing finger ulcers and improving hand function, however they are FDA-approved only for pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) at this time.

PDE5 Inhibitors

A class of drugs called PDE5 inhibitors, which includes sildenafil (Revatio) and tadalafil (Adcirca) have been approved for pulmonary hypertension. Sold under different names (Viagra, Cialis), these drugs are also used to treat erectile dysfunction. PDE5 inhibitors are being studied for their role in treating Raynaud's phenomenon and the healing of existing digital ulcers.

Treatments that Affect the Immune System

One major approach to scleroderma is to use treatments that suppress the immune system, and therefore reduce the activity of the harmful processes that lead to scleroderma. Such treatments are used effectively in other autoimmune diseases. Their effectiveness in scleroderma varies, depending on the location and severity of the disease process.

Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)

Cyclophosphamide is the most important immunosuppressant currently used for scleroderma. This drug can be taken through a vein (intravenous) or by mouth. It blocks some of the destructive actions of scleroderma in the lungs. Intravenous cyclophosphamide can be life-saving for people with pneumonia caused by interstitial lung disease. Side effects of this drug include hair loss, infection, and bleeding into the urinary tract, and an increase in the risk for cancer. Cyclophosphamide therapy is sometimes followed by maintenance therapy with immunotherapy agents such as azathioprine (AZA) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). To date, no other immunosuppressive drugs have shown significant benefit for scleroderma.

Other drugs used to suppress the immune system may be useful in specific cases. They include D-penicillamine (which may be useful for skin symptoms), methotrexate (Rheumatrex), sirolimus (rapamycin), antithymocyte globulin (ATG), corticosteroids, cyclosporine A, and chlorambucil (Leukeran). All of these drugs have potentially severe side effects.

Biologic drugs, such as rituximab (Rituxan), tocilizumab (Actemra), and imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), that are used to treat certain cancers and illnesses that involve an overactive immune system may play a role in treating scleroderma. Small research trials have shown a benefit with the use of these drugs for lung and skin problems in those with scleroderma. To date, these medicines are not approved for the treatment of scleroderma. Larger scale, randomized, multi-center studies are necessary to determine whether they can play a standard role in treatment.

Other Treatments

Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation

Researchers are investigating a possible benefit of transplanting the patient's own stem cells (an autologous transplant). The transplant procedures introduce normal white blood cells that replace the abnormal autoimmune cells. Randomized controlled trials found stem cell transplants superior to monthly cyclophosphamide for the therapy of severe systemic scleroderma. Additional studies and longer follow-up is needed to confirm these results.

Although the risk for death from having a transplant is now less than 10%, the procedure has serious side effects. Experts suggest that the best candidates for transplant are those with rapidly progressive SSc at risk for organ failure. In view of the high risk for treatment-related side effects and for early treatment-related mortality, careful selection of patients with SSc for this kind of treatment and the experience of the medical team are of key importance. In general, people with advanced scleroderma would not be the best candidates because the risks for the procedure would outweigh the risks from the disease.

Herbs and Supplements

Because of the difficulty in treating scleroderma, many people are tempted to try high-dose supplements or other alternative treatments. Some natural treatments have been evaluated for the treatment of scleroderma, including para-aminobenzoic acid, vitamin E, evening primrose oil, and an avocado/soybean extract. However, these treatments have not been proven effective, and using alternative remedies can be dangerous.

There is almost no published research on the use of herbal remedies for people with scleroderma. Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been numerous reported cases of serious and even deadly side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Treatment for Raynaud's Phenomenon

The following are some lifestyle tips for managing Raynaud's phenomenon:

- Keeping warm is the primary goal for preventing the onset of Raynaud's phenomenon. Air-conditioning and exposure to refrigeration can trigger this syndrome. If people go out in cold weather, they should dress warmly with many layers. Wearing a hat is essential.

- Living in a warm climate may help relieve symptoms, although a recent study found that weather changes themselves had little effect on the disorder.

- Exercise is helpful for maintaining a sense of well-being, keeping warm, and sustaining skin flexibility. However, people with Raynaud's phenomenon may want to avoid exercising outdoors in cold weather.

- Quitting smoking is, of course, essential for anyone, but it is critical for people with scleroderma.

- Learning relaxation and anti-stress techniques might help reduce some triggers of Raynaud's phenomenon.

- Using moisturizers and antibiotic ointments may be helpful for keeping skin flexible and preventing infections in the fingers.

- Avoiding medications such as nonselective beta blockers (for example, propranolol), certain common cold preparations, and narcotics can reduce the risk of aggravating Raynaud's phenomenon.

Medications Used in the Treatment of Raynaud's Phenomenon

Vasodilators

Vasodilators open blood vessels and so are important for Raynaud's phenomenon.

Calcium-channel blockers

Calcium channel blockers, including diltiazem (Cardizem, Dilacor) and nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia), are the standard vasodilating drugs used for Raynaud's phenomenon. Nifedipine is the best studied of these drugs, but there are also newer dihydropyridines, including felodipine, amlodipine, and isradipine.

Nitrates

Available in topical or oral forms, are vasodilators that are also used for Raynaud's phenomenon, and for short-term relief.

Prostacyclin analogs

Iloprost and other prostacyclin analogs are proving to be effective agents for Raynaud's phenomenon. Small but well done studies seem to show these drugs to be helpful for this condition, and possibly as effective as calcium channel blocker drugs such as nifedipine. Evidence shows that intravenous iloprost given at progressively increasing doses over 3-month cycles can reduce the duration and frequency of attacks. In general, these drugs are used when a patient's symptoms are severe, particularly when the doctor is considering amputating a finger.

Endothelin receptor agonists have also been shown to help with Raynaud's phenomenon.

PDE5 Inhibitors

PDE5 inhibitors, which include sildenafil (Revatio) and tadalafil (Adcirca), help improve symptoms and blood flow, and speed digital ulcer healing in people with Raynaud's phenomenon. This treatment for ulcer healing is still experimental, but it is approved for pulmonary hypertension. Longer trials are needed to confirm the role of these medications. Under different names (Viagra, Cialis), these drugs are also used to treat erectile dysfunction.

Surgical Treatments for Problems of the Hands

Sympathectomy and Hand Surgeries

Sympathectomy uses procedures that block or remove the nerve responsible for narrowing blood vessels in the hand. The result is increased blood flow in the hand.

The local anesthetics lidocaine or bupivacaine may be very effective in temporarily restoring blood flow and reducing pain.

Injection of botulinum toxin is also being investigated

For finger ulcers that will not heal and are resistant to standard treatments, sympathectomy surgery may be done.

Other Surgeries

Disabling deformity of the hand is a common feature of scleroderma. Various surgical procedures can relieve pain, prevent tissue loss, protect hand function, and improve the appearance of the hands.

Treatment for Skin Thickening

Nitroglycerin is a quick acting nitrate and is used as an ointment (Nitro-Bid, Nitrol, Nitrong, and Nitrostat) to treat hardened skin. Before applying it, remove any ointment that remains from the previous application. People using nitrates in any form cannot take PDE5 inhibitors.

Phototherapy

UVA-1 Phototherapy

Phototherapy (light therapy) is now considered by some experts to be the treatment of choice for local scleroderma. Specifically, doctors favor an approach called ultraviolet A-1 (UVA-1) radiation. This treatment produces long UVA wave lengths that do not cause sunburn and may actually repair DNA in damaged skin cells. The procedure is effective for all stages of morphea. It increases skin elasticity and in some cases, completely clears up symptoms.

UVA-1 phototherapy is quite expensive and requires a special light source not available everywhere. In addition, studies are reporting an increased risk with UVA radiation. Whether this applies to UVA-1 phototherapy is not yet clear. Nonetheless, phototherapy is still an effective and important treatment of scleroderma. It may prove to be even more beneficial when combined with certain medications, such as calcipotriene (Dovonex), a form of vitamin D3.

PUVA

An alternative phototherapy regimen called PUVA uses drugs called psoralens taken by mouth before UVA treatment. PUVA has been used for other skin diseases, including psoriasis. It may prove useful for people with early-onset diffuse scleroderma. This treatment is known to increase the risk for skin cancer.

Phototherapy with Psoralen Water Bath

Yet another procedure uses UVA light therapy after people take a bath containing a solution of psoralen 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP). This treatment is safe and well tolerated, although benefits appear to be minor and occur only in a small subset of people.

Vitamin D3 Analogs

A form of vitamin D3, calcipotriene (Dovonex), appears to help block skin cell production. This vitamin is called calcipotriol in Europe. It also has anti-inflammatory properties, and is being investigated as a rub-on treatment and oral treatment for local scleroderma. It may prove beneficial when combined with low-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy.

Immunosuppressive Agents

D-penicillamine is proving to be an effective agent for softening skin and reducing thickness. (Improvements in thickness with this drug have also been associated with improved survival.)

Methotrexate (Rheumatrex) is another commonly used drug, and may be even more effective than penicillamine.

Corticosteroids taken by mouth, such as prednisolone and prednisone, are also often used. However, prednisone may set off a renal crisis; doses should not exceed 10 mg per day and should be used for brief periods.

Rituximab (Rituxan) has been helpful in reducing skin thickening but had no benefit on lung fibrosis in a prospective trial.

Extracorporeal Photopheresis

Extracorporeal photopheresis (ECT) is a treatment which helps to destroy diseased cells. Blood is drawn for 3 to 4 hours each day for 2 days and treated with medicine and ultraviolet light, helping to destroy diseased white blood cells.

- It is approved by the FDA for the treatment of advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), and has shown skin and organ benefits in treating scleroderma.

- Guidelines developed by the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) recommend it be used as second-line or adjuvant therapy along with other treatments in early progressive disease.

Treatment for Other Complications

Pilocarpine (Salagen) has been approved for treating dry mouth in people with scleroderma and Sjögren syndrome. In one study, people with Sjögren syndrome experienced increased salivation after the first dose. People reported improvement in speaking, sleeping, and swallowing food without drinking. Side effects of this drug include sweating, increased need to urinate, chills, and flushing.

Treatment for Lung Complications

Pulmonary Fibrosis

Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), an immunosuppressive drug, may be effective for preventing lung deterioration and is an important medication for treating pulmonary fibrosis, particularly when given early in the course of the disease.

Use of this drug may improve survival in people who show early signs of lung deterioration, notably inflammation in the small lung airways (alveolitis). The drug is not recommended for people with existing stable pulmonary fibrosis and no signs of inflammation. It can also have many side effects, including hemorrhagic cystitis, bladder cancer, and infertility.

Other Treatments

Lung transplantation may offer hope for people with advanced pulmonary hypertension or interstitial fibrosis that does not respond to conservative treatments.

Nintedanib (Ofev), currently used to treat idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, was found to reduce the decline in lung function (forced vital capacity) over one year in patients with pulmonary fibrosis associated with systemic sclerosis. Nintedanib was approved by the FDA for use in adults with interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis or scleroderma.

Pulmonary Hypertension

Several types of drugs are used to treat pulmonary hypertension. Anticoagulants taken by mouth, such as warfarin (Coumadin), are a standard treatment used to prevent blood clots from forming. Diuretic treatment and supplemental oxygen are recommended for patients with fluid retention and low blood oxygen, respectively.

Vasodilators help open blood vessels and relieve pressure in arteries of the lungs. Vasodilators used to treat pulmonary hypertension fall into several different drug classes.

Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs)

Some people with pulmonary hypertension benefit from these drugs. They help relax blood vessels in the heart and lungs, and increase the supply of oxygen. However, CCBs are only appropriate for people who meet certain diagnostic criteria, including those who do not have right-sided heart failure. Long-acting nifedipine, diltiazem, or amlodipine are the preferred calcium channel blockers.

Prostacyclin analogs

Synthetic analogs of prostacyclin (PGI2), a type of prostaglandin which opens blood vessels, are now the primary agents for treating pulmonary hypertension.

- Iloprost (Ventavis) is available in inhaled and intravenous forms. Studies suggest that the inhaled form improves exercise capacity and survival in some patients with pulmonary hypertension. In addition, infusions of iloprost remain effective over long periods (up to 3 years) of use.

- Treprostinil (Remodulin) is similar to epoprostenol but is more stable. It can also be administered using a portable pump that delivers the drug under the skin. This is less expensive, cumbersome, and invasive than the delivery methods for epoprostenol.

- Epoprostenol (Flolan), which is administered intravenously, has improved exercise capacity and symptoms in both the short- and long-term in a number of people. In some people, survival is increased significantly. However, not all people respond to this drug. The implanted catheter needed to deliver the drug can also cause serious complications.

Endothelin Receptor Antagonists

Bosentan (Tracleer) was the first drug taken by mouth that was approved for pulmonary hypertension. Bosentan controls endothelin, a powerful substance that causes blood vessels to narrow. Studies have reported improved exercise capacity in patients with pulmonary hypertension after taking bosentan. Sitaxsentan and ambrisentan (Letairis) are additional drugs being studied.

PDE5 Inhibitors

Sildenafil (Revatio) was approved in 2005 as the first pill for people with early-stage pulmonary hypertension. Sildenafil is the same medication contained in the erectile dysfunction drug Viagra. However, Revatio is prescribed at a lower dosage than Viagra, and is a different color and shape than Viagra pills. A similar medication, tadalafil, is also approved for pulmonary hypertension (Adcirca) and erectile dysfunction (Cialis).

Other Treatments

Lung transplantation may offer hope for people with advanced pulmonary hypertension that does not respond to conservative measures.

Treatment for Gastrointestinal Problems

Agents for Acid Reflux

Treatments for abnormalities in the esophagus and stomach are generally the same as those for gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) or heartburn. Many non-prescription agents are available for the relief of heartburn. Diet and lifestyle modification plays a role, including avoiding certain "trigger" foods and raising the head of the bed.

Proton-pump or acid-pump inhibitors are probably the best drug treatments for reflux symptoms related to scleroderma. They work by inhibiting the so-called gastric acid pump that is required for the cells of the stomach to release acid. Examples include omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), pantoprazole (Protonix), esomeprazole (Nexium), and rabeprazole (Aciphex). Histamine blockers can also be used.

Side Effects

Side effects are uncommon, but can include allergic reaction, headache, stomach pain, diarrhea, and flatulence. Of some concern was a report of a very severe and widespread skin rash caused by omeprazole in a woman with scleroderma. It should be noted that this is only one incident, but people should be cautious about any skin change when taking this medication.

Agents for Impaired Stomach Muscle Contractions

Metoclopramide

Metoclopramide (Reglan) is sometimes used for people who have delayed stomach emptying.

Octreotide

Octreotide (Sandostatin) is related to a natural hormone that suppresses growth hormone, and may prove to be very helpful for people with scleroderma. Small studies have reported that this drug improved weight and nutrition. It may even help other symptoms of scleroderma.

Other agents including erythromycin, azithromycin. and domperidone may also be helpful.

Agents for Constipation

Prokinetics

Prokinetics improve the muscle action of the esophagus and enhance stomach emptying. Metoclopramide is a medication that helps to speed the movement of food through the intestine. It is typically taken by mouth in tablet or liquid form, usually four times per day. Common side effects include drowsiness, restlessness, and diarrhea. Other more rare, but serious side effects can occur. It is important to monitor symptoms and side effects while taking metoclopramide.

Prucalopride is an investigative pro-kinetic agent that significantly improved symptoms and relieved constipation in clinical trials. Similar medications are showing promise; however, these types of drugs can have serious side effects.

Treatments for Malabsorption

Antibiotics may be effective for the malabsorption syndrome associated with an increase in bacteria. Several antibiotics may be considered in a 10 to 21 day course. These may include octreotide, tetracycline, doxycycline, minocycline, amoxicillin, and cephalexin, as well as others. Probiotics may be added in between doses or courses. Probiotics may be used after antibiotic therapy.

Other recommendations for screening and management of malnutrition and malabsorption issues include:

- People with Scleroderma should weigh themselves monthly and report significant changes to caregivers.

- Suspected malnutrition cases should be referred to a dietitian and a gastroenterologist. An overall nutrition plan should be developed, including meal planning and supplements.

- Referral to a patient support group, mental health counselor, dentist, or speech pathologist should be considered, depending on specific symptoms.

- Proton pump therapy can be considered first line therapy for symptoms related to gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) or heartburn.

- A radionuclide gastric emptying study should be performed for symptoms of stomach emptying disorders.

- Parenteral or enteral nutrition may be necessary in severe cases.

Surgeries

Strictures (abnormally narrowed regions in the esophagus) may need to be opened with surgery.

Resources

- Scleroderma Foundation -- www.scleroderma.org

- Scleroderma Research Foundation -- www.srfcure.org

- The Arthritis Foundation -- www.arthritis.org

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases -- www.niams.nih.gov

- American College of Rheumatology -- rheumatology.org/

- Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium -- sclerodermaclinicaltrialsconsortium.org

- Pulmonary Hypertension Association -- phassociation.org

- American Thoracic Society -- www.thoracic.org

References

Asano Y, Fujimoto M, Ishikawa O, et al. Diagnostic criteria, severity classification and guidelines of localized scleroderma. J Dermatol. 2018;45(7):755-780. PMID: 29687475 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29687475/.

Barnett CF, De Marco T. Pulmonary hypertension due to lung disease: group 3. In: Broaddus VC, Ernst JD, King TE, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 85.

Corte TJ, Wells AU. Connective tissue diseases. In: Broaddus VC, Ernst JD, King TE, et al, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 92.

Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;390(10103):1685-1699. PMID: 28413064 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28413064/.

Distler O, Highland KB, Gahlemann M, et al. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2518-2528. PMID: 31112379 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31112379/.

Elhai M, Boubaya M, Distler O, et al. Outcomes of patients with systemic sclerosis treated with rituximab in contemporary practice: a prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(7):979-987. PMID: 30967395 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30967395/.

Ferreli C, Gasparini G, Parodi A, Cozzani E, Rongioletti F, Atzori L. Cutaneous manifestations of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53(3):306-336. PMID: 28712039 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28712039/.

Fernández-Codina A, Walker KM, Pope JE; Scleroderma Algorithm Group. Treatment algorithms for systemic sclerosis according to experts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(11):1820-1828. PMID: 29781586 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29781586/.

Goodfield MJD, Coulson IH. Scleroderma. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, Coulson IH, eds. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:chap 225.

Herrick AL, Murray A. The role of capillaroscopy and thermography in the assessment and management of Raynaud's phenomenon. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(5):465-472. PMID: 29526628 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29526628/.

Hugues, M, Herrick AL. Raynaud's phenomenon. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(1):112-132. PMID: 27421220 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27421220/.

Khanna D, Furst DE, Clements PJ, et al. Standardization of the modified Rodnan skin score for use in clinical trials of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord. 2017;2(1):11-18. PMID: 28516167 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28516167/.

Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, part 1: localized scleroderma, systemic sclerosis and overlap syndromes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(9):1401-1424. PMID: 28792092 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28792092/.

Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al; EUSTAR Coauthors. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1327-1339. PMID: 27941129 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27941129/.

Stochmal A, Czuwara J, Trojanowska M, Rudnicka L. Antinuclear antibodies in systemic sclerosis: an update. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019. PMID: 30607749 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30607749/.

Sullivan KM, Goldmuntz EA, Keyes-Elstein L, et al; SCOT Study Investigators. Myeloablative autologous stem-cell transplantation for severe scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(1):35-47. PMID: 29298160 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29298160/.

Sundaram SM, Chung L. An update on systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension: a review of the current literature. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20(2):10. PMID: 29488016 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29488016/.

Trombetta AC, Pizzorni C, Ruaro B, et al. Effects of longterm treatment with bosentan and iloprost on nailfold absolute capillary number, fingertip blood perfusion, and clinical status in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(11):2033-2041. PMID: 27744392 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27744392/.

Varga J. Etiology and pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, et al, eds. Firestein and Kelly's Textbook of Rheumatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 88.

Wigley FM, Boin F. Clinical features and treatment of scleroderma. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Gabriel SE, et al, eds. Firestein and Kelly's Textbook of Rheumatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:chap 89.

Zanatta E, Polito P, Favaro M, et al. Therapy of scleroderma renal crisis: state of the art. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17(9):882-889. PMID: 30005860 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30005860/.

|

Review Date:

7/26/2021 Reviewed By: Diane M. Horowitz, MD, Rheumatology and Internal Medicine, Northwell Health, Great Neck, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |