For most of us, a vision problem amounts to not being able to find our glasses if we need them to read or to see our favorite television show from across the room. But according to the American Foundation for the Blind, more than 20 million Americans have significant vision loss, including about 9 million baby boomers between the ages of 45 and 64. What is life like for the blind and severely visually impaired? On a hot summer day in Atlanta, I’m able to get a sample of life without sight.

I walk by brightly colored shops, bustling restaurants, and slickly designed condos, take an escalator up to Atlantic Station’s exhibition area, and then step out of the blazing sunshine and into a cool, gray and white reception area. Here I wait along with five other people to be plunged into total blackness. We are about to embark on a journey called "Dialog in the Dark."

It’s an exhibition first created over 20 years ago in Frankfurt, Germany, by Andreas Heinecke. While working for the Foundation for the Blind, Heinecke was inspired to change how "normal" people perceive those with visual impairments. He also wanted to increase respect and communication between the sighted and the blind. The result was Dialog in the Dark, which allows the sighted to "see" what it is like to be blind.

Guides who are blind or visually impaired lead groups of 10 or fewer sighted people on an hour- long adventure through environments that simulate the real world, from a traffic-filled city street to a boat ride on the ocean, from a grocery store to a lush nature park, all in total darkness. Over 20 million people in 20 countries have experienced this tour, which forces participants to zero in on senses other than sight -- their taste, smell, touch, and hearing.

Before we can participate in Dialog in the Dark, we are told to store any possessions that we could drop or lose in the dark, like pocketbooks or notebooks, in lockers. Watches and cell phones that might emit even the slightest bit of light must be locked up, too. A friendly sighted woman then briskly ushers us into a hallway where she hands us each long white canes. These are the same kind of guide sticks the blind use to navigate through their lives, including crossing streets and moving through stores. She instructs us to keep the strap looped around our wrists and to always keep the stick moving in front, touching the floor so we don’t accidentally whack each other.

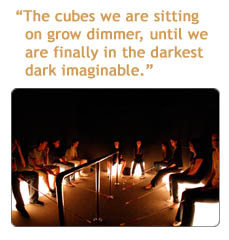

Next we enter a room with black walls and soft lighting emanating from 10 plastic cubes. We’re asked to sit on top of these glowing cubes, and our first guide leaves. She’s replaced by soft music and a recorded voice explaining what is about to happen, how our walking sticks will become our best friends, and how we will soon be relying on senses other than sight. As the voice talks, the cubes grow dimmer until we are finally in the darkest dark imaginable. There is no hint of light peeking from around a window curtain or under a door. Everywhere it is the same. We sit in total blackness.

There is a change in voices as our guide, Jason, introduces himself. He sounds friendly, articulate, and reassuring. I can’t see him, of course, but I picture a 20-something dark, slight man with a great smile. We each tell him our names, and he’s able to quickly connect our voices to our names. Within minutes of beginning our journey, in fact, Jason identifies us by name when we ask questions or need help, or if he wants to check on where exactly we are.

To get us started honing in on our other senses, we’re told to reach to the side of the cubes where we are still seated. We touch boxes there. We remove the tops to feel and smell what’s inside. I find the incredible softness of a tiny object that must be a feather, and bits of cloth all with different textures, plus something odd shaped that smells delicious when I bring it close to my face -- it’s a coffee bean.

We close the boxes, stand up, and use our canes as directed to find a railing. I put my hand on top of it, and the metal feels cold and slick. Jason explains we are going around this railing and through a door into our first environment. "Just follow my voice," he says. That’s not so easy as we move as a clump of bodies, bumping into each other in the darkness.

I’m struck by a momentary rush of anxiety and almost panic when I move through the doorway, feeling the opening with my cane.

Is there something or someone ahead of me? I have an odd instinctual urge to duck, but I reach up and find nothing overhead. Then I feel some accidental whacks to my legs from my fellow exhibition participants and I careen in the dark, accidentally bumping into one of them. We all offer nervous laughter and "I’m sorry’s," but soon we are quiet.

"Where are we?" our guide says. There is crunching underneath our feet. We are no longer on carpeting, that’s for sure. And the temperature of the air has dropped. Something brushes against my arm. I feel it and realize it’s a leaf. There’s a woodsy smell and I bend down, feeling and smelling bits of wood chips. Almost in unison, we exclaim we’re in a park setting, complete with wooden bench, a bridge with handrails which we slowly cross over, and a softly gurgling waterfall.

Again, Jason says to follow him into our next environment. It’s not as easy as it sounds in total darkness. He gives directions to "feel the wall to your right; keep following it." We end up in some place full of shelves and, we discover by feeling our way, on these shelves are cool cylindrical and rectangular objects you can shake and tell hold something inside. Other things in the environment are uneven, textured, and fragrant. "It’s a grocery store!" someone says quickly. We are exploring, with our hands, cans and boxes and recognizing onions and fruit by their smells.

Adjoining the market is a seaside environment complete with a pier. We hold onto a rope, and Jason guides us by his voice onto a "boat" that rocks gently with simulated waves. Jason asks us to think about being on the ocean. What colors did we see? What kind of birds? We answer, describing what we are seeing with the vision in our minds’ eye.

Next, we walk from this peaceful "beach" into a cacophony of blaring, discordant, and loud sounds. It’s jarring. We all know we are in a simulated environment, but it is hard not be a little afraid of what our senses register as rushing traffic just inches away. I grab my walking stick and use it more cautiously, concentrating to find the curb. Jason directs us to make sure we listen for a signal that will let us know it is safe to cross this "street." We pass and recognize, by touch, a car and a mailbox and "read" with our fingers numbers on the front of a house door.

Finally, we reach the last stop, a cafe/bar. Cool jazz is playing in the background, and we use our canes, tapping and "feeling" our way to barstools. We’re invited to order soft drinks or juice to experience taste in the dark and we witness, with our hearing, how technology can "read" dollar bills and change so the bartender knows how much money she is receiving for the drinks.

Easing our way from the barstools to cozy booths, still guided by Jason’s voice, we sit and chat for a while with our guide and each other. The nervous laughter and jostling we initially experienced has been replaced with a calm relaxation and acceptance of this dark and oddly soothing environment, and we share a friendly camaraderie (despite more than a few clobbered shins, thanks to the walking canes).

We return to the world of light and sight, hand in our canes, and I meet Jason Phillips, finally, where I can see him. Unlike my mind’s eye vision, he is tall, fair, in his thirties, and boyishly handsome, with a mop of curly brown hair.

He’s not shy about discussing his vision problems. Jason can still see a little but only when there is very high contrast between light and dark. He was born with a coloboma, a hole in his right eye that kept it from developing correctly. In the other eye, he suffers from a condition called retinal dystrophy, when the retina inside the eye breaks down. What vision he has left is growing worse over time.

Still, he is hopeful medical science will one day be able to help him see and, whether it does or not, he clearly enjoys his life and his job. After 2 weeks of training in the fall of 2008, he began working full time here, guiding the sighted into the world of the blind. How have most of the visitors to Dialog in the Dark reacted to their experience?

"Most people emerge from it thankful for their eyesight, which is understandable, but one man came out and kept saying loudly how horrible it was to be blind," Jason says. "That made me feel bad because he missed the point, I think. We all have other senses. It’s a different way of ‘seeing’ the world when you are visually impaired. We’re all people. Most people get that and say Dialog in the Dark is a positive, ‘eye opening’ experience. And that makes this job very rewarding."

Click here for more information on Dialog in the Dark.

|