According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 82 percent of Americans have one or more cell phones. They’re everywhere, including in most of our cars.

We no longer need just keys, a valid driver’s license, and money or a credit card for gas when we hit the road. The truth is, few of us feel we’re ready to drive anywhere unless we have our cell phone by our side -- and not just in case we need to make an emergency call. Take a quick look around, and it’s hard to find drivers not yakking with a phone held up to an ear or talking, hand’s free, thanks to an earpiece or wireless headset.

It’s not necessarily a safe, or productive, way to get from here to there. And in some places, it’s not even legal. In fact, momentum is gaining for a national ban on cell phone use while driving. Is that necessary? After all, can’t some of us drive just fine as we change lanes, zoom down the highway, and join a conference call?

Driving + talking = divided attentionThe problem, researchers say, is that no matter how well you multitask, no one can drive well, and safely, while talking on the phone. According to Paul A. Green, PhD, a research professor at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, the exception might be if what scientists call the "workload" of the driving situation is extremely low -- meaning that you find yourself on a perfectly straight road with no other traffic.

But in real-world situations, talking on your cell phone while driving can make you drive slower and erratically, leading, at the least, to longer trips and, at the worst, raising your risk for accidents.

Richard W. Backs, PhD, director of the Central Michigan University Center for Driving Evaluation, Education and Research, conducted divided-attention research on driving and processing verbal information at the same time. He found drivers think their driving ability isn’t compromised while they talk on their cell phones, based on measures like whether they stayed in the appropriate lane, kept a safe following distance from the car in front, or had a "close call." But, it turns out, research has revealed they weren’t paying as much attention to the road as they thought.

"We are typically unaware of the physiological changes that take place that indicate our attention resources may be compromised," explains Backs. "Unfortunately, the driving environment is typically constantly changing, and we may need to switch the focus of our attention to a potentially hazardous situation at any time.

"Our focus of attention on the cell phone conversation not only affects our ability to hear auditory information (such as sirens or squealing brakes), but it also makes us less aware of changes that take place in the visual environment, especially if they are subtle or sudden. Further, it seems that the content of the conversation may also play a role, and if it is interesting or emotional it may be very difficult for the driver to disengage from the conversation when attention is needed elsewhere."

Backs also points out that one of the main problems with cell phone conversations, as opposed to talking with someone sitting in your car, is that the person on the other end of your cell phone conversation doesn’t know what the driving environment is like and so isn’t regulating their conversation to the driving conditions like a passenger does.

A study recently published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, backs up this finding. Using a sophisticated driving simulator, University of Utah psychologist David Strayer, PhD, discovered that, when drivers talked on a cell phone, they drifted out of their lanes and missed exits more frequently than when they were chatting with a passenger in their car. Bottom line: you may think making phone calls during your commute is saving you time but you could well be wasting your time by making your trip to work take longer.

"A passenger adds a second set of eyes, and helps the driver navigate and reminds them where to go," Strayer says. "You also find when there is a passenger in the car, almost everyone takes the exit. But half the people talking on the cell phone fail to take the exit."

So what about the argument that hands-free cell phones not only keep both hands on the steering wheel but focus attention better? Previous studies by Strayer and other researchers have found that hands-free cell phones are just as distracting as the handheld variety because it’s the conversation, not holding a phone, that is the biggest distraction.

Risky behaviorA visitor from another planet encountering American teens might think they’ve evolved with a cell phone permanently attached to their ears. Adolescents rarely go anywhere without their seemingly constantly in-use cell phones -- and that adds another worry about their driving risks, which are already high.

"The adverse effects on attention are even more problematic for novice drivers (who, of course, are usually the youngest drivers) for several reasons," Backs explains. "First, recent discoveries in brain maturation indicate the parts of our brain in the frontal lobes that are responsible for decision-making and emotional control may not be fully developed until the age of 18-years-old. So, young drivers may not make driving decisions that are appropriate to the conditions. Second, these drivers do not have much experience behind the wheel and may not have encountered enough adverse situations to recognize them when they occur soon enough, or even at all."

What’s more Strayer’s research has shown that when young adults talk on cell phones while driving, their reaction times become as slow as reaction times for senior citizens. No matter how old a person is, Strayer says drivers talking on cell phones have been found to be as impaired as drivers with an 0.08 percent blood alcohol level -- the equivalent of driving drunk in most states.

Research conducted by Kenneth H. Beck, PhD, of the University of Maryland’s School of Public Health, also suggests that motorists who admit to using a cell phone while driving are also more likely to report engaging in other risky behaviors drivers (such as speeding, driving while drowsy, running a stop sign or red light, and getting behind the wheel after having a few drinks) far more than non-cell phone using drivers. "They are also more likely to report having a prior history of traffic tickets as well as crashes," Beck says.

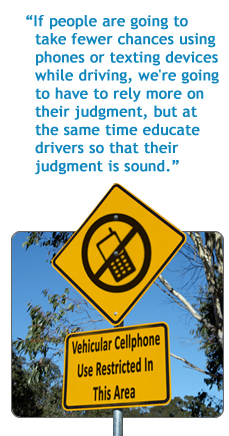

A ban on driving and cell phones?The National Safety Council has called for a nationwide ban on cell phone use while driving. That’s a prohibition opposed, not unexpectedly, by the cell phone industry. But some states have forged ahead to put legal restraints on driving while talking on cell phones.

While no state completely bans all types of cell phone use (handheld and hands-free) for all drivers, many already prohibit cell phone use by specific segments of the driving population. For example, 17 states and Washington, D.C., ban all cell phone use by new drivers as well as school bus drivers. And eight states plus D.C. have a text messaging ban for all drivers.

But is a legal solution to the potential dangers of driving and using cell phones necessary -- much less enforceable?

The University of Michigan’s Paul Green thinks we can change the widespread attitude that accepts driving and yakking on cell phones. "As with many safety campaigns, such as not driving if you’ve been drinking alcohol and requiring seat belts, it is a matter of both data and changing the safety culture. Altering what the driver can do should be part of the solution," he says.

Peter Norton, assistant professor at the University of Virginia's Engineering School and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, looks at the problem from a historian’s perspective -- and, barring some innovative enforcement technology, he doesn’t think banning driving and talking on cell phones makes sense.

"Some people are working on a cell phone that won't work in a moving car, for example, but right now that would be no barrier to anyone who wanted to talk on the phone while driving. People resent bans, subvert them, and often get them overturned. They're very hard to enforce on an unwilling public," says Norton.

"History has plainly taught us that bans of widespread practices that experts disapprove of don't work, at least not alone. Bans on littering, for example, don't stop littering. On the other hand, if the experts are right, and the practices are truly undesirable, they can get many people behind them if they just take the trouble to make their case. Rising seatbelt use has a lot more to do with drivers who've been convinced of the belts' safety benefits than with compliance with seatbelt laws," he adds.

"If people are going to take fewer chances using phones or texting devices while driving, we're going to have to rely more on their judgment, but at the same time educate drivers so that their judgment is sound."

Making it safer: cell phone and drivingJust how likely are you to have an accident while driving and talking on your cell? The University of Maryland’s Beck says more research is needed on actual crashes due to cell phone use.

"Much research to date has used survey methods or simulation studies and has shown clear impairments of driver performance when using a cell phone," he notes. "However, police reports do not typically mention whether or not cell phone use was a factor. We need to encourage the police to start recording this information on their report forms. Definitive data such as this will eventually help scientists as well as the general public understand the real risks of cell phone usage with traffic crashes."

While there’s no way that using a cell phone while driving can be absolutely safe, Backs says these strategies can help minimize your risk:

- Use your cell phone only when absolutely necessary.

- Keep conversations as short as possible.

- If the conversation is emotional or lengthy, find some place to pull over safely and continue it off the road.

- Use your cell phone only in good traffic conditions (light traffic, when you are on familiar roads, and when the weather is good).

|