Sinusitis - InDepth

Highlights

Sinusitis is an infection or inflammation of the sinuses, the air-filled chambers in the skull that are located around the nose. Symptoms of sinusitis include thick nasal discharge, facial pain or pressure, fever, and reduced sense of smell. Depending on how long these symptoms last, sinusitis is classified as acute, subacute, chronic, or recurrent.

Viruses are the most common cause of acute sinusitis, but bacteria are responsible for most of the serious and chronic cases.

Home remedies such as nasal saline (salt) washes are helpful for removing mucus and relieving congestion. People with sinusitis should drink plenty of fluids to avoid dehydration. Water, which helps lubricate the mucous membranes, is the best fluid to drink.

Medication depends on the type of sinusitis and its cause. Nonprescription pain relievers such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen can help mild-to-moderate pain. Decongestants may help relieve congestion, but they do not cure sinusitis. Antihistamines are not generally recommended because they can dry the mucus and worsen the condition; however, they may be used when sinusitis is associated with allergies. Cough or cold medication is not recommended for children younger than age 4.

Because many cases of acute sinusitis resolve within 2 weeks with nonprescription treatments and home remedies, health care providers generally wait at least 7 days before prescribing an antibiotic.

For chronic sinusitis, topical nasal corticosteroids, oral steroids, and antibiotics are the main treatments. Other drugs may also be prescribed. If drugs are ineffective, some people with chronic sinusitis may need surgery.

Introduction

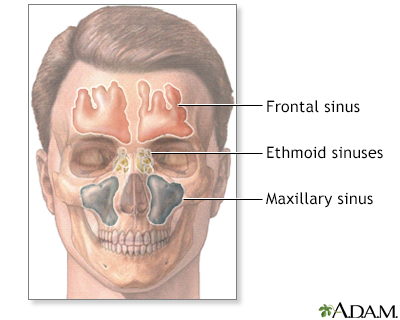

Sinusitis (also called rhinosinusitis) is inflammation of the mucous lining of the nasal passages and sinus cavities. The sinuses are air-filled chambers in the skull (behind the forehead, nasal bones, cheeks, and eyes) that are lined with mucous membranes.

Four pairs of sinuses, known as the paranasal air sinuses, connect to the nasal passages (the two airways running through the nose):

- Frontal sinuses (behind the forehead)

- Maxillary sinuses (behind the cheekbones)

- Ethmoid sinuses (behind the nose)

- Sphenoid sinuses (behind the eyes)

Sinusitis occurs if obstruction or congestion causes the paranasal sinus openings to become blocked. When the sinus openings become blocked or too much mucus builds up in the chambers, bacteria and other germs can grow more easily, leading to infection and inflammation.

Sinusitis is classified based on how long symptoms last as:

- Acute. Less than 4 weeks. Symptoms resolve completely.

- Subacute. Between 4 and 12 weeks. Symptoms resolve completely.

- Chronic. 12 weeks or longer inflammation of paranasal sinuses and nasal cavities with persistent upper respiratory tract symptoms.

- Recurrent acute. Acute infections that last less than 30 days each and recur after 10 or more days of resolution of the symptoms.

- Acute bacterial sinusitis superimposed on chronic sinusitis. New symptoms appear in addition to chronic symptoms. Treatment resolves the new symptoms but not the chronic ones.

Sinusitis is always accompanied (and usually preceded) by rhinitis, which is inflammation of the mucous membrane of the nasal cavities. The two conditions share common symptoms such as nasal obstruction and discharge.

Causes

Acute sinusitis can be caused by viral, bacterial, or fungal infections. Allergens and environmental irritants are other possible causes. In most cases, acute sinusitis is caused by an upper respiratory tract viral infection, such as the common cold, and usually resolves on its own.

Chronic sinusitis refers to long-term swelling and inflammation of the sinuses. Chronic sinusitis can result from recurring episodes of acute sinusitis, or it can be caused by other health conditions, like:

- Asthma and allergic rhinitis

- Immune disorders

- Structural abnormalities in the nose, like a deviated septum or nasal polyps

Viruses

In almost 90% cases in adults and 50% to 70% cases in children, acute sinusitis have a viral cause. Acute sinusitis typically starts with the common cold virus. A cold can set the stage for sinusitis by causing inflammation and congestion in the nasal passages, leading to obstruction in the sinuses.

Bacteria

A small percentage of acute sinusitis, and possibly chronic sinusitis cases, are caused by bacteria. Bacteria are normally present in the nasal passages and throat and are usually harmless. However, when a cold or other viral upper respiratory infection blocks the nasal passage and prevents the sinuses from draining, bacteria can multiply within the mucous lining of the sinuses, causing sinusitis.

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis (a common cause of childhood illnesses) are the bacteria most often linked to acute sinusitis. These bacteria plus other strains, such as Staphylococcus aureus, are also associated with chronic sinusitis. (The role of bacteria in chronic sinusitis is still being debated.) Bacterial sinusitis usually causes more severe symptoms and lasts longer than viral sinusitis.

Fungi

An allergic reaction to fungi is a cause of some chronic rhinosinusitis cases. Various fungi such as species of Aspergillus, Candida, Mucor, Rhizopus, and others can cause fungal sinus disease. However, Aspergillus is the most common fungus associated with sinusitis. Fungal infections tend to occur in people with sinusitis who also have diabetes, leukemia, AIDS, or other conditions that impair the immune system. Fungal infections can also occur in people with healthy immune systems, but they are far less common.

Allergies, asthma, and sinusitis often overlap. Seasonal allergic rhinitis and other allergies that cause mucus blockage may predispose people to develop sinusitis. Many of the immune factors observed in people with chronic sinusitis resemble those that appear in allergic rhinitis, suggesting that in some people sinusitis is due to an allergic response.

Asthma is also strongly associated with sinusitis and many people have both conditions. Some studies suggest that sinusitis may worsen asthma symptoms.

Chronic sinusitis and recurrent acute sinusitis are also associated with disorders that weaken the immune system or produce airway inflammation or persistent thickened stagnant mucus. These conditions include diabetes, AIDS, cystic fibrosis, Kartagener syndrome, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

Structural abnormalities in the nose can cause a blockage, thereby increasing the risk for chronic sinusitis. These abnormalities include:

- Polyps (small benign growths) in the nasal passage that block mucus drainage and may restrict airflow. Polyps can result from previous sinus infections that caused overgrowth of the nasal membrane.

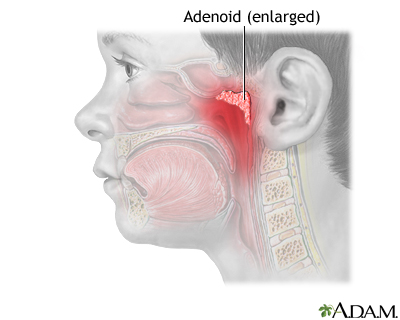

- Enlarged adenoids can lead to sinusitis.

Adenoids are masses of tissue located high on the posterior wall of the pharynx. They are made up of lymphatic tissue, which trap and destroy germs in the air that enter the nasopharynx.

- Cleft palate.

- Tumors.

- Deviated septum (a common structural abnormality in which the septum, the midline cartilage separating the two sides of the nose, is shifted to one side.)

- Other obstructive anatomic variants such as extra air cells adjacent to sinus openings.

Risk Factors

Sinusitis is a very common disease.

Before the immune system matures, all infants are susceptible to respiratory infections. Young children (age less than 2 years)are prone to colds and may have 6 to 8 bouts every year; however, 10% to 15% children may have at least 12 bouts every year. Smaller nasal passages make children more vulnerable to upper respiratory tract infections than older children and adults. True chronic sinusitis in children, however, is rare since the nasal sinuses do not develop fully until later in childhood. Ear infections such as otitis media are also associated with sinusitis.

Older people are at higher risk for sinusitis. Their nasal passages tend to dry out with age. In addition, the cartilage supporting the nasal passages weakens, causing airflow changes. They also have diminished cough and gag reflexes and weakened immune systems and are at greater risk for serious respiratory infections than are young and middle-aged adults.

People with asthma or allergies are at increased risk for inflammation in the sinuses. People with a combination of polyps in the nose, asthma, and sensitivity to aspirin (called Samter's triad, ASA triad, or aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease) are at very high risk for chronic or recurrent acute sinusitis.

Some hospitalized people are at higher risk for sinusitis, particularly those with:

- Head injuries

- Conditions requiring insertion of tubes through the nose

- Breathing aided by mechanical ventilators

- Weakened immune system

A number of medical conditions put people at risk for chronic sinusitis. They include:

- Diabetes (types 1 and 2.)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

- AIDS and other disorders of the immune system.

- Oral or intravenous steroid treatment.

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland.)

- Cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder in which the mucus is very thick and builds up.

- Kartagener syndrome, a genetic disorder that impairs function of cilia, the hair-like structures that normally move mucus through the respiratory tract.

- Autoimmune conditions such as Sjogren's syndrome.

Dental Problems

Bacteria associated with infections from dental problems or procedures can trigger cases of maxillary sinusitis.

Changes in Atmospheric Pressure

People who experience changes in atmospheric pressure, such as while flying, may face an increased risk of developing sinusitis.

Cigarette Smoke and Other Air Pollutants

Air pollution from industrial chemicals, cigarette smoke, or other pollutants can damage the cilia responsible for moving mucus through the sinuses. It is still not clear whether air pollution is an important cause of sinusitis and which specific pollutants are critical factors. Cigarette smoke, for example, poses a small but definite risk for sinusitis in adults. Secondhand smoke does not appear to have any significant effect on adult sinuses, although it may pose a risk for sinusitis in children.

Complications

Bacterial sinusitis is nearly always harmless (although uncomfortable and sometimes even very painful). If an episode becomes severe, antibiotics generally eliminate further problems. In rare cases, however, bacterial sinusitis can cause very serious infections.

Infection of the Frontal Bone

Osteomyelitis is infection of the bones. In rare cases, sinusitis can lead to infection of the forehead and other facial bones. In such cases, the person usually experiences headache, fever, and a soft swelling over the bone known as Pott puffy tumor.

Infection of the Eye Socket

Infection of the eye socket (orbital cellulitis), which causes swelling and subsequent drooping of the eyelid, is a rare but serious complication of ethmoid sinusitis. In these cases, the person loses movement in the eye, and pressure on the optic nerve can lead to vision loss, which is sometimes permanent. Fever and severe illness are usually present.

Brain Infection

The most dangerous complication of sinusitis, particularly frontal and sphenoid sinusitis, is the spread of infection by anaerobic bacteria to the brain, either through the bones or blood vessels. Abscesses, meningitis, and other life-threatening conditions may result. In such cases, the person may experience mild personality changes, headache, altered consciousness, visual problems, and, finally, seizures, coma, and death.

Blood clots (called cavernous sinus thrombosis) are another rare but potentially serious complication from sphenoid sinusitis. If a blood clot forms in the sinus area around the front and top of the face, symptoms are similar to infection of the eye socket. In addition, the pupil may be fixed and dilated. Although symptoms usually begin on one side of the head, the process usually spreads to both sides.

Many people with moderate-to-severe asthma also have sinusitis and allergic rhinitis. The relationship between sinusitis and asthma is not clear, but sinusitis appears to predispose people to more severe asthma attacks. Evidence suggests that treating one condition can have a beneficial impact on the other.

Pain, fatigue, and other symptoms of chronic sinusitis can have significant effects on quality of life. This condition can result in emotional distress, impaired normal activity, and reduced attendance at work or school. According to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, the average person with sinusitis misses about 4 work days a year, and sinusitis is one of the top 10 medical conditions that most adversely affect employers.

Symptoms

Sinus symptoms are very common during a cold or the flu. In most cases, they are due to the effects of the infecting virus and resolve when the infection does. General symptoms of acute sinusitis (both viral and bacterial) include:

- Nasal congestion or discharge

- Headache

- Facial pain, pressure, or feeling of fullness

- Cough or scratchy throat

- Fever

- Diminished or absent sense of smell

- Other symptoms, such as ear pain or pressure, dental pain, bad breath, and fatigue

It is important to differentiate between inflamed sinuses associated with cold or flu virus and sinusitis caused by bacteria, but it can be difficult to do so. In general, with viral sinusitis, symptoms usually last 7 to 10 days and then improve. Acute bacterial sinusitis, in contrast to viral sinusitis, usually takes one of the following three paths:

- Persistent. Symptoms that last more than 10 days and do not improve. Nasal discharge (either clear or colored) and daytime cough are common.

- Severe. Symptoms, with a high fever (at least 102oF [38.8oC]) and thick, green nasal discharge or facial pain that lasts for at least 3 to 4 days starting from the beginning of the illness. (With viral sinusitis, fever usually disappears within the first day or two and green discharge does not appear until after the fourth day.)

- Worsening. Symptoms following a typical viral upper respiratory infection. Symptoms appear to improve but are then followed suddenly by another set of worsening symptoms (return of fever, cough, severe headache, or increase in nasal discharge) after 5 to 6 days ("double-sickening".)

If symptoms suggest acute bacterial sinusitis, antibiotic treatment is warranted. Bacterial sinusitis is not as common as viral sinusitis, but bacteria are responsible for most serious cases of sinusitis.

Children

In children, the most common signs and symptoms of acute bacterial sinusitis are daytime cough (which may worsen at night), nasal discharge, and fever. Bad breath, fatigue, headache, and decreased appetite are also common symptoms in young children, but they do not necessarily indicate sinusitis.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that health care providers diagnose acute bacterial sinusitis when a child with an upper respiratory infection has:

- Symptoms that last more than 10 days

- Severe onset of symptoms (including fever and nasal discharge) lasting at least 3 days in a row

- Symptoms (like nasal discharge, fever, or cough) that get worse after initially improving

Children with worsening or severe symptoms should be treated with antibiotics. For other children, watchful waiting is appropriate to see if the infection clears up on its own.

With chronic sinusitis:

- Any of the sinusitis symptoms listed previously may be present

- Symptoms are more vague and generalized than with acute sinusitis

- Fever may be absent or low-grade

- Symptoms of sinusitis last 12 weeks or longer

- Symptoms occur throughout the year, even during nonallergy seasons

Rare complications of sinusitis can produce additional symptoms, which may be severe or even life-threatening. Symptoms indicating a medical emergency include:

- Increasing severity of symptoms

- Eyes that are red, bulging, or painful (if the sinus infection occurs around the eyes)

- Swelling and drooping eyelid

- Loss of eye movement (possible infection in the eye socket)

- Vision changes

- Fixed or dilated pupil

- Symptoms spreading to both sides of face (may indicate blood clot)

- Development of severe headache, altered vision

- Mild personality or mental changes (may indicate spread of infection to brain)

- Soft swelling over the bone (may indicate bone infection)

Allergies

Symptoms of both sinusitis and allergic rhinitis include nasal obstruction and congestion. The conditions often occur together. People with allergies and no sinus infection may have:

- Thin, clear, and runny nasal discharge

- Itchy nose, eyes, or throat (these symptoms do not occur with bacterial sinusitis)

- Recurrent sneezing

- Symptoms of allergies that appear only during exposure to allergens

Migraine and Other Headaches

Many primary headaches, particularly migraine or cluster headaches, may closely resemble sinus headache. Migraine and sinus headaches may even coexist in many cases. Sinus headaches are usually more generalized than migraines. But it is often difficult to tell them apart, particularly if headache is the only symptom of sinusitis.

Trigeminal Neuralgia

In some cases, headache that persists after successful treatment of chronic sinusitis may be due to neuralgia (nerve-related pain) in the face.

Other Conditions

A number of other conditions can mimic sinusitis, including:

- Dental problems.

- A foreign object in the nasal passage.

- Temporal arteritis (headache caused by inflamed arteries in the head).

- Persistent upper respiratory tract infections.

- Temporomandibular disorders (problems in the joints and muscles of the jaw hinges).

- Vasomotor rhinitis, a condition in which the nasal passages become congested in response to irritants or stress. It often occurs in pregnant women.

Diagnosis

See your health care provider if you have sinusitis symptoms that do not clear up within a few days, are severe, or are accompanied by high fever or sudden generalized illness.

The first goal in diagnosing sinusitis is to rule out other possible causes of symptoms, and then determine:

- The site where the infection has occurred

- Whether the condition is acute or chronic

- Whether the condition is caused by virus or bacteria

Medical History

You should describe to your provider all of your symptoms, such as nasal discharge and specific pain in the face and head, including eye and tooth pain.

The provider will evaluate your symptoms and take a thorough medical history, including:

- Any history of allergies, asthma, or headaches.

- Recent upper respiratory infections (colds, flu, and infection) and how long they lasted.

- History of sinusitis episodes that did not respond to antibiotic treatment.

- Exposure to cigarette smoke or other environmental pollutants.

- Recent air travel.

- Recent dental procedures.

- Medications (particularly decongestants.)

- Any known structural abnormalities in the nose and face.

- Injury to the head or face.

- History of medical conditions that can produce tender areas in the face or sinus regions, and nonspecific symptoms of ill health.

- Any family or personal history of immune disorders, cystic fibrosis, or Kartagener syndrome.

The provider will ask how long your symptoms have lasted:

- If you have been sick less than 10 days and your symptoms are not getting worse, you likely have acute viral sinusitis.

- If you have been sick at least 10 days and have not improved or your symptoms worsened after beginning to feel better ("double sickening"), you likely have acute bacterial sinusitis. Symptoms such as high fever and thick, colored nasal discharge may indicate a bacterial infection.

- It is important to diagnose if you have sinusitis caused by virus or bacteria because the treatment approaches are different.

The provider will press the forehead and cheekbones to check for tenderness and other signs of sinusitis, including yellow to yellow-green nasal discharge. The doctor will also check the inside of the nasal passages using a device with a bright light to look for nasal obstruction and any structural abnormalities.

Nasal endoscopy (NE) involves the insertion of a flexible or rigid tube with a fiberoptic light on the end into the nasal passage. NE allows detection of even very small abnormalities in the nasal passages. It can evaluate structural problems of the nasal septum, as well as the presence of soft tissue growths such as polyps. NE may also identify small amounts of pus draining from the opening of a sinus. Bacterial cultures can be taken from samples removed using endoscopy. NE is also used for treating sinusitis.

Imaging tests are not usually needed to diagnose acute sinusitis.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT scanning is the best method for viewing the paranasal sinuses. However, CT scans are not recommended for most cases of uncomplicated acute bacterial sinusitis. They are only recommended for acute sinusitis if there is a severe infection, complications, or a high risk for complications, especially those that may affect the eyes or central nervous system.

CT scans can be useful for diagnosing chronic or recurrent acute sinusitis and for planning operations. They show inflammation and swelling and the extent of the infection, including in deeply hidden air chambers that x-rays and nasal endoscopy may miss. They may also detect fungal infections.

X-Rays

X-rays used to be commonly used, but they are not as accurate as endoscopy and CT scans for identifying abnormalities in the sinuses, particularly the ethmoid sinuses. X-rays are not indicated to make a diagnosis of acute sinusitis.

Sinus puncture with bacterial culture, while very sensitive for diagnosing a bacterial sinus infection, is not commonly done. It is invasive and can be painful, and is performed only when people are at risk of having unusual infections or serious complications, or if antibiotics have not worked.

Sinus puncture involves using a needle to withdraw a small amount of fluid from the sinuses. It requires a local anesthetic and is performed by a specialist. More routinely, the gold standard has become endoscopic-guided cultures which can be done at the time of office endoscopy and is much less invasive with similar accuracy. In either case, the fluid is then cultured to determine what type of bacteria is causing sinusitis.

Prevention

The best way to prevent sinusitis is to avoid colds and influenza. If you are unable to avoid these viruses, the next best way to prevent sinusitis is to effectively treat colds and influenza.

Cold and flu viruses spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes. These viruses can also be transmitted by shaking hands. Everyone should always wash their hands before eating and after going outside. Ordinary soap is sufficient. Waterless hand cleansers that contain an alcohol-based gel are also effective. Antibacterial soaps add little protection, particularly against viruses. Wiping surfaces with a solution that contains 1 part bleach to 10 parts water is very effective in killing viruses.

Influenza Vaccine

Most people should receive an annual influenza vaccination according to the flu season of their country. Tropical regions have year around activity of the influenza virus. In temperate regions, influenza virus is most active during winters, that is November to April in Northern hemisphere and May to September in Southern Hemisphere. Influenza viruses change from year to year; therefore, influenza vaccines are redesigned annually to match the anticipated viral strains.

Flu vaccines are now recommended for virtually everyone over 6 months of age, except for those allergic to eggs or other vaccine compounds.

Pneumococcal Vaccines

Pneumococcal vaccines protect against S. pneumoniae (also called pneumococcal) bacteria, the most common bacterial cause of respiratory infections. Pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for all infants younger than 15 months and for all adults age 65 and older. The vaccine is also recommended for children and for adults younger than age 65 who have health conditions that compromise their immune system or raise their risk for infection, as well as for smokers and people with asthma.

Septoplasty

Deviated septum makes you prone to develop sinusitis. Septoplasty, a surgical procedure to correct this deviation, is performed to relieve the nasal obstruction. The goal of the surgery is to achieve maximum improvement of the symptoms. Septoplasty techniques have changed drastically with time. The procedure is individualized and your surgeon choses the best suited technique according to symptoms.

Avoid Smoking

Smoking (active and passive) is an established risk factor for the development of sinusitis. Smoking affects the normal nasal mucosa and lowers innate immunity. Quitting smoking and avoiding second hand smoke reduces your risk to develop sinusitis.

Air Moisture

Air is drier in winters due to low temperatures. Low air moisture has direct effects on the internal environment of the nose. A dry sinus is at greater risk to develop an infection. Using a clean humidifier to maintain the moisture in ambient air helps prevent the sinus drying and in turn sinusitis.

Treatment

General treatment goals for sinusitis aim to:

- Reduce swelling

- Stop infection

- Drain the sinuses

- Ensure that the sinuses remain open

Most people with sinusitis do not require aggressive treatment. Home remedies such as nasal salt water (saline) washes and drinking plenty of fluids can be very helpful. Medications may be given if necessary. Ask your health care provider before taking an antihistamine (like Benadryl, Claritin, or Zyrtec) which may or may not be helpful for sinusitis. Specific treatment approaches depend on whether sinusitis is acute or chronic, and whether it is caused by a virus or bacteria.

Treatment of Acute Viral Sinusitis

Most cases of sinusitis are caused by viruses, which do not respond to antibiotics. Acute viral sinusitis generally clears up on its own within 7 to 10 days. Symptoms of acute viral sinusitis can be treated with nasal saline washes, pain relievers like ibuprofen (Advil, generic) and acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic), and nasal spray corticosteroids.

Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis

Only 10% cases of sinusitis in adults and 30% to 50% cases of sinusitis in children are acute bacterial sinusitis. Antibiotics can treat bacterial infection, but not all cases of acute bacterial sinusitis require antibiotic treatment. Guidelines for treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis recommend:

- Watchful waiting for up to 7 days to see if the sinusitis clears up on its own. Your provider may give you a prescription for an antibiotic to take if you do not get better after 7 days or if your sinusitis worsens during this time.

- If an antibiotic is needed, amoxicillin with or without clavulanate is recommended. You will take the antibiotic for 5 to 10 days.

- For children who have symptoms for more than 10 days, doctors may wait and watch for an additional 3 days before prescribing antibiotics to see if the infection clears up on its own. Children who have severe or worsening symptoms should receive immediate treatment with antibiotics.

- For symptom relief, use saline nasal rinses, pain relievers, and decongestants. Do not use nasal decongestants for more than 3 days in a row. Nasal steroid sprays are another option, but have limited benefit.

Treatment of Chronic Sinusitis

Chronic sinusitis typically results from damage to the mucous membrane from a past, untreated acute sinus infection but it can also be caused by structural problems or other medical conditions. Treatments include:

- Corticosteroid nasal sprays and saline nasal irrigation are standard treatments.

- A thorough diagnostic workup should be performed to rule out any underlying conditions, including allergies, asthma, immune system problems, gastroesophageal reflux disorder, and structural problems in the nasal passages. If a primary trigger for chronic sinusitis can be identified, it should be treated or controlled.

- If there is no improvement, surgery may be considered. For some people with chronic sinusitis the condition is not curable, and the goal of treatment is to improve the quality of life.

- The role of antibiotic treatment for chronic sinusitis is controversial. Special types of antibiotics may be used, and treatment may be needed for a longer time.

- In some severe cases or in cases where there is severe nasal congestion and inflammation, a short course of oral steroids are given to decrease swelling and improve sinus drainage. This treatment is generally very effective.

- Antifungal medications are not recommended.

Emergency care is required if infection spreads beyond the nasal sinuses into the bone, brain, or other parts of the skull. High-dose antibiotics are administered intravenously, and emergency surgery is almost always necessary in such cases.

Lifestyle Changes

Home remedies that open and hydrate the sinuses are often the only treatment necessary for mild sinusitis that is not accompanied by signs of acute infection.

Drinking plenty of fluids and getting lots of rest is still the best advice for easing mild symptoms:

- Water is the best fluid because it helps lubricate the mucous membranes.

- Hot steaming liquid such as chicken soup or herbal teas helps with congestion.

- Spicy foods that contain hot peppers or horseradish may help clear sinuses.

- Inhaling steam 2 to 4 times a day is extremely helpful, costs nothing, and requires no expensive equipment. Sit comfortably and lean over a bowl of hot water (no one should ever inhale steam from water as it boils) while covering the head and the bowl with a towel so the steam remains under the cloth. The steam should be inhaled continuously for 10 minutes. A mentholated or other aromatic preparation may be added to the water. Long, steamy showers, vaporizers, and facial saunas are alternatives.

A nasal wash can be helpful for removing mucus from the nose and relieving sinusitis symptoms. A saline (salt water) solution can be purchased in a spray bottle at a drug store or made at home. (Mix 1 teaspoon of table, Kosher, or sea salt with 2 cups of warm water. Some people add a pinch of baking soda.) If you prepare your own saline solution, use bottled or boiled water, not plain tap water, to avoid potential infections with a dangerous type of water-dwelling parasite called Naegleria fowleri. Perform the nasal wash several times a day.

A simple method for administering a nasal wash is:

- Lean over the sink head down.

- Pour some solution into the palm of the hand and inhale it through the nose, one nostril at a time.

- Spit out the remaining solution.

- Gently blow the nose.

Neti pots have also become popular in recent years for prevention and treatment of sinusitis. To do nasal irrigation with a saline solution through a Neti pot:

- Lean over the sink with your head tilted to one side.

- Insert the spout of the Neti pot into the upper nostril.

- Slowly pour the salt water into your nose while continuing to breathe through your mouth.

- The water will flow through the upper nostril and out through the lower nostril.

- When the water finishes dripping out, blow your nose.

- Reverse the tilt of your head and repeat the process with the other nostril.

You can also use either a bulb syringe or a sinus rinse squeeze bottle sold at most pharmacies which provides more vigorous irrigations to break up thick, sticky mucous that often accompanies chronic infection.

Medications

Antibiotic drugs are used to treat bacterial, not viral, infections. Unfortunately, because of the overuse and improper use of antibiotics, many types of bacteria no longer respond to antibiotic treatment. The bacteria have become resistant to these drugs.

Amoxicillin, a type of penicillin, is the main antibiotic used for mild-to-moderate acute bacterial sinusitis, but due to bacterial resistance it has become less effective. Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin, generic) may be used as an alternative to amoxicillin. It is a type of penicillin that works against a wide spectrum of bacteria.

People who have a history of penicillin allergy cannot take amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate. They will need to take another type of antibiotic such as doxycycline or clindamycin. Some people with penicillin allergy can take cephalosporin antibiotics. Levofloxacin and related antibiotics should only be used when other options are not available due to possible serious side effects.

Side effects of antibiotics may include:

- Upset stomach.

- Vaginal infections (taking supplements of acidophilus or eating yogurt with active cultures may help restore healthy bacteria that offset the risk for such infections.)

- Interactions with certain drugs, including some over-the-counter medications. Inform your doctor of all medications you are taking and of any drug allergies.

- Allergic reactions can range from mild skin rashes to rare but severe, and even life-threatening anaphylactic shock.

Nasal-spray corticosteroids, commonly called nasal steroid sprays, help reduce inflammation and mucus production. They may take up to several weeks of use to have an effect.

Corticosteroids that are available in nasal spray form and are approved for treating nasal allergy symptoms include:

- Triamcinolone acetonide (Nasacort Allergy 24HR)

- Mometasone furoate monohydrate (Nasonex)

- Fluticasone propionate (Flonase Allergy Relief)

- Beclomethasone dipropionate (Beconase, Vancenase), flunisolide (Nasalide), and budesonide (Rhinocort)

- These nasal sprays are also approved for children (ages vary depending on brand)

Side Effects

Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs. Although oral steroids can have many side effects, the nasal-spray form affects only local areas, and the risk for widespread side effects is very low unless the drug is used excessively.

Side effects of nasal corticosteroids may include:

- Dryness, burning, stinging in the nasal passage

- Headache

- Nosebleed (inform your health care provider)

When taking a nasal steroid spray, it is very important that you direct the tip of the bottle towards the cheek or eye on that side of the face. This will direct the medicine towards the swollen glands and sinus passages and away from the central septum or cartilage which can be the source of nosebleeds. Also, do not sniff in deeply while using the spray because this directs all the medicine into the back of your nose and into your mouth instead of keeping it inside the nose where it should be.

Decongestants are drugs that help reduce nasal congestion. They are available in both pill and nasal spray forms. However, decongestants will not cure sinusitis. They may actually worsen sinusitis by increasing sinus inflammation if used too long. Nasal spray decongestants should not be used for more than 3 days in a row.

Due to the lack of evidence for the benefit of nasal decongestants in treating sinusitis, the FDA ordered manufacturers of over-the-counter (OTC) nasal decongestant products to remove all references to sinusitis from their labeling. The Infectious Diseases Society of America does not recommend nasal or oral decongestants for patients with acute bacterial sinusitis.

Your health care provider may still recommend that you take either an OTC or prescription nasal decongestant to help relieve blockage symptoms associated with sinusitis. If you think you have sinusitis, check with your provider before taking a decongestant.

Decongestants should never be used in infants and children under age 4, and some doctors recommend not giving them to children under age 14. Children are at particular risk for central nervous system side effects, including convulsions, rapid heart rate, loss of consciousness, and death.

Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl, generic) are included in many cold and allergy medications. Because they dry and thicken nasal secretions, they make sinus drainage difficult and may worsen sinusitis. In general, people with sinusitis should not take antihistamines.

Surgery

Surgery can unblock the sinuses when drug therapy is not effective or if there are other complications, such as structural abnormalities or fungal sinusitis.

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is the standard procedure for most people who require surgical management of chronic sinusitis or polyposis. The procedure allows correction of obstructions, including polyps, ventilation, and drainage to aid healing.

Candidates for the Procedure

In general, surgery is reserved for people who have tried and failed medical therapy, including several courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics, nasal corticosteroids, and sinus drainage (when appropriate).

People who may benefit from sinus surgery include those with:

- Nasal or sinus polyps who have not responded to intranasal or oral corticosteroids

- Congenital anatomic abnormalities

- Evidence of bone involvement

- HIV/AIDS or other immune system impairments who have chronic or recurrent sinusitis

Procedure

The surgery generally proceeds as follows:

- Adults and children need a general anesthetic.

- Before the procedure, a computed tomography (CT) scan is taken to help the surgeon plan the procedure and to guide the surgery.

- A rigid sinus endoscope that has a light and camera head attached are inserted through the nostrils to visualize the anatomy of the nose and sinuses.

- The surgeon uses special instruments to remove diseased bone or tissue and clear obstructions. Shavers are used to gently remove soft tissue such as polyps. Miniature bone cutters are sometimes used to open the floor of the frontal sinus and restore drainage.

- In some milder cases where the anatomy is not severely obstructed, a procedure called "Balloon sinuplasty" is performed in which a catheter with an inflatable balloon is used to enlarge the natural opening of one or more sinuses. Your surgeon will determine which one is the best surgery for you depending on your history and anatomy.

Complications

Serious complications of FESS are very rare, but may include cerebrospinal fluid leakage, meningitis, hemorrhage, injury to the eye or eye socket, or infection.

Postsurgical Care

Postsurgical care involves the following:

- You will experience a dull ache around the nose and sinus cavity that can be treated with pain medication.

- Following surgery, you should flush the sinuses twice daily with a saline or alkaline solution.

- Antibiotics may be prescribed for several weeks until postnasal drip has stopped. Corticosteroid sprays and antihistamines may be needed.

Success Rates

It may take several months for the mucous membranes to completely recover, but most people have good-to-excellent relief of their symptoms after surgery. Children may need a second procedure 2 to 3 weeks after the first surgery to remove crusty matter.

A newer type of surgical procedure threads a small balloon through the sinus passages. As the balloon is gently opened, the sinus passages expand, allowing drainage to occur.

This procedure is best suited for select people with sinusitis disease in the maxillary (behind the cheekbones), frontal (behind the sides of the forehead), and sphenoid (behind the eyes) sinus regions. It is inappropriate for people with disease in the ethmoid (between the eyes) sinuses because of the risk of eye injury.

Endoscopy is now used in most cases of chronic sinusitis, but in severe cases, invasive surgery using conventional scalpel techniques may be required to remove infected areas. This may be the case with acute ethmoid sinusitis in which pus breaks through the sinus and threatens the eye, very severe frontal sinusitis, invasive fungal sinusitis, or when cancer is present in the sinuses.

Resources

- American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery -- www.entnet.org/

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology -- www.aaaai.org

- American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology -- acaai.org

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease -- www.niaid.nih.gov

- Infectious Diseases Society of America -- www.idsociety.org

- American Academy of Pediatrics -- www.aap.org

- American Rhinologic Society -- www.american-rhinologic.org

References

Benninger MS, Stokken JK. Acute rhinosinusitis: pathogenesis, treatment, and complications. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund V, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:chap 46.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Sinus infection (sinusitis). www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/community/for-patients/common-illnesses/sinus-infection.html. Updated August 27, 2019. Accessed November 5, 2019.

Chong LY, Head K, Hopkins C, Philpott C, Burton MJ, Schilder AG. Different types of intranasal steroids for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD011993. PMID: 27115215 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27115215.

Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(8):e72-e112. PMID: 22438350 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22438350.

DeMuri GP. Wald ER. Sinusitis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 62.

Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A; High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians and for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Appropriate antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infection in adults: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(6):425-434. PMID: 26785402 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26785402.

Head K, Chong LY, Piromchai P, et al. Systemic and topical antibiotics for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD011994. PMID: 27113482 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27113482.

Hersh AL, Jackson MA, Hicks LA; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Principles of judicious antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1146-1154. PMID: 24249823 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24249823.

Kozak FK, Ospina JC, Cardenas MF. Characteristics of Normal and Abnormal Postnatal Craniofacial Growth and Development. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund V, et al, eds. Cummings Otolaryngology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:chap 185.

Lemiengre MB, van Driel ML, Merenstein D, et al. Antibiotics for acute rhinosinusitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:CD006089. PMID: 30198548 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30198548.

Lopez SMC, Williams JV. The common cold. In: Kliegman RM, St Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 407.

Luk LJ, DelGaudio JM. Topical Drug Therapies for Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2017;50(3):533-543. PMID: 28389018 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28389018.

Pappas DE, Hendley JO. Sinusitis. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 408.

Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(4):598-609. PMID: 25833927 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25833927.

Rosenfeld RM. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Acute sinusitis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):962-970. PMID: 27602668 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27602668.

Sedaghat AR. Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(8):500-506. PMID: 29094889 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29094889.

Treanor JJ. Influenza viruses (including avian influenza and swine influenza). In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 165.

US Food & Drug Administration website. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur together. www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-advises-restricting-fluoroquinolone-antibiotic-use-certain. Updated September 25, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2019.

US Food & Drug Administration website. Use caution when giving cough and cold products to kids. www.fda.gov/drugs/special-features/use-caution-when-giving-cough-and-cold-products-kids. Updated February 08, 2018. Accessed November 4, 2019.

Wald ER, Applegate KE, Bordley C, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e262-e280. PMID: 23796742 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23796742.

Wyler B, Mallon WK. Sinusitis update. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2019;37(1):41-54. PMID: 30454779 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30454779.

Reviewed By: Josef Shargorodsky, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.