Alcohol use disorders - InDepth

Highlights

You may have an alcohol use disorder if in the past year you have:

- Had times when you ended up drinking more, or longer, than you intended.

- More than once wanted to cut down or stop drinking, but couldn't.

- Spent a lot of time drinking, being sick or getting over other aftereffects of drinking.

- Wanted a drink so badly that you couldn't think of anything else.

- Found that drinking, or being sick from drinking, often interfered with taking care of your home or family, or caused job or school troubles.

- Continued to drink even though it was causing trouble with your family or friends.

- Given up or cut back on activities that were important, interesting, or pleasant to you, in order to drink.

- More than once gotten into situations while drinking or after drinking that increased your chances of getting hurt (such as driving, swimming, using machinery, walking in a dangerous area, or having unsafe sex).

- Continued to drink even after having had a memory blackout or even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious or adding to another health problem.

- Had to drink much more than you once did to get the effect you want or found that your usual number of drinks had much less effect as before.

- Found that when the effects of alcohol were wearing off, you had withdrawal symptoms such as shakiness, restlessness, trouble sleeping, nausea, sweating, a racing heart, a seizure, or sensed things that were not there.

There are many screening tests that doctors use to check for alcohol use disorders. Some of these tests you can take on your own. The CAGE test is an acronym for the following questions. It asks:

- Have you ever felt you should CUT (C) down on your drinking?

- Have people ANNOYED (A) you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or GUILTY (G) about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning, to steady your nerves, or to get rid of a hangover (use of alcohol as an EYE-OPENER [E] in the morning)?

- If you responded "yes" to at least two of these questions, you may be at risk for alcohol use disorder.

Primary care doctors should screen adults for alcohol use disorder, according to guidelines from the U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Health care providers can give people identified at risk brief behavioral counseling interventions to help them address their drinking.

Oral naltrexone (ReVia, generic) and acamprosate (Campral, generic) are effective medications for treating alcohol use disorders. Disulfiram (Antabuse, generic) is an aversion medication that may be indicated in select cases of alcohol use disorder.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) refer to excessive drinking behaviors that can create dangerous conditions for an individual and others. Alcohol use disorders are classified according to their severity as mild, moderate, and severe AUD.

People with AUD may experience the following symptoms related to their drinking:

- Craving, or a strong urge to drink.

- Loss of control, or not being able to limit consumption of alcohol once they start drinking.

- Tolerance, or the need for increased amounts of alcohol to produce the same effect.

- Withdrawal symptoms (nausea, sweating, irritability, and tremors) when the effects of alcohol are wearing off.

AUD often results in adverse outcomes such as:

- Failure to fulfill work, school, or personal obligations.

- Recurrent use of alcohol in potentially dangerous situations (such as driving).

- Continued use in spite of harm being done to social or personal relationships.

- Continued use in spite of health problems caused or aggravated by alcohol.

AUD can lead to liver, cardiovascular, and neurological problems. Drinking too much alcohol can increase the risk for infectious disease and for developing certain cancers. Pregnant women who drink alcohol in any amount may harm the fetus.

In the United States, the definition of 1 drink is 14 grams of pure alcohol, which is equivalent to:

- A 12 ounces (350 mL) can of regular beer

- A 5 ounces (150 mL) glass of table wine

- A 1.5 ounces (44 mL) shot of hard liquor

Other countries define a standard drink differently, for example, 8 grams of alcohol in the U.K or 19.75 grams in Japan. A person is affected by the amount of alcohol consumed, not the type. Beer and wine are not "safer" than hard liquor; they simply contain less alcohol per ounce.

Moderate drinking:

- Up to 2 drinks per day for men

- Up to 1 drink per day for women

Low risk drinking:

- No more than 4 drinks on any single day and no more than 14 drinks per week for men

- No more than 3 drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week for women

For some people, such as women at risk for breast cancer, even light drinking may be harmful. Even small amounts of alcohol should be avoided in certain circumstances, such as before driving a vehicle or operating machinery, if you are pregnant or trying to become pregnant, when taking medications that may interact with alcohol, or if you have a medical condition that may be worsened by drinking.

Heavy (at-risk) drinking:

- More than 4 drinks in a day or 14 drinks per week, for men

- More than 3 drinks in a day or 7 drinks per week, for women

Binge drinking is a pattern of drinking that brings blood alcohol levels to 0.08 g/dL. Typically this occurs after consuming 5 drinks (for men) or 4 drinks (for women) in less than 2 hours.

Causes

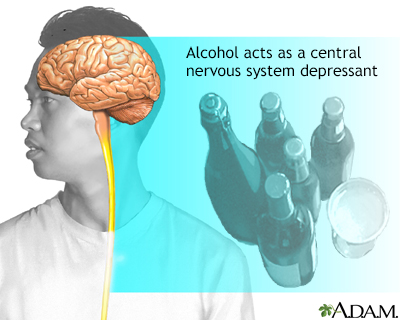

The chemistry of alcohol allows it to affect nearly every type of cell in the body, including those in the central nervous system, where alcohol acts as a neurotoxin. The long-term changes in brain function that allow it to adapt to the prolonged exposure to alcohol may also lead to the tolerance and withdrawal effects of alcohol that are associated with dependence. Genetic, psychological, and environmental factors affect the risk for AUD, and the time it takes to develop.

Alcohol alters brain function by interacting with many different chemical messengers in the brain (neurotransmitters). Specifically, alcohol affects the balance between "inhibitory" and "excitatory" neurotransmitters. This balance changes over time:

- Short-term alcohol use increases inhibitory neurotransmitters and suppresses excitatory neurotransmitters. In the short term, alcohol has a "depressant" effect. It causes the slowed-down and sluggish speech and movement patterns associated with being drunk. At the same time, alcohol increases pleasurable feelings, such as euphoria and a sense of being rewarded.

- Long-term alcohol use forces the brain to try to restore balance by decreasing inhibitory neurotransmitter activity and increasing excitatory neurotransmitter levels. This leads to tolerance: Increasing amounts of alcohol are required to produce a pleasurable high. Over the long term, tolerance can lead to addiction.

Genetic factors are significant in AUD and may account for about half of the total risk for a person becoming alcohol dependent. The role that genetics plays in AUD is complex and it is likely that many different genes are involved.

However, genes are not the sole determinant. Environment, personality, and psychological factors also play a strong role.

When an alcohol-dependent person tries to quit drinking, the brain seeks to restore what it perceives to be its equilibrium. The brain responds with depression, anxiety, and stress (the emotional equivalents of physical pain), which are produced by brain chemical imbalances. These negative moods continue to trigger people to return to drinking long after physical withdrawal symptoms have resolved. Emotional stress and social pressure also contribute to relapse.

Risk Factors

According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 86.4 percent of people in the United States ages 18 or older reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their lifetime, however only 8.4% men and 4.2% women in this age group had AUD.

There are many different risk factors for alcohol use disorders.

Alcohol use disorders are most common among people ages 18 to 29. In the United States, many young people drink alcohol and underage drinking is a serious public health problem. According to surveys, by age 18, about 60% teens have had at least one drink. People ages 12 to 20 often binge drink. Anyone who begins drinking in adolescence is at risk for developing AUD. The earlier in life a person begins drinking, the greater the risk.

People with a family history of alcohol use disorders are more likely to begin drinking before the age of 20 and to develop AUD later. Young people at highest risk for early drinking are those with a history of abuse, family violence, depression, and stressful life events.

Children, adolescents, and older people are generally more vulnerable to alcohol-related harm compared to other age groups.

Men have a greater risk than women for alcohol use disorders.

People with a family history of alcoholism are more likely to have a problem with alcohol disorders. Alcohol use disorders appear to be strongly heritable. The risk is significantly increased in first-degree relatives, especially father to son. The risk is further increased if the affected parent began drinking before age 25. Children who grow up in an alcoholic household where abusive behavior is common are also more likely to later develop problems with alcohol. According to NIAAA, more than 10% of U.S. children live with a parent with alcohol problems.

Different cultures and societies have different beliefs and expectations regarding drinking and what constitutes acceptable drinking behavior. AUD is not restricted to any specific socioeconomic group or class. Alcohol consumption is more prevalent in economically developed countries, where the availability of alcohol is greater, the cost is lower, and alcohol advertising is more aggressive. However, in any individual or group, lower socioeconomic status is linked with greater vulnerability to the harmful effects of alcohol use.

Overall, there is no difference in prevalence of AUD among African-Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanic-Americans. Some population groups, such as Native Americans, have an increased risk for AUD while others, such as Jewish and Asian Americans, have a lower risk. These differences may be due in part to genetic susceptibility and cultural factors.

Alcohol and other substance abuse are very common among people who have mental health problems. Depression is a very common psychiatric problem in people with AUD. AUD is also prevalent in people with anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or conduct disorders may have a higher risk for AUD in adulthood.

Complications

AUD reduces life expectancy. The earlier that people begin drinking heavily, the greater their chances of developing serious illnesses later on in life. Alcohol is causally linked with over 50 diseases and contributes to 4% of the global burden of disease and 6% of all causes of death. In the United States, alcohol is the fourth leading preventable cause of death.

Heavy drinking is associated with earlier death. However, it is not just from a higher risk of the more common serious health problems, such as heart attack, heart failure, diabetes, lung disease, or stroke. Chronic alcohol consumption also leads to many problems that can increase the risk for death:

- Globally, around 3.3 million deaths result from harmful use of alcohol each year, according to the World Health Organization.

- People who drink regularly have a higher rate of death from injury, violence, or suicide.

- Alcohol overdose can lead to death. This is a particular danger for adolescents who binge drink.

- People with AUD who need surgery have an increased risk of postoperative complications, including infections, bleeding, reduced heart and lung functions, and problems with wound healing. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms after surgery may delay recuperation.

Studies suggest that long-term alcohol use may cause chemical changes in the brain that increase the risk for depression. There is an increased risk of suicide amongst people who abuse alcohol compared to non-drinkers. Alcohol is associated with impulsivity and can have a negative impact on important social relationships that otherwise might have been protective and reduced the suicide risk

Alcohol-induced liver disease (also called alcoholic liver disease) is a spectrum of liver disorders caused by excessive alcohol consumption. Alcohol-induced liver disease includes:

- Fatty liver

- Alcoholic hepatitis

- Alcoholic cirrhosis

Fatty liver

An accumulation of fat inside liver cells. It is the most common type of alcohol-induced liver disease and can occur even with moderate drinking. Symptoms include an enlarged liver with pain in the upper right quarter of the abdomen. Fatty liver can be reversed once the person stops drinking. Fatty liver can also develop without drinking, especially in people who are obese or have type 2 diabetes.

Alcoholic hepatitis

Inflammation of the liver that develops from heavy drinking. Symptoms include fever, jaundice (yellowing of the skin), right-side abdominal pain, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting. Mild cases may not produce symptoms. People who are diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis must stop drinking. Those who continue to drink may go on to develop cirrhosis and liver failure.

Alcohol use disorder also increases the risks for chronic hepatitis B and C, which are associated with increased risks for cirrhosis and liver cancer. People with AUD should be immunized against hepatitis B. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

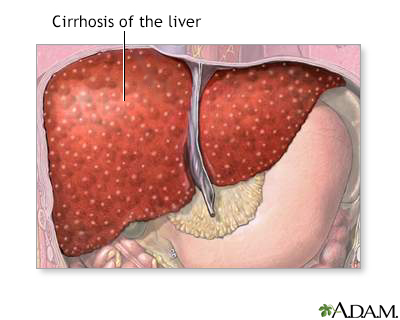

Cirrhosis

A chronic liver disease that causes damage to liver tissue, scarring of the liver (fibrosis, nodular regeneration), and progressive decrease in liver function.

Excessive alcohol use is the leading cause of cirrhosis in the United States. Consequences of a failing liver include excessive fluid in the abdomen (ascites), increased pressure in certain blood vessels (portal hypertension), life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding (such as from esophageal varices), and brain function disorders (hepatic encephalopathy). Cirrhosis can eventually be fatal.

Between 10% to 20% of people who drink heavily develop cirrhosis.

In 2015, alcohol-related liver disease was the primary cause of more than 1 in 5 liver transplants in the United States.

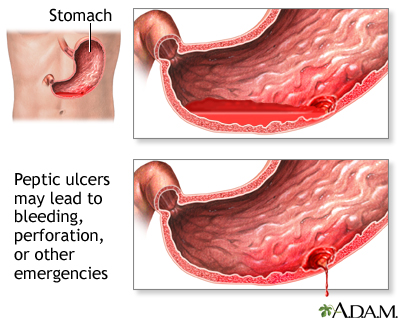

AUD causes many problems in the gastrointestinal tract. Violent vomiting can produce tears in the junction between the stomach and esophagus. Heavy drinking increases the risk for ulcers, particularly in people taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin or ibuprofen. It can also lead to swollen veins in the esophagus, (varices), and to inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) and bleeding.

Alcohol can contribute to serious acute and chronic inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) in people who are susceptible to this condition. There is some evidence of a higher risk for pancreatic cancer in people with AUD, although this higher risk may occur mainly in people who are also smokers.

Moderate amounts (1 to 2 drinks a day) of alcohol may modestly improve some heart disease risk factors, such as increasing HDL (good) cholesterol levels and preventing clot formation. However, there is no definitive proof that light-to-moderate drinking improves heart and overall health, and the American Heart Association does not recommend drinking alcoholic beverages to reduce cardiovascular risk.

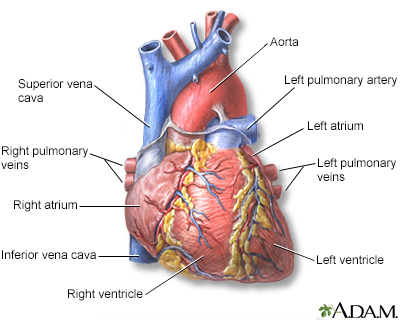

Excessive drinking clearly has negative effects on heart health. Alcohol is a toxin that damages the heart muscle. In fact, heart disease is one of the leading causes of death for people with AUD. Heavy drinking raises levels of triglycerides (unhealthy fats) and increases the risks for high blood pressure, heart failure, and stroke. In addition, the extra calories in alcohol can contribute to obesity, a major risk factor for diabetes and many heart problems.

Heavy alcohol use increases the risks for mouth, throat, esophageal, gastrointestinal, liver, breast, and colorectal cancers. Even light drinking can increase the risk of breast cancer. Women who are at risk for breast cancer should consider not drinking at all.

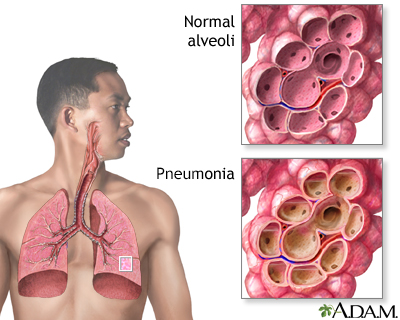

Over time, excessive alcohol consumption can suppress the immune system response to infections. AUD is associated with increased risk for respiratory infections, especially bacterial pneumonia and tuberculosis, as well as hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections. AUD also increases the severity and duration of infectious diseases. People who are alcohol dependent should get an annual pneumococcal pneumonia vaccination.

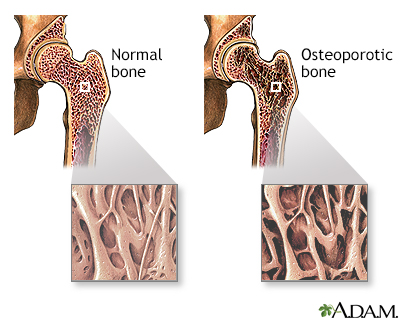

Severe alcohol use disorder is associated with osteoporosis (loss of bone density), muscular deterioration, skin sores, and itching.

Sexual Function and Fertility

AUD increases levels of the female hormone estrogen and reduces levels of the male hormone testosterone. Imbalances in these hormones may lead to erectile dysfunction and enlarged breasts in men, and infertility in women. Other increased risks for women include menstruation problems such as absent menstrual periods and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Drinking During Pregnancy

Even moderate amounts of alcohol can have damaging effects on a developing fetus, including low birth weight and an increased risk for miscarriage. High amounts can cause fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition associated with poor growth and developmental delay. The risk for fetal alcohol syndrome is increased depending on when alcohol exposure occurs during pregnancy, the pattern of drinking, and how frequently alcohol consumption occurs.

A regular beer contains about 153 calories, a glass of table wine contains 125 calories, and a shot of hard liquor has 97 calories. Drinking alcohol in excess contributes to excess calories, which can lead to weight gain Obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes.

People with diabetes should be aware that alcohol consumption can cause hypoglycemia (low blood sugar). If you choose to consume alcohol, do so in moderation and only drink on a full stomach. Be sure to check your blood glucose level before drinking to make sure it is not low.

Alcohol is associated with insomnia and other sleep disorders. Although alcohol may hasten falling asleep, it causes frequent awakenings throughout the night. Alcohol disrupts sleep patterns by reducing sleep quality and the amount of time spent in deep sleep. People with alcohol-use disorders who stop drinking often continue to experience sleep problems for some time.

Both short- and long-term alcohol use adversely affects the brain and causes cognitive impairment, including lapses in memory, attention, and learning abilities. Short-term heavy drinking can cause blackouts. Long-term alcohol use can physically shrink the brain. Depending on length and severity of alcohol abuse, neurologic damage may or may not be permanent.

Recent high alcohol use (within the last 3 months) is associated with some loss of verbal memory and slower reaction times. Over time, chronic alcohol abuse can impair so-called "executive functions," which include problem solving, task flexibility, short-term memory, and attention. These problems are usually mild to moderate and can last for weeks or even years after a person quits drinking.

Chronic alcohol use can cause vitamin and mineral deficiencies for several reasons. People with AUD often do not eat well and are poorly nourished. In addition, alcohol interferes with the absorption and metabolism of nutrients. Chronic heavy drinking is associated with deficiencies in vitamin A, C, D, E, K, and the B vitamins, as well as minerals such as calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc. Deficiencies in vitamin B pose particular health risks:

- Thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency is associated with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, also called alcoholic encephalopathy, which causes permanent brain damage.

- Folate (vitamin B9) deficiency can cause severe anemia. Deficiencies during pregnancy can lead to birth defects in the infant.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency can lead to pernicious anemia and neurological problems.

Alcohol interacts with nearly all medications. The effects of many medications are strengthened by alcohol, while others are inhibited. Of particular importance is alcohol's reinforcing effect on anti-anxiety drugs, sedatives, sleep medications, antidepressants, and antipsychotic medications.

Alcohol also interacts with many drugs used by people with diabetes. It interferes with drugs that prevent seizures or blood clotting. It increases the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding in people taking aspirin or other nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen and naproxen.

In general, people who require medication should use alcohol with great care, if at all.

Alcohol and nicotine addiction share common genetic factors, which may partially explain why people with alcohol problems are often smokers. People who drink and smoke compound their health problems. In fact, some studies indicate that people who drink and smoke are more likely to die of smoking-related illnesses than alcohol-related conditions. Abuse of other drugs is also common among people with alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol plays a large role in accidents, suicide, and crime:

- Alcohol plays a major role in nearly one third of all automobile fatalities. Fewer than 2 drinks can impair the ability to drive.

- Alcohol-related automobile accidents are one of the leading causes of death in young people.

- Alcohol is significantly implicated in crimes involving rape, assault, and murder.

- Alcohol abuse is a common problem in homes with domestic violence and child abuse.

- AUD is frequently present in people who commit suicide.

Health care providers may overlook alcohol use disorder when evaluating older people, mistakenly attributing the signs of alcohol abuse to the normal effects of the aging process. But alcohol abuse is a serious concern for older people. Some older people have struggled with alcohol abuse or dependence throughout their lives. Others may turn to alcohol later in life to cope with loss (death of a spouse), loneliness, and depression.

Alcohol affects the older body differently. It takes fewer drinks to become intoxicated, and older organs can be damaged by smaller amounts of alcohol than those of younger people. Alcohol can worsen many conditions common in older populations (diabetes, memory loss, osteoporosis, and high blood pressure). It can increase the risk for falls. Also, many of the medications prescribed for older people interact adversely with alcohol.

Although not traditionally thought of as a medical problem, hangovers have significant consequences. Hangovers can impair job performance, increasing the risk for mistakes and accidents. Hangovers are generally more common in light-to-moderate drinkers than heavy and chronic drinkers, suggesting that binge drinking can be as threatening as chronic drinking. Any man who drinks more than 5 drinks or any woman who has more than 3 drinks at one time is at risk for a hangover.

Symptoms

You may be experiencing symptoms of AUD if you experience:

- Craving, or a strong urge to drink.

- Loss of control, or not being able to limit consumption of alcohol once you start drinking.

- Tolerance, or the need for increased amounts of alcohol to produce the same effect.

- Withdrawal symptoms (nausea, sweating, irritability, and tremors) when the effects of alcohol are wearing off.

Alcohol use disorders can develop insidiously. Eventually, alcohol dominates thinking, emotions, and actions and becomes the primary means through which a person with AUD deals with social relations, work, and life.

Diagnosis

According to the U.S. National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), to be diagnosed with AUD, an individual must meet certain criteria described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), issued by the American Psychiatric Association. According to the current edition of DSM (DSM-5), AUD is diagnosed and classified as mild, moderate or severe based on the answers to the following 11 questions related to alcohol use within the past year.

In the past year, have you:

- Had times when you ended up drinking more, or longer, than you intended?

- More than once wanted to cut down or stop drinking, but couldn't?

- Spent a lot of time drinking, being sick, or getting over other aftereffects of drinking?

- Wanted a drink so badly that you couldn't think of anything else?

- Found that drinking, or being sick from drinking, often interfered with taking care of your home or family, or caused job or school troubles?

- Continued to drink even though it was causing trouble with your family or friends?

- Given up or cut back on activities that were important, interesting, or pleasant to you, in order to drink?

- More than once gotten into situations while drinking or after drinking that increased your chances of getting hurt (such as driving, swimming, using machinery, walking in a dangerous area, or having unsafe sex)?

- Continued to drink even after having had a memory blackout or even though it was making you feel depressed or anxious or adding to another health problem?

- Had to drink much more than you once did to get the effect you want or found that your usual number of drinks had much less effect as before?

- Found that when the effects of alcohol were wearing off, you had withdrawal symptoms such as shakiness, restlessness, trouble sleeping, nausea, sweating, a racing heart, a seizure, or sensed things that were not there?

AUD is diagnosed in the presence of at least 2 of these 11 symptoms. AUD is classified as mild (2 to 3 symptoms), moderate (4 to 5 symptoms) or severe (6 or more symptoms).

Sometimes a person can recognize that alcohol is causing problems, and will seek the advice of a health care provider on their own. Other times, family, friends, or co-workers may be ones who must encourage the person to discuss their drinking habits with their provider. According to the CDC, only 1 in 6 American adults, including binge drinkers, have ever discussed their alcohol use with a health care professional.

Guidelines recommend that primary care doctors routinely screen for alcohol misuse during office visits with their patients. Screening may begin with a simple question: "Do you sometimes drink alcoholic beverages?"

A provider who suspects alcohol abuse should ask the person questions about current and past drinking habits to distinguish low-risk from at-risk (heavy) drinking. Screening tests for alcohol problems in older people should check for possible medical problems or medications that might place them at higher risk for drinking than younger individuals.

A number of short screening tests are available, which people can even take on their own. You can take a free and anonymous screening test online -- www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/How-much-is-too-much/whats-the-harm/what-Are-Symptoms-Of-An-alcohol-Use-Disorder.aspx.

AUDIT Test

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is specifically recommended as a screening tool by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. It is designed to identify people at risk for heavy (hazardous) drinking. A short 3-question version asks people how often in the past year they drink alcohol, how many drinks they typically have on a day when they do consume alcohol, and how often they have had 6 or more drinks on one occasion.

The full 10-question version of AUDIT asks:

- How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?

- How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?

- How often do you have 6 or more drinks on that occasion?

- How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?

- How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking?

- How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking?

- How often during the last year have you needed an alcoholic drink first thing in the morning to get yourself going after a night of heavy drinking?

- How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking?

- Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking?

- Has a relative, friend, doctor, or another health professional expressed concern about your drinking or suggested you cut down?

CAGE Test

The CAGE test is an acronym for the following questions and is one of the quickest screening tests. It asks:

- Have you ever felt you should CUT (C) down on your drinking?

- Have people ANNOYED (A) you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or GUILTY (G) about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning, to steady your nerves, or to get rid of a hangover (use of alcohol as an EYE-OPENER [E] in the morning)?

Two "yes" responses indicate a positive test and warrant further investigation.

CRAFFT Test

The CRAFFT test is a behavioral health screening tool for use with children under the age of 21 developed to screen adolescents for high risk alcohol and other drug use disorders simultaneously.

Other Screening Tests

Other screening tests include the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST), the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS), and the T-ACE.

The provider will perform a physical examination and ask about family and medical history. The provider may order tests to check for health problems that are common in people who use alcohol. These tests may include:

- Blood alcohol level (This shows if you have recently been drinking alcohol. It does not diagnose AUD.)

- Urine toxicology screen (which includes alcohol)

- Complete blood count

- Liver function tests

Some blood tests use biologic markers to identify organ damage associated with chronic heavy alcohol use:

- Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) assists with iron transport in the body. It is a marker for heavy drinking and can be helpful in monitoring progress towards abstinence.

- Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is a liver enzyme that is very sensitive to alcohol. It can be elevated after moderate alcohol intake and in chronic alcohol use disorder.

- Aspartate (AST) and alanine aminotransaminases (ALT) are liver enzymes that are markers for liver damage.

- Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) refers to the size of red blood cells. High levels of MCV are common in people with AUD.

Treatment

There are many options for treatment for alcohol use disorders. They depend in part on the severity of the drinking problem. A primary care physician can evaluate the drinking pattern and help craft a treatment plan for a patient. Additionally, primary care physicians can evaluate the overall health of people with AUD and determine whether medications are appropriate.

Treatment for AUD may include:

- Behavioral treatment

- Medications

- Mutual support groups

Guidelines recommend that primary care doctors do brief behavioral counseling interventions for people who show signs of risk to help them reduce or stop their drinking. Your health care provider may give you an action plan for working on your drinking, ask you to keep a daily diary of how much alcohol you consume, and recommend target goals for your drinking. Your provider may recommend anti-craving or aversion medication and also refer you to other health care professionals for substance abuse services.

Treatment of alcohol use disorder is often complicated and compounded by accompanying medical illnesses such as high blood pressure, stomach ulcers, and nutritional deficiencies. Psychiatric illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder are also common. These co-existing conditions must be addressed and treated.

The goal of long-term treatment for AUD varies from person to person and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Although, people who achieve total abstinence have better survival rates, mental health, and relationships, than those who continue to drink or relapse.

Abstinence can be challenging to attain. Most people with AUD can benefit from some form of treatment and of those who do, about one third report no further symptoms one year later. Even merely reducing alcohol intake can lower the risk for alcohol-related medical problems. Current research efforts in the area of personalized medicine are aimed at identifying genes or other factors that can predict the response of an individual to a particular treatment for AUD.

The choice of a treatment program or facility is based on several considerations, such as:

- The kind of treatments provided

- Whether they are tailored to the individual

- Whether success is measured

- How relapse is handled

Other factors include cost and insurance coverage. A primary consideration is whether the person will need medical supervision during withdrawal (detoxification).

Some studies have reported better success rates with inpatient treatment of people with AUD. However, other studies strongly suggest that AUD can be effectively treated in outpatient settings.

Residential (inpatient) centers provide intensive care in a safe and structured facility. A typical stay at an inpatient center can last from 1 to 3 months. During this time, the person undergoes detoxification and, once stabilized, then begins daily treatment for recovery. Therapeutic approaches may include behavioral therapy, medications, education, counseling, and mutual support groups. Mental health disorders and medical conditions are also addressed.

Outpatient treatment centers provide similar therapies but the person lives at home and attends an alcohol recovery program several times a week.

The current approach to outpatient treatment often uses "medical management," a disease management approach that is used for chronic illnesses such as diabetes. With medical management, people receive regular 20-minute sessions with a provider. The provider monitors the person's medical condition, medication, and alcohol consumption.

Once people complete and inpatient or outpatient program, they need help to maintain sobriety or moderation. Relapse is common in the first year after treatment. "Aftercare" programs help reduce the risk for relapse. These programs can range from mutual support groups to sober-living or transitional houses.

About half of people who have alcohol-use disorders experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop drinking. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms occur within 6 to 12 hours after the last drink, but can persist for many days. Symptoms usually peak during the second day of abstinence and improve by the fifth day.

Withdrawal symptoms can include:

- Sweating

- Shaking

- Headaches

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Nausea and vomiting

While uncommon, severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal can include seizures, hallucinations, and delirium tremens. Delirium tremens is a potentially life-threatening condition marked by severe mental and nervous system changes.

A provider should medically manage or supervise the detoxification process. Detox may be done on an inpatient or outpatient basis depending on the person's age, health condition, and severity of symptoms. Anti-anxiety medications such as benzodiazepines may be administered to help relieve withdrawal symptoms.

Detoxification does not cure the craving for alcohol but it is the first step for recovery. People who complete detox can then begin other treatments (counseling, medication) to address their addiction.

Medications

Three drugs are specifically approved to treat alcohol use disorders:

- Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol, generic)

- Acamprosate (Campral, generic)

- Disulfiram (Antabuse, generic)

Naltrexone and acamprosate are anticraving drugs. Disulfiram is an aversion drug. Other medications, which are not approved for alcohol disorder treatment, may be prescribed off-label.

Anticraving drugs reduce the urge to drink and help in maintaining abstinence.

Evidence suggests that acamprosate and oral naltrexone are very effective for preventing craving and helping maintain abstinence. Researchers are also studying whether they can be used in combination for people who do not respond to single drug treatment.

Naltrexone

Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol, generic) is an antagonist approved for the treatment of AUD. Naltrexone helps reduce alcohol dependence in the short term for people with moderate-to-severe AUD. ReVia, a pill that is taken daily by mouth, is the oral form of this medication. Vivitrol is a once-a-month injectable form of naltrexone. Studies suggest that oral naltrexone can help reduce heavy drinking and prevent relapse.

Naltrexone should be prescribed along with psychotherapy or other supportive medical management. The most common side effects are nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain, which are usually mild and temporary. Other side effects include headache and fatigue. High doses can cause liver damage. The drug should not be given to anyone who has used narcotics within 7 to 10 days.

It is important to take the pill form of naltrexone (Revia, generic) on a daily basis. Because many people have difficulty sticking to this daily regimen, a monthly injection of vivitrol is another option. Injectable naltrexone can cause skin reactions and infections. People should monitor the injection site for pain, swelling, tenderness, bruising, or redness and contact their doctors if these symptoms do not improve within 2 weeks.

Naltrexone does not work in all people. Some studies suggest that people with a specific genetic variant may respond better to the drug than those without the gene.

Acamprosate

Acamprosate (Campral, generic) is another anti-craving medication. It appears to work by restoring the balance of GABA and glutamate neurotransmitters. Studies indicate that it reduces the frequency of drinking, helps to maintain abstinence, and, in combination with psychotherapy, improves quality of life even in people with severe alcohol dependence.

This medication may cause occasional diarrhea, nausea, and headache. People with kidney problems should use acamprosate cautiously. Acamprosate may increase the risk for suicide.

Disulfiram

Aversion medications have properties that interact with alcohol to produce distressing side effects. Disulfiram (Antabuse, generic) causes flushing, headache, nausea, and vomiting if a person drinks alcohol while taking the drug. The symptoms can be triggered after drinking half a glass of wine or half a shot of liquor and may last from half an hour to 2 hours, depending on dosage of the drug and the amount of alcohol consumed.

Overdose can be dangerous, causing low blood pressure, chest pain, shortness of breath, and even death.

Research suggests that disulfiram is not that effective for reducing heavy alcohol consumption. Anti-craving medications, such as acamprosate or naltrexone, are now more commonly used.

Behavioral Treatment

Behavioral treatments are led by health care professionals and have been proven as effective. Standard forms of psychotherapy for alcohol use disorders include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Motivational enhancement therapy

- Marital and family counseling

- Brief interventions

Common elements provided by behavioral treatments are:

- Providing counseling on skills development to reduce or stop drinking

- Building a strong social support system of family and friends

- Setting reachable goals

- Preventing relapse by developing coping strategies for relapse triggers

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) uses a structured one-on-one counseling approach. People are given instruction and homework assignments intended to improve their ability to cope with basic living situations, control their behavior, and change the way they think about drinking.

A CBT therapist may recommend:

- Keeping a diary of your drinking experiences and identifying risky situations and triggers that prompt drinking.

- Skills to help cope when exposed to "cues" (places or circumstances that provoke the desire to drink).

- Activities that can replace drinking.

CBT may be especially effective when used in combination with opioid antagonists, such as naltrexone. CBT that addresses AUD and depression is an important treatment for people with both conditions.

Motivational enhancement therapy is a short-term form of behavioral treatment focused on gaining motivation to seek and maintain therapy. The therapist may help devise a plan for changing drinking behaviors and developing the confidence and skills necessary for implementing the plan.

Marital and family counseling integrates the spouse and other family members into the treatment plan, by using their support and resources, while at the same time improving family relationships. There is a better chance for maintenance of abstinence when strong family support is present.

Brief interventions can be conducted on an individual or small group basis. Typically, these interventions involve an evaluation of the drinking behavior and risks and providing brief counseling on treatment goals and options.

Medications such as naltrexone or acamprosate may be administered together with behavioral therapy. A large clinical study called COMBINE compared the effectiveness of drug therapy, medical management, and combined behavioral intervention (CBI), alone or as a combination in the treatment of alcohol use disorder. The study concluded that although all of these options were effective, therapies that pair medical management with medications or with CBI were the most effective. CBI combines elements from other psychotherapy treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement therapy, and mutual support groups.

Mutual support groups offer supervised peer support to people with AUD. Group sessions are not led by health professionals and, due to the anonymous nature of many of these organizations (such as Alcoholics Anonymous), the effectiveness of their treatment programs by themselves is unknown. However, when used in combination with treatment led by health professionals, mutual support groups can be a valuable tool in achieving and maintaining treatment goals for people with AUD. Some of these are structured as 12-steps programs and based on religious or spiritual practices, while others emphasize rational or scientific approaches to recovery. The goals of mutual support groups range from total abstinence to moderation, and their tolerance for relapse may also vary. Examples of mutual support groups include:

- Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)

- Moderation Management

- SMART Recovery

- Secular Organization for Sobriety

- Women for Sobriety

- Al-Anon Family Group (for family and friends)

People with AUD often have insomnia and other sleep problems, which can last months to years after abstinence. Sleep disturbances may even influence relapse. Available therapies include sleep hygiene, bright light therapy, meditation, relaxation methods, and other nondrug approaches. Many of the medications for insomnia are not recommended for people with AUD because they can interact dangerously with alcohol.

Some people try other methods, such as acupuncture, hypnosis, or relaxation techniques. Such approaches are not harmful, although it is not clear how effective they are.

Resources

- FASD United -- fasdunited.org/

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcohol -- www.niaaa.nih.gov

- Rethinking Drinking: Alcohol and Your Health -- rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration -- www.samhsa.gov

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence -- www.ncaddesgpv.org

References

Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD008537. PMID: 21678378 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21678378.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Bommersbach TJ, Lapid MI, Rummans TA, Morse RM. Geriatric alcohol use disorder: a review for primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(5):659-666. PMID: 25939937 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25939937.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fact Sheets - Alcohol use and your health. www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm. Updated December 30, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020.

Connor JP, Haber PS, Hall WD. Alcohol use disorders. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):988-998. PMID: 26343838 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26343838.

Conway KP, Swendsen J, Husky MM, He JP, Merikangas KR. Association of lifetime mental disorders and subsequent alcohol and illicit drug use: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):280-288. PMID: 27015718 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27015718.

Fuster D, Samet JH. Alcohol use in patients with chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(13):1251-1261. PMID: 30257164 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30257164.

Kelly JF, Renner JA. Alcohol-related disorders. In: Stern TA, Fava M, Wilens TE, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Psychopharmacology and Neurotherapeutics. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 15.

Kranzler HR, Soyka M. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorder: A review. JAMA. 2018;320(8):815-824. PMID: 30167705 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30167705.

Leggio L, Lee MR. Treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Am J Med. 2017;130(2):124-134. PMID: 27984008 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27984008.

O'Connor EA, Perdue LA, Senger CA, et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: An updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [Internet]. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018 Nov. Report No.: 18-05242-EF-1. PMID: 30525341 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30525341.

O'Connor PG. Alcohol use disorders. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 30.

Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. PMID: 24967831 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24967831.

Sudakin D. Naltrexone: Not just for opioids anymore. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(1):71-75. PMID: 26546222 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26546222.

Winslow BT, Onysko M, Hebert M. Medications for alcohol use disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(6):457-465. PMID: 26977830 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26977830.

WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. www.who.int/en. Accessed August 15, 2019.

Reviewed By: Ryan James Kimmel, MD, Medical Director of Hospital Psychiatry at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. Editorial update on 01-21-2020.