Urinary incontinence - InDepth

Highlights

Types of Urinary Incontinence

There are many types of urinary incontinence. The main types are:

- Stress incontinence is triggered by activities (coughing, sneezing, laughing, running, or lifting) that apply pressure to a full bladder. Stress incontinence is very common among women who have given birth. It can also affect men who have had surgical procedures for prostate disease, especially cancer.

- Urge incontinence. The main symptom of overactive bladder is marked by an overwhelming and sudden need to urinate. Frequent urination is also a symptom of overactive bladder. There are many causes of urge incontinence, including medical conditions (benign prostatic hyperplasia, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, stroke, and spinal cord injuries), bladder infections or obstructions, and the aging process. It can also happen for unknown reasons.

- Mixed incontinence. Some people have a combination of stress and urge urinary incontinence.

Treatment of Urinary Incontinence

Treatment options for urinary incontinence depend on the type of incontinence and the severity of the condition. Treatments include:

- Lifestyle Changes. Significant weight gain can weaken pelvic floor muscle tone, leading to urinary incontinence. Losing weight through a healthy diet and exercise is important. Regulating the time you drink fluids, reducing fluid, and avoiding alcohol and caffeine are also helpful.

- Behavioral Techniques. Pelvic floor exercises (Kegel exercises) can help strengthen the muscles of the pelvic floor that support the bladder and close the sphincter. Bladder training can help patients learn to delay urination.

- Medications. Anticholinergic drugs, such as oxybutynin (Ditropan, Oxytrol) and tolterodine (Detrol), are the medications mainly used to treat urge incontinence. There are other available medications as well.

- Surgery. Several surgical procedures are available to treat stress urinary incontinence and urge urinary incontinence.

The American Urological Association's guidelines for managing overactive bladder emphasize that behavioral therapies and lifestyle changes should be the first treatment approaches.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence is the inability to control urination. It may be temporary or permanent and can result from a variety of problems in the urinary tract.

The main types of urinary incontinence are:

- Stress incontinence, which is leakage of urine triggered by effort or exertion.

- Urge incontinence, which is leakage of urine with a sudden and urgent need to urinate.

- Mixed incontinence, which includes both stress and urge types.

There are also other types of urinary incontinence. Overflow incontinence results from obstruction or chronic urinary retention (inability to empty the bladder), which causes urine to spill out of the blocked or non-functioning bladder. It can be seen in people with an enlarged prostate and those who have bladder nerve damage (neurogenic bladder) that impairs the bladder muscles' ability to contract. Overflow incontinence can be caused by pelvic surgery or conditions such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and spinal injury.

Functional incontinence refers to bladder difficulties experienced by patients who have a normal urinary system but have mental or physical disabilities that impair their mobility and keep them from getting to the bathroom in a timely fashion.

Because incontinence is a symptom, rather than a disease, it is often hard to determine the cause. In addition, a variety of conditions may be the cause.

Normal Urination

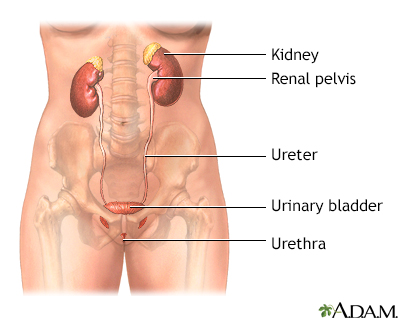

The urinary system helps to maintain proper water and salt balance throughout the body:

- The process of making urine begins in the two kidneys, which filter blood and eliminate water and waste products to produce urine.

- Urine flows out of the kidneys into the bladder through two long tubes called ureters.

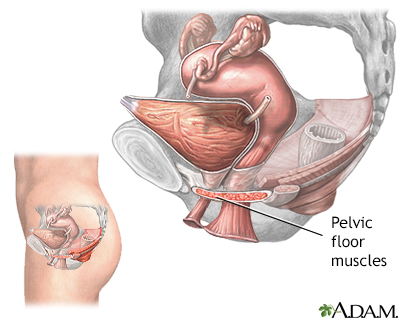

- The bladder is the organ that acts as a reservoir for urine. It is lined with a tissue membrane and enclosed in a powerful muscle called the detrusor. The bladder rests on top of the pelvic floor. This is a muscular structure at the base of the pelvis.

- The bladder stores the urine until it is eliminated from the body via a tube called the urethra, which is the lowest part of the urinary tract. (In men it is enclosed in the penis. In women it leads directly out.)

- The transition between the bladder and the urethra is called the bladder neck. Strong muscles called sphincter muscles encircle the bladder neck (the smooth internal sphincter muscles) and urethra (the fibrous external sphincter muscles).

The Process of Urination

The process of urination depends on a combination of automatic and voluntary muscle actions. There are two phases: the emptying phase and the filling and storage phase.

The Filling and Storage Phase

When a person has completed urination, the bladder should be empty. This triggers the filling and storage phase, which includes both automatic and voluntary actions.

- Automatic Actions. The automatic signaling process in the brain relies on a pathway of nerve cells and chemical messengers (neurotransmitters) called the cholinergic and adrenergic systems. Important neurotransmitters include acetylcholine and noradrenaline. The adrenergic pathway signals the detrusor muscle surrounding the bladder to relax. As the muscles relax, the bladder expands and allows urine to flow into it from the kidney. As the bladder fills to its capacity (about 8 to 16 ounces or 240 to 480 milliliters of fluid) the nerves in the bladder send back signals of fullness to the spinal cord and the brain.

- Voluntary Actions. As the bladder swells, the person becomes conscious of a sensation of fullness. In response, the individual holds the urine back by voluntarily contracting the external sphincter muscles, the muscle group surrounding the urethra. These are the muscles that children learn to control during the toilet training process.

When appropriate, urination (the emptying phase) begins.

The Emptying Phase

This phase also involves automatic and conscious actions.

- Automatic Actions. When a person is ready to urinate, the nervous system initiates the voiding reflex. The nerves in the spinal cord (not the brain) signal the detrusor muscle to contract. At the same time, nerves tell the involuntary internal sphincter (a strong muscle encircling the bladder neck) to relax. With the bladder neck now open, the urine flows out of the bladder into the urethra.

- Voluntary Actions. Once the urine enters the urethra, a person consciously relaxes the external sphincter muscles, which allows urine to completely drain from the bladder.

The female and male urinary tracts are basically identical except for the length of the urethra.

Causes

Causes of Stress Urinary Incontinence

Stress urinary incontinence is involuntary leakage triggered by physical acts that apply pressure to a full bladder, such as:

- Coughing

- Sneezing

- Laughing

- High-impact exercise

- Lifting

- Walking, standing from a seated position, or bending over (in moderate-to-severe cases)

Stress incontinence occurs because the internal sphincter does not close completely. It can also be caused by weak pelvic floor muscles.

In women, stress incontinence is nearly always due to:

- Vaginal deliveries. Pregnancy and childbirth can strain and weaken the muscles of the pelvic floor, causing a condition called urethral hypermobility. In urethral hypermobility the urethra does not close properly. It is one of the main causes of stress incontinence.

- Excess weight. Increased pressure on the bladder from extra weight can predispose to stress urinary incontinence.

- Genetic. SUI may run in families. There may be a genetic predisposition.

- Injury from surgery or radiation. This can damage or weaken the bladder neck muscles.

In men, stress urinary incontinence is usually caused by prostate treatments that damage the sphincter muscles:

- Treatment for prostate cancer. Radical prostatectomy, the main surgical treatment for prostate cancer, nearly always causes some degree of incontinence for several months. Within a year after the procedure, most men regain continence, although some leakage may still occur. Radiation therapy can also cause temporary urinary incontinence, although less commonly than surgery.

- Treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is the standard treatment for severe BPH, also called enlarged prostate. Laser vaporization of the prostate is another form of treatment. Temporary stress incontinence may occur in the month following these procedures.

Urinary incontinence after prostate procedures can sometimes be a combination of urge and stress.

Causes of Urge Urinary Incontinence

Urinary urgency is the powerful and sudden need to urinate that is hard to delay. People may leak or dribble urine if they don't make it to the bathroom in time. This is called urinary urge incontinence.

Urge urinary incontinence occurs when the detrusor muscle, which surrounds the bladder, contracts inappropriately during the filling stage. When this happens, the urge to urinate cannot be voluntarily suppressed, even temporarily.

Urge urinary incontinence is a main symptom of overactive bladder (OAB), also referred to as detrusor instability or overactivity. In addition to urgency, other symptoms of OAB include frequent urination (more than 8 times over a 24-hour period) and waking up at night to urinate (nocturia).

Conditions that can cause urge incontinence include:

- Neurological conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, or spinal cord injury.

- Bladder infection or obstruction.

- Older age.

- In women, the drop in estrogen level that occurs during menopause can contribute to urge incontinence by thinning and shrinking vaginal tissue (vaginal atrophy).

- In men, the enlarged prostate associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) can cause urge incontinence.

Overactive bladder can sometimes have no known cause (idiopathic). Other possible factors that can worsen symptoms include anxiety, cold temperature, stress, caffeine and alcohol consumption, or a diet rich in bladder irritants (spicy or acidic foods).

As with stress incontinence, excess weight can contribute to urge incontinence.

Risk Factors

About 20 million American women and 6 million men have urinary incontinence or have experienced it at some time in their lives. The number, however, may actually be higher because many people are reluctant to discuss incontinence with their doctors.

Some of the main risk factors for urinary incontinence include:

- Female sex

- Older age

- Being overweight or obese

- Brain disorders (such as stroke, Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis)

- During pregnancy or history of one or more births

- Enlarged prostate or history of prostate surgery

- Nerve damage from diabetes

Sex

Urinary incontinence is far more common among women than men. This is because pregnancy and childbirth, menopause, and the anatomical shape of the female urinary tract all increase the risk for incontinence. For men, enlarged prostate and surgery to correct prostate problems are the main risk factors for urinary incontinence.

Age

As people age, the muscles in the bladder and urethra weaken. For women, the loss of estrogen that occurs with menopause can also cause weakening of the pelvic and urinary tissues. Age is the most important risk factor for urinary incontinence in men.

Pregnancy and Childbirth

Pregnancy and childbirth increase the risk for stress incontinence. Vaginal birth can cause pelvic prolapse, a condition in which pelvic muscles weaken and the pelvic organs (bladder, uterus) slip into the vaginal canal. Each vaginal delivery further increases the risk of urinary incontinence. Pelvic prolapse may be associated with urinary incontinence.

It is not clear if cesarean delivery helps prevent urinary incontinence.

Weight

Being overweight or obese is a major risk factor for all types of incontinence. The more you weigh, the greater the risk.

Lifestyle Factors

Diet

Acidic foods (citrus fruits, tomatoes, chocolate) and beverages (alcohol, caffeine) that irritate or overstimulate the bladder can increase the risk for incontinence. Spicy foods are also a problem. Excessive consumption of any type of fluid can create problems with incontinence but it's also important not to cut back on fluid too much. Drinking insufficient amounts of healthy fluids (water) can lead to dehydration, which in turn causes bladder irritation and worsens urinary incontinence.

Smoking

Smoking increases the risk for incontinence, especially in heavy smokers (more than a pack a day).

Exercise

High-impact exercise can trigger stress incontinence and urinary leakage.

Medical Conditions

Medical conditions associated with an increased risk for urinary incontinence include:

- Stroke and spinal cord injury

- Neurological disorders (such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson disease)

- Urinary tract infections

- Type 2 diabetes

- Kidney disease

- Constipation

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (enlarged prostate) and prostate cancer

- Depression

- Impaired mobility

Medications

Drugs can cause temporary incontinence.

- Alpha-adrenergic blockers, such as tamsulosin (Flomax) used for benign prostatic hyperplasia, can cause incontinence by over-relaxing the bladder muscles.

- Diuretics, used for high blood pressure, rapidly introduce high urine volumes into the bladder.

- Other medications that increase the risk for incontinence include sedatives, muscle relaxants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and antihistamines.

Complications

Emotional Effects

Urinary incontinence can have severe emotional effects. People may feel humiliated, isolated, and helpless about their condition. Incontinence can interfere with social and work activities. Depression is very common in women with incontinence. Incontinence also has emotional effects on men. A number of studies of people with prostate cancer suggest that incontinence can be a much more distressing side effect for men than erectile dysfunction (another side effect of prostate cancer treatment).

Disruption of Daily Life

To prevent wetness or odors, people with incontinence may need to alter their way of life. Running errands can become difficult and require advance planning for locating public bathrooms. This problem is particularly noticeable in those with urge incontinence who may need to quickly reach a bathroom in order to avoid large-volume spills.

Specific Effects of Incontinence in Older Adults

Incontinence is particularly serious in older adults:

- Older adults who are otherwise healthy may stop exercising because of leakage, and a lack of activity can increase their impairment.

- Incontinence can result in loss of independence and quality of life. It is a major reason for nursing home placement.

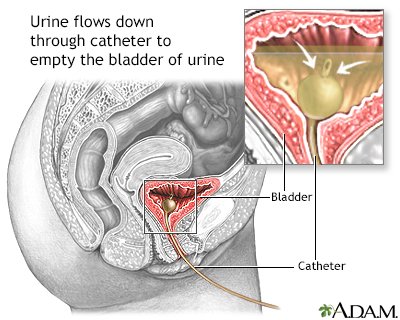

- Severe incontinence may require catheterization. This is the insertion of a tube that allows urine to continually pass into an external collecting bag. Catheters increase the risk for urinary tract infections and other complications.

- There is a strong association between urge incontinence and falls and injuries, which may be due in part to the rush to the toilet in the middle of the night. Keeping a pan or portable commode near the bed may prevent injuries, as well as improve sleep and general convenience.

Diagnosis

To diagnose urinary incontinence, your doctor will first ask about your medical history and lifestyle habits (including fluid intake). The doctor will conduct a physical examination to check for possible conditions that may be contributing to the problem. The doctor may collect a urine sample for analysis to check for infection.

If further evaluation is required, more specialized tests (urodynamic studies) may be performed. Urodynamic studies are used to test how well the bladder and urethra are performing. These tests include postvoid residual urine volume, cystometry, uroflowmetry, and electromyography. Imaging tests (video urodynamic tests) may also be used. A cystoscopy may also be done. It allows visualization of the inside of the urethra and bladder.

Medical History

The first step in the diagnosis of urinary incontinence is a detailed medical history. The doctor will ask questions about your present and past medical conditions and patterns of urination. Be sure to let your doctor know:

- When the problem began

- Frequency of urination

- Amount of daily fluid intake

- Use of caffeine or alcohol

- Frequency and description of leakage or urine loss, including activity at the time, sensation of urge to urinate, and approximate volume of urine lost

- Frequency of urination during the night

- Whether the bladder feels empty after urinating

- Pain or burning during urination

- Problems starting or stopping the flow of urine

- Forcefulness of the urine stream

- Presence of blood, unusual odor or color in the urine

- Prior surgeries, including pregnancies and deliveries, and other medical conditions

- Any medications being taken

Your doctor may ask questions to help distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence:

- During the last 3 months, have you leaked urine (even a small amount)?

- When did you leak urine? (During physical activity; when you could not reach the bathroom quickly enough; without physical activity or bladder urge.)

- When did you leak urine most often? (Physical activity; bladder urge; without or about equally with physical activity or bladder urge.)

Voiding Diary

You may find it helpful to keep a diary for 3 to 4 days before the office visit. This diary, sometimes referred to as a voiding diary or log, should be a detailed record of:

- Daily eating and drinking habits

- The times and amounts of urination, or going to the bathroom

For each incident of incontinence, the log should also detail:

- The amount of urine lost (your doctor may ask you to collect and measure urine in a measuring cup during a 24-hour period)

- Whether you had the urge to urinate

- Whether you were involved in physical activity at the time

Physical Examination

Your doctor will do a thorough physical examination, checking for abnormalities in the rectal, genital, and abdominal areas that may cause or contribute to the problem. The doctor may ask you to cough to check for stress urinary incontinence.

Urinalysis

The doctor may test a sample of your urine to see if a urinary tract infection (UTI) is causing your symptoms.

Postvoid Residual Urine Volume

The postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume test measures the amount of urine left after urination. Normally, about 50 mL or less of urine is left. More than 200 mL is abnormal and is a sign of urinary retention (overflow incontinence). Amounts between 50 and 200 ml may require additional tests for interpretation. A common method for measuring PVR is with a catheter, a soft tube that is inserted into the urethra within a few minutes of urination. Ultrasound, which is noninvasive, is also commonly used.

Cystometry

Cystometry, also called filling cystometry, measures how much urine the bladder can hold and the amount of pressure that builds up inside the bladder as it fills. Cystometry can be performed at the same time as the PVR test. The procedure uses several small catheters:

- A double-channel catheter is inserted through the urethra and into the bladder. It is used to fill the bladder with water and to measure pressure. Another catheter is inserted into the rectum or vagina, which is used to measure abdominal pressure.

- During the procedure, the patient informs the doctor about how the pressure is affecting the need to urinate.

- The patient may be asked to cough or strain to evaluate changes in bladder pressure and signs of leakage.

- Leakage of urine during coughing or straining is a sign of stress incontinence.

The detrusor muscle of a normal bladder will not contract during bladder filling. Severe contractions at low amounts of administered fluid will result in the feeling of urinary urgency. Stress incontinence is suspected when there is no significant increase in bladder pressure or detrusor muscle contractions during filling, but the person experiences leakage if abdominal pressure increases (such as with coughing or straining).

Uroflowmetry

To determine whether the bladder is obstructed, an electronic test called uroflowmetry measures the speed of urine flow. To perform this test, the patient urinates into a special measuring device.

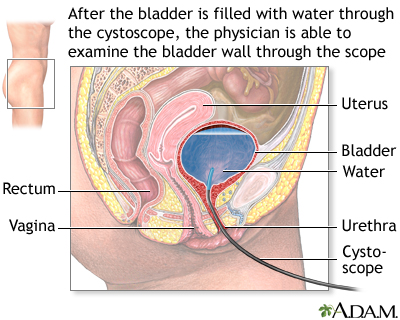

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy, also called urethrocystoscopy or cystourethroscopy, is performed to check for problems in the lower urinary tract, including the urethra and bladder. The doctor can determine the presence of structural problems, including enlargement of the prostate, obstruction of the urethra or bladder neck, anatomical abnormalities, or bladder stones. The test may also identify bladder cancer, causes of blood in the urine, and infection.

In this procedure, a thin tube with a light at the end (cystoscope) is inserted into the bladder through the urethra. The doctor may insert tiny instruments through the cystoscope to take small tissue samples (biopsies). Cystoscopy is typically performed as an outpatient procedure without the need for anesthesia. However, under some conditions the person may be given local, spinal, or general anesthesia.

Cystoscopy is a procedure that uses a flexible scope, which is inserted through the urethra into the urinary bladder. The doctor fills the bladder with water and inspects the interior of the bladder. The image seen through the cystoscope may also be viewed on a color monitor and recorded on videotape for later evaluation.

Multichannel Cystometry

Cystometry measures capacity and pressure in the bladder by evaluating how full the bladder gets before the patient feels the need to urinate. Multichannel cystometry is performed with several catheters. The first catheter is used to empty the bladder. A second catheter, which contains a pressure-measuring device, is inserted into the bladder. A third pressure-measuring catheter may be placed in the rectum or vagina.

Electromyography

Electromyography, also called electrophysiologic sphincter testing, is performed if the doctor suspects that nerve or muscle problems may be causing urinary incontinence. The test uses special sensors to measure electrical activity in the nerves and muscles around the sphincter. It evaluates the function of the nerves serving the sphincter and pelvic floor muscles, as well as the patient's ability to control these muscles.

Video Urodynamic Tests

Video urodynamic testing combines urodynamic tests with a special type of x-ray procedure called fluoroscopy. Fluoroscopy involves filling the bladder with a contrast dye and taking x-ray pictures so that the doctor can examine what happens when the bladder is filled and emptied.

Ultrasound is a painless test that uses sound waves to produce images. With ultrasound, the bladder is filled with warm water and a sensor is placed on the abdomen or inside the vagina to look for structural problems or other abnormalities.

Treatment

Treatment for temporary incontinence can be rapid, simple, and effective. If urinary tract infections are the cause, they can be treated with antibiotics. Any related incontinence will often clear up in a short time. Medications that cause incontinence can be stopped or changed to halt episodes.

Chronic incontinence may require a variety of treatments, depending on the cause. Treatment options are listed below in the order in which they are usually tried, from least-to-most invasive:

- Behavioral techniques, which include pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises and bladder training, are sometimes all a person needs to achieve continence. Behavioral techniques are helpful for both women and men. Devices may be used to strengthen muscles and prevent urine leakage. Lifestyle modifications include changes to diet and fluid intake.

- For overactive bladder symptoms, medications are tried next. Often, these involve anticholinergics. There are no effective medications to treat stress urinary incontinence.

- There are many effective surgical procedures for stress incontinence and for overactive bladder if there is no improvement with medications.

Lifestyle techniques to improve quality of life and hygiene are part of all treatments.

General Approach for Treating Specific Forms of Incontinence

Lifestyle measures, including dietary recommendations, bladder training, and continence aids, are useful for anyone with incontinence. Other treatments vary depending on whether the patient has stress or urge incontinence. In people who have both (mixed incontinence), the treatment usually is aimed at the predominant form.

Treating Stress Incontinence

The general goal for people with stress incontinence is to strengthen the pelvic muscles. Typical steps for treating women with stress incontinence are:

- Behavioral techniques and noninvasive devices, including Kegel exercises, weighted vaginal cones, and biofeedback.

- Devices and continence aids for blocking urine in the urethra (vaginal pessaries, adhesive pads, special tampons, and others).

- Surgery is an option if symptoms do not improve with noninvasive methods. There are many surgical techniques. Most are designed to support the bladder neck and urethra.

Treating Urge Incontinence

The goal of most treatments for urge incontinence is to reduce bladder hyperactivity. The following methods may be helpful:

- Behavioral methods and lifestyle modification.

- Medications (anticholinergics are the main type of drugs used).

- OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections into the bladder.

- Procedures that stimulate the pelvic floor or nerves in the tailbone (the sacral nerves) or a nerve in the foot (tibial nerve), that help retrain the bladder.

Behavioral Treatments

With the exception of functional incontinence, most cases of incontinence will almost always improve with behavioral techniques. There are a variety of methods, but the focus is usually on strengthening or retraining the bladder. These exercises are very effective for women, and also for men recovering from surgery for prostate cancer.

Combination of Kegel Exercises and Bladder Training

Pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises and bladder training are often recommended as the first-line approach for treating all forms of urinary incontinence. They can help to substantially improve symptoms in many people, including older people who have had the problem for years.

Pelvic Floor Muscle (Kegel) Exercises

Kegel exercises are designed to strengthen the muscles of the pelvic floor that support the bladder and close the sphincters.

Stress incontinence is an involuntary loss of control of urine that occurs at the same time abdominal pressure is increased, as in coughing or sneezing. It develops when the muscles of the pelvic floor have become weak.

Dr. Kegel first developed these exercises to assist women before and after childbirth, but they are very useful in helping to improve continence for both men and women.

The general approach for learning and practicing Kegel exercises is as follows:

- Because the muscles are sometimes difficult to isolate, the best method is to first learn while urinating. The person begins to urinate and then contracts the muscles in the pelvic area with the intention of slowing or stopping the flow of urine. Women should contract the vaginal muscles as well. They can detect this by inserting a finger inside the vagina. When the vaginal walls tighten, the pelvic muscles are being correctly contracted. People should place their hands on their abdomen, thighs, and buttocks to make sure there is no movement in these areas while exercising.

- An alternate approach is to isolate the muscles used in Kegel contractions by sensing then squeezing, and by lifting the muscles in the rectum that are used when passing gas. (Again, women should contract the vaginal muscles as well.)

- The first method is used for strengthening the pelvic floor muscles. The person slowly contracts and lifts the muscles and holds for 5 seconds, then releases them. There is a rest of 10 seconds between contractions.

- The second method is simply a quick contraction and release. The object of this exercise is to learn to shut off the urine flow rapidly.

- In general, people should perform 5 to 15 contractions, 3 to 5 times daily.

- It is ok to perform Kegels initially while urinating but after learning this should not be done all the time. It is best to practice Kegel exercises when not urinating.

Bladder Training

Bladder training involves a specific and graduated schedule for increasing the time between urinations:

- People start by planning short intervals between urinations, then gradually progressing with a goal of voiding every 3 to 4 hours.

- If the urge to urinate arises between scheduled voidings, people can do Kegel exercises until the urge subsides.

Vaginal Cones

This system uses a set of weights to improve pelvic floor muscle control:

- The typical set includes five cones of graduated weights ranging from 20 grams (less than 1 ounce) to 65 grams (slightly over 2 ounces).

- Starting with the lightest cone, the woman places the cone in her vagina while standing and attempts to prevent the cone from falling out. The muscles used to hold the cone are the same ones needed to improve continence.

As with standard Kegel exercises, frequent repetition is required, but most women will eventually be able to use the heavier weights and build up their muscle strength to prevent stress and urge incontinence.

Biofeedback Devices

Women who are unable to learn Kegel muscle contraction and release with verbal instructions may be helped with the use of biofeedback:

- Biofeedback uses a vaginal or rectal probe inserted by the patient that relays information to monitoring equipment.

- The patient isolates the pelvic floor and bladder muscles and performs Kegel exercises.

- The monitor emits auditory or visual signals that indicate how strongly the patient is contracting the proper pelvic floor muscles and how effectively the bladder muscles are being released.

- This can be done in the doctor's office. These are devices designed for home use.

As with any Kegel exercise regimen, biofeedback must be used for several months before it is effective. Biofeedback that teaches pelvic muscle control may also be helpful for children who have daytime wetting, frequent urinary tract infections, or both.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)

PTNS is a minimally invasive technique. The nerve that controls bladder function (i.e., the sacral nerve plexus) is stimulated indirectly by stimulation of the posterior tibial nerve, a nerve in the lower leg.

Treatment consists of:

- Insertion of a 34-gauge needle electrode about 2 inches above the medial (inside) malleolus and towards the back of the leg.

- Stimulation is administered for 30 minutes.

- Initial treatment course most often consists of 12 weekly sessions. In those who respond to this treatment some symptom improvement should be seen after 6 to 8 sessions.

- Ongoing treatment sessions may be needed.

PTNS appears to be an effective treatment for adult patients whose overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms persist despite standard medical therapy. This type of therapy may delay the need for additional or irreversible surgical procedures, such as urinary diversion.

The role of PTNS to improve symptoms in those with multiple sclerosis and other neurologic disorders is not as well proven.

Non-implanted electrical stimulation devices

Non-implanted devices can be used to electrically stimulate the pelvic floor muscles. These devices are inserted in the vagina or rectum and may help people with stress urinary incontinence who are unable to learn or to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises by themselves. The device may be used according to the same exercise schedule as a regular Kegel exercise regimen. Non-implanted electrical stimulation can be used by itself or together with Kegel exercises or vaginal cones.

Medications

Medications for treating urinary incontinence increase sphincter or pelvic muscle strength or relax the bladder, improving the ability to hold more urine. Medications are typically prescribed for urge incontinence (overactive bladder). Because these drugs can cause side effects, it's important to first try Kegel exercises, bladder training, and lifestyle modification methods.

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergics work by relaxing the bladder muscle and preventing bladder spasms that signal the urge to urinate. They also increase the amount of urine the bladder can hold.

These drugs can produce small but significant improvements in overactive bladder symptoms. Anticholinergics in pill form include:

- Oxybutynin (Ditropan, Ditropan XL, generic)

- Tolterodine (Detrol, Detrol LA, generic)

- Trospium (Sanctura, generic)

- Solifenacin (Vesicare, generic)

- Darifenacin (Enablex)

- Fesoterodine (Toviaz)

Oxybutynin is also available as a skin patch (Oxytrol). In 2013, the FDA approved an over-the-counter (OTC) version of the skin patch for women. Men will continue to need a prescription for the oxybutynin skin patch. Oxytrol is approved only for adults.

Dry mouth and constipation are the most common side effects of anticholinergic drugs. Other side effects include:

- Dry eyes

- Difficulty emptying bladder (urinary retention)

- Nausea and upset stomach

Alpha-Blockers

Alpha-blockers are drugs that relax smooth muscles and improve urine flow. They are useful for men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH, also called enlarged prostate), who also have urge incontinence. The older alpha-blockers terazosin (Hytrin) and doxazosin (Cardura) are now prescribed less often than the newer selective alpha-blockers tamsulosin (Flomax, generic), alfuzosin (Uroxatral), and silodosin (Rapaflo). Alpha-blockers are sometimes combined with anticholinergics to treat men with moderate-to-severe lower urinary tract symptoms, including overactive bladder.

Antidepressants

Both urge and stress incontinence are affected in part by chemical messengers in the brain (neurotransmitters) that affect pathways involved with urination. Antidepressants that target serotonin, norepinephrine, or noradrenaline neurotransmitters are sometimes used for urge incontinence, and may also be helpful for some people with stress incontinence.

- Imipramine (Tofranil) is the main tricyclic antidepressant prescribed for night-time frequency of urination (nocturia) or bedwetting. Tricyclic antidepressants act like anticholinergic drugs to relax the bladder muscle and ease spasms, as well as to tighten the sphincter. Like all tricyclic antidepressants, imipramine can cause side effects like sleepiness and dry mouth, as well as more serious side effects like abnormal heart rate or rhythm (arrhythmia). In some people, imipramine can cause urinary retention.

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is an antidepressant that targets the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine, which are thought to play key roles in the normal action of bladder muscles and nerves. Duloxetine is not approved in the United States for stress urinary incontinence, but it is sometimes prescribed off-label for this condition. Common side effects may include constipation or diarrhea, sleepiness, dry mouth, and headache.

Other Drugs

Mirabegron (Myrbetriq)

Mirabegron is a new, first-in-class drug that was approved in 2012 for the treatment of overactive bladder. Mirabegron is a beta-3 adrenergic agonist. It works in a different way than anticholinergics and other drugs used for urinary incontinence. Mirabegron is given to people with urgency urinary incontinence who do not tolerate anticholinergics or for whom these drugs did not provide relief of symptoms. This drug can increase blood pressure and may cause urinary retention in some people, especially those with bladder outlet obstruction.

Botox

In 2013, the FDA approved onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections to treat overactive bladder in people who have not been helped by anticholinergic drugs. The FDA previously approved Botox injections for urinary incontinence that results from neurological conditions such as spinal cord injury and multiple sclerosis. Botox is injected into the bladder using a cystoscopy procedure. Increased risk for urinary tract infections is the most common side effect.

Topical Estrogen

For women whose urinary incontinence is associated with menopause, topical estrogen may help improve urinary incontinence and overactive bladder symptoms. The estrogen is administered vaginally using a cream, tablet, or ring. Oral estrogen replacement should not be used to treat urinary incontinence because it can worsen the condition.

Alpha-Adrenergic Agonists

Alpha-adrenergic agonists, such as clonidine (Catapres), may be helpful for select people with mild stress incontinence, but these drugs can have significant side effects and are only rarely prescribed.

Surgery

There are different types of surgical procedures for incontinence. Most are designed to support the bladder neck and urethra to their anatomically correct positions in people with stress incontinence. Injections of bulking materials are another option for women and men.

The choice of surgical procedure depends on a number of factors, including the presence of bladder or uterine prolapse, the severity of incontinence, and the surgeon's experience in performing specific types of surgery.

In general, people should weigh all options carefully. They should discuss their situation with their doctor, and ask about their surgeon's experience. They should also be completely informed about the benefits and risks of the procedures and the materials used. People will need to have a complete diagnostic evaluation with urodynamic testing before any surgical procedure.

Sling Procedures

A sling procedure is usually the first-line surgical approach for stress incontinence in women. It may also be useful for managing female urge incontinence. Sling procedures are also used for men who experience incontinence after prostatectomy.

The purpose of a sling procedure is to create a sling or hammock around the neck of the bladder or below the middle of the urethra to help keep the urethra closed. There are different types of sling procedures. They include:

- Autologous fascial sling, which is the traditional type

- Midurethral, which includes retropubic transvaginal tape (TVT) and transobturator tape (TOT)

Autologous Fascial Sling Procedure

The autologous fascial, also called pubovaginal, sling is the traditional sling procedure. It uses a sling made from the person's own tissue. Suburethral means "beneath the urethra." The procedure generally works as follows:

- The surgeon makes an incision above the pubic bone and removes a layer of abdominal fascia (tissue that covers muscle fibers). This tissue strip is set aside and later serves as the sling.

- The surgeon makes an incision in the vaginal wall. The piece of tissue (fascia) is placed under the urethra and bladder neck, somewhat like a hammock, and secured to the abdominal wall.

- This sling then prevents excessive movement of the urethra during coughing, sneezing, and physical activity. The sling must be supportive without being too tense, which can cause urinary obstruction.

Complications can include infection, bleeding, pain with sex, and the formation of fistulas (holes that are usually infected).

Midurethral Sling Procedures

Midurethral sling procedures use slings made from synthetic mesh materials that are placed midway along the urethra. This newer type of sling procedure has largely replaced the conventional suburethral procedure because it can be performed on an outpatient basis using minimally invasive surgical techniques and no abdominal incisions. Midurethral sling procedures have high success rates and patient satisfaction.

There are two types of midurethral slings:

- In the retropubic procedure, the surgeon makes a small vaginal incision under the urethra and then two small incisions above the pubic bone.

- The transobturator procedure uses only a vaginal incision and two small inner thigh incisions.

- There is also a mini sling that only has one small vaginal incision.

Sling Procedures in Men

For some men who have prostatectomy-induced incontinence, sling procedures may be a good option. With mild to moderate amounts of incontinence, researchers have reported success rates similar to those of the artificial urinary sphincter, which is the standard surgical treatment for such patients. The sling procedure may be less effective for men who have undergone radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Minimally invasive procedures are also being tested.

Effectiveness and Complications

The sling procedure and the Burch colposuspension seem to have similar success rates for treating stress incontinence. Postoperative urinary problems, such as voiding problems, urinary tract infections, and urge incontinence may occur. The FDA has reported complications associated with some synthetic mesh slings.

Retropubic Colposuspension (Burch Colposuspension)

Retropubic colposuspension aims to correct the position of the bladder and urethra by sewing the bladder neck and urethra directly to the surrounding pelvic bone or nearby structures. Colposuspension is a common surgical treatment for stress incontinence.

Burch colposuspension is the standard approach. [Marshall-Marchetti Krantz (MMK) is an alternative approach.] It is often performed during abdominal surgeries such as hysterectomy or hernia operations. It is also performed along with sacrocolpopexy, a surgical procedure used to repair pelvic organ prolapse.

Pelvic organ prolapse occurs when the uterus or bladder slips from the pelvic cavity into the vagina. It is often due to pelvic muscle weakness that develops after childbirth. Prolapse can be associated with stress incontinence. However, prolapse surgery itself sometimes causes incontinence.

The Burch colposuspension procedure may be performed using open surgery or laparoscopy using spinal or general anesthesia. The surgeon makes an abdominal incision and secures the urethra and bladder neck with lateral (sideways) sutures that pass through thick bands of muscle tissue running along the pubic bones.

Effectiveness and Complications

Patients may stay in the hospital for a few days and usually need to use a urinary catheter for about 10 days after surgery. Because colposuspension surgery involves an abdominal incision, it can take up to 6 weeks for full recovery. (Laparoscopic procedures have a faster recovery time than open surgery.)

Complications can include problems with wound healing and postoperative voiding function. Convalescence time is longer with retropubic colposuspension than with sling procedures.

Artificial Sphincter

In cases of sphincter incompetence or complete lack of sphincter function, an artificial internal sphincter may be implanted. This procedure is generally used for men, such as those who have experienced incontinence following radical prostatectomy.

This device uses a balloon reservoir and a cuff around the urethra that is controlled with a pump. The patient opens the cuff manually by activating the pump. The urethra opens and the bladder empties. The cuff closes automatically several minutes later. The two major drawbacks of the internal sphincter implant are malfunction of the implant and risk of infection.

Bulking Material Injections

Injections of materials, such as microscopic carbon particles, that provide bulk to help support the urethra may help the following people:

- Women with severe stress incontinence who cannot or do not wish to have surgery that involves anesthesia.

- Men who have slight incontinence caused by prostate surgery procedures such as transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or radical prostatectomy (removal of the prostate gland in prostate cancer).

The Procedure

- The basic procedure involves injecting bulking material into the tissue surrounding the urethra.

- The material used is synthetic, such as carbon-coated beads or silicone. Collagen used to be the most common material but is no longer used and no longer commercially available.

- The doctor passes the injection needle through a cystoscope, a tube that has been inserted into the urethra. The bulking material can also be injected into the skin next to the sphincter.

- The injected material tightens the seal of the sphincter by adding bulk to the surrounding tissue.

- The procedure takes about 20 to 40 minutes, and most people can go home immediately afterward.

- Two or three additional injections may be needed to achieve satisfactory results.

Postoperative Care

People may experience immediate improvement followed by a temporary relapse after a week or so. They must be taught to use a catheter tube for withdrawing urine for a few days following the procedure. In general, it takes about a month for the full benefits to become apparent.

Complications

Bulking material injections pose a risk for infection and urinary retention, but these complications are usually temporary. This procedure may not be appropriate for people with certain heart conditions.

Duration of Effectiveness

Injections with collagen generally needed to be repeated every 6 to 18 months, as collagen is absorbed over time. Injections with synthetic materials need to be repeated less often.

Sacral Neurostimulation

The sacral nerves, located near the sacrum (tailbone), appear to play an important role in regulating bladder control. A sacral nerve stimulation system (InterStim) may help some people with urge incontinence. The system uses an implanted device to send electrical pulses to the sacral nerves to help retrain them. InterStim is reserved for the treatment of urinary retention and the symptoms of overactive bladder in people who have failed or cannot tolerate less invasive treatments.

Complications include infection, lower back pain, and pain at the implant site. The system does not cause nerve damage and can be removed at any time.

People have reported improvement in the frequency and volume of urination, as well as in the intensity of urgency, urge incontinence episodes, and their quality of life.

Lifestyle Changes

Hygiene Tips

Keeping Skin Clean

Proper hygiene is essential for patients with incontinence.

To avoid skin irritation and infection associated with incontinence, keep the area around the urethra clean. The following tips may be helpful:

- After a urinary accident, clean any affected areas right away.

- When bathing, use warm water but don't scrub forcefully -- hot water and scrubbing can injure the skin.

- Cleansers are available that are specially created for incontinence and allow frequent cleansing without over-drying or causing irritation to the skin. Most do not have to be rinsed off; the area is simply wiped with a cloth.

- After bathing, apply a moisturizer plus a barrier cream. Barrier creams include petroleum jelly, zinc oxide, cocoa butter, kaolin, lanolin, or paraffin. These products are water repellent and protect the skin from urine.

- Antifungal creams that contain miconazole nitrate are used for yeast infections.

Preventing or Reducing Odor

Certain methods may help reduce odor from accidents. They include:

- Deodorizing tablets can be taken by mouth.

- Drinking more water will reduce odors, and may actually help reduce leakage, too. Drinking non-citrus fruit juices such as apple, pear, or cherry juices can help minimize odors.

- To remove odors from mattresses, use a solution of equal parts vinegar and water. Once the mattress has dried, apply baking soda on the stain, rub it in, and then vacuum it off.

Dietary Considerations

Diet and Weight Control

In women, pelvic floor muscle tone weakens with significant weight gain. Weight loss can help reduce the frequency of urinary incontinence episodes in overweight women. Women should eat healthy foods in moderation and exercise regularly. Constipation can worsen urinary incontinence, so diets should be high in fiber, fruits, and vegetables.

Fluid Intake

Drinking less water can prevent accidents. But it is important not to dehydrate yourself.

People with incontinence should stop drinking beverages 2 to 4 hours before going to bed, or before traveling when a bathroom will not be available, particularly those who experience leakage or accidents during the night.

Fluid and Food Restrictions

A number of foods and beverages may increase incontinence. People who drink caffeinated or alcoholic beverages should try eliminating them to see if incontinence improves. Spicy and acidic foods such as chocolate or tomatoes may also need to be avoided.

Considerations for Exercising

Sometimes otherwise healthy adults stop exercising because of leakage. There are a number of methods for preventing or stopping leakage during exercise. The following are some tips:

- Limit fluid intake before exercising (but be sure not to become dehydrated.)

- Urinate frequently, including right before exercise.

- Women can try wearing pads, urethral inserts, or other temporary incontinence products that can be inserted into the vagina, like a tampon.

Urinary Incontinence Products

Many products are available to help patients avoid embarrassment and prevent leakage.

Absorbent Pads and Protective Undergarments

A variety of absorbent pads and undergarments are effective in catching spills and leaks. Newer types of pads are thin enough to be worn undetected, and a spare can be hidden in a purse or pocket. Many undergarments developed for incontinence are almost indistinguishable from regular briefs and underpants.

For men, drip collectors are available that can be worn under briefs and are not noticeable under normal clothing. Lined with absorbent material, the pouch-like collector surrounds the penis or scrotum and is fastened with a belt or pins.

All absorbent undergarments should be changed when wet to limit problems of chafing or infection.

External Devices

Self-Adhesive Foam Pads

Foam pads with an adhesive coating are available for women with stress incontinence. They work as follows:

- The pad is placed over the opening of the urethra where it creates a seal, preventing leakage.

- It is removed before urinating and replaced with a new one afterward.

- The pad can be worn up to 5 hours a day and through the night.

- It can be used during physical activity, although it may change position during vigorous exercise.

- It should not be worn during sexual intercourse.

Adhesive pads should not be used by women with the following conditions:

- Urinary tract or vaginal infections.

- Urge or other forms of non-stress incontinence.

- A history of surgery for incontinence.

Urethral Caps

Small silicone caps that use suction to adhere to the urethral opening are also an option for women. These caps may be uncomfortable for some women, and side effects can include irritation and urinary tract infections.

Penile Clamps

The penile clamp is a hinged, V-shaped external device that has two foam rubber pads that fit over the penis. When it is locked in place, it helps prevent dribbling. To urinate, the man releases the clamp.

Internal Devices

Vaginal Pessaries

Vaginal pessaries are devices inserted into the vagina that support the inside of the vaginal walls. Pessaries are usually made of silicone and come in various forms, including donut or cube shapes. They must be fitted by a health professional and are effective for vaginal prolapse or other vaginal structural problems. Serious complications are rare, but can occur if the pessary is not replaced periodically.

Urethral Inserts

Urethral inserts are tampon-like silicone tubes or sleeves that fit into the urethral opening. When the tube is inserted into the urethra, the sleeve conforms to its shape and creates a seal at the bladder neck, preventing leakage. The insert is intended for one-time use and is replaced after voiding.

Catheters and Collection Devices

A catheter is a slim, flexible tube inserted into the urethra. Catheters are mainly used for cases of severe overflow incontinence, which may occur in patients who have neurogenic bladder due to neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson disease, or diabetes. Catheters are also used after some surgical procedures.

A catheter (hollow tube) may be inserted into the urinary bladder when there is a urinary obstruction, following surgical procedures to the urethra, in unconscious patients (due to surgical anesthesia or coma), or for any other problem in which the bladder needs to be kept empty (decompressed) and urinary flow assured.

Temporary Catheterization

For people who are still active, catheterization is often problematic. When appropriate, temporary (also called intermittent) catheterization is usually best. People insert the catheter tube into their urethras, generally every 3 to 4 hours. This type of catheterization carries few risks and empties the bladder completely. Some people report that they can maintain an active life with no significantly increased risk for infection with some simple precautions:

- Sterilize catheters at home.

- Use a ziplock plastic bag for carrying them when leaving home.

- Use another plastic bag for antiseptic cleansing solution.

- When using public bathrooms, wash before and after catheterization. Touch as few places in the bathroom as possible.

Permanent Catheterization

People who are mentally or physically incapable of self-catheterization may need permanent catheterization.

- The permanent catheter is inserted into the opening of the bladder by a doctor or nurse and a balloon is inflated to hold the tube in place. (A suprapubic tube may be recommended for long-term use. It is an indwelling catheter that is surgically placed directly into the bladder through the abdomen. The catheter is inserted above the pubic bone.)

- Urine drains to an external collection device, which is generally strapped to the leg and must be emptied periodically.

Nonsurgical catheterization procedures are generally not painful, but there is a substantial increased risk for urinary tract infections. Many doctors feel that the catheter is overused, especially in the elderly.

External Collection Devices

External catheter and collection devices include:

- Condom catheters. Condom catheters are much more comfortable than standard catheters for many male patients, although there is more spillage. The disposable condom is worn all day and at night it is removed or replaced with a new one.

- Collection devices attached to the leg. For chronic or severe incontinence, collection devices drain urine into a bag that is attached to the lower leg and emptied periodically. These are generally more successful for men than women. Urine can be funneled into the tube by a pouch surrounding the penis. The positioning of the collecting device is more difficult for women. For both men and women, irritation of the area around the urethral opening is a problem, since urine is in contact with the area for long periods.

Resources

- National Association for Continence -- www.nafc.org

- The Simon Foundation for Continence -- simonfoundation.org

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease -- www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease

- The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists -- www.acog.org

- Urology Care Foundation -- www.urologyhealth.org

References

Al-Mousa RT, Hashim H. Evaluation and management of men with urinary incontinence. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 113.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 603. Evaluation of uncomplicated stress urinary incontinence in women before surgical treatment. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1403-1407. PMID: 24848922 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24848922/.

Aoki Y, Brown HW, Brubaker L, Cornu JN, Daly JO, Cartwright R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17042. PMID: 28681849 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28681849/.

Chermansky CJ, Chancellor MB. Use of botulinum toxin in urologic diseases. Urology. 2016;91:21-32. PMID: 26777748 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26777748/.

Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005654. PMID: 30288727 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30288727/.

Foster HE, Barry MJ, Dahm P, et al. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2018;200(3):612-619. PMID: 29775639 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29775639/.

Hu JS, Pierre EF. Urinary incontinence in women: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(6):339-348. PMID: 31524367 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31524367/.

Kobashi KC. Evaluation and management of women with urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:chap 71.

Kobashi KC, Albo ME, Dmochowski RR, et al. Surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: AUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol. 2017;198(4):875-883. PMID: 28625508 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28625508/.

Lemack GE, Carmel M. Urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse; epidemiology and pathophysiology. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 115.

Lightner DJ, Gomelsky A, Souter L, Vasavada SP. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment 2019. J Urol. 2019;202(3):558-563. PMID: 31039103 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31039103/.

Lipp A, Shaw C, Glavind K. Mechanical devices for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD001756. PMID: 25517397 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25517397/.

Lucioni A, Kobashi KC. Evaluation and management of women with urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 112.

Lukacz ES, Santiago-Lastra Y, Albo ME, Brubaker L. Urinary incontinence in women: a review. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1592-1604. PMID: 29067433 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29067433/.

Newman DK, Burgio KL. Conservative management of urinary incontinence: behavioral and pelvic floor therapy and urethral and pelvic devices. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, eds. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021: chap. 121.

Stewart F, Berghmans B, Bø K, Glazener CM. Electrical stimulation with non-implanted devices for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD012390. PMID: 29271482 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29271482/.

Suarez OA, McCammon KA. The artificial urinary sphincter in the management of incontinence. Urology. 2016;92:14-19. PMID: 26845050 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26845050/.

Thomas LH, Coupe J, Cross LD, Tan AL, Watkins CL. Interventions for treating urinary incontinence after stroke in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD004462. PMID: 30706461 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30706461/.

|

Review Date:

5/29/2021 Reviewed By: Kelly L. Stratton, MD, FACS, Associate Professor, Department of Urology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.