Eating disorders - InDepth

Highlights

Eating Disorders Overview

- Eating disorders most often occur in young women, but can occur in any gender and at any age.

- Bulimia nervosa involves a pattern of bingeing and purging.

- Anorexia nervosa involves a pattern of self-starvation and other behaviors to restrict weight gain, but can also include binge eating and purging.

- Binge eating disorder is characterized by episodes of uncontrolled eating, without purging behavior.

Complications of Bulimia Nervosa

People with bulimia nervosa may make themselves vomit or use laxatives or diuretics to rid themselves of consumed calories. Many medical problems are directly associated with purging behavior, including:

- Tooth erosion, cavities, and gum problems

- Water retention, swelling, and abdominal bloating

- Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances

- Stomach problems and constipation

- Swallowing problems and esophagus damage

Complications of Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa can increase the risk for serious health problems, such as:

- Hormonal changes including reproductive, thyroid, stress, and growth hormones

- Heart problems such as abnormal heart rhythm

- Fertility problems

- Bone density loss

- Anemia

- Neurological problems

Complications of Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating disorder can lead to obesity. Obesity is associated with increased risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease and osteoarthritis.

Treatment of Bulimia Nervosa

- Bulimia nervosa is treated with a combination of nutritional counseling, psychotherapy, and medication.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is given along with nutritional counseling, is the preferred psychotherapeutic approach.

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine (Prozac), are the first choice for drug therapy.

Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa

- Restoring a healthy weight and providing nutritional therapy are the first goals of treatment for anorexia nervosa. People who are severely underweight may need to be hospitalized while weight is restored.

- Psychotherapy combined with nutritional rehabilitation counseling is the main treatment for anorexia nervosa. There are various types of psychotherapeutic approaches, such as family-based treatment (the 'Maudsley method') and supportive psychotherapy.

- Unlike bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa does not respond well to drug treatment, however SSRIs are sometimes used as an adjunct to psychotherapy.

Introduction

Eating disorders are psychological problems marked by disturbances in body image, weight control, and dieting patterns. The main types of eating disorders are:

- Anorexia nervosa

- Bulimia nervosa

- Binge eating disorder

Anorexia Nervosa

There are three main features of anorexia nervosa:

- Persistent restriction of caloric intake, leading to below-normal body weight.

- Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, or engaging in behavior to prevent weight gain even when severely underweight.

- Distorted image of body weight and shape and lack of recognition of the serious health consequences of low weight.

Anorexia nervosa has two subtypes, based on a person's behavior during the past 3 months:

- Restrictive type. Reducing weight mainly through dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise.

- Binge eating/purging type. Maintaining low weight through episodes of binge eating and purging (self-induced vomiting or the use of laxative, diuretics, or enemas). Some people do not binge eat, but purge after eating even small amounts of food.

- There is frequent crossover between these subtypes during the course of the illness.

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by cycles of bingeing and purging:

- Binge eating involves consuming larger than normal amounts of food within a 2-hour period. It is accompanied by a sense of lack of control. The person feels incapable of stopping eating or controlling what or how much to eat.

- In response to the binges, people compensate through purging in order to prevent weight gain. Purging methods include vomiting; using enemas, laxatives, diuretics (water pills), or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise.

- On average, binge eating and purging behaviors occur at least once a week for 3 months.

- The person's self-esteem is based on constant critical self-evaluation of body shape and weight.

- People with bulimia nervosa are usually normal weight or overweight.

Binge Eating Disorder

Bingeing without purging is characterized by uncontrolled overeating (binge eating) and the absence of purging behaviors, such as vomiting or laxative abuse (used to eliminate calories). Binge eating usually leads to becoming overweight.

Binge eating is characterized by:

- Recurrent episodes of consuming larger than normal amounts of food within a 2-hour period, accompanied by a sense of lack of control.

- At least three of these additional behaviors: Eating more rapidly than normal; eating until feeling uncomfortably full; eating large amounts of food even when not hungry; eating alone because of embarrassment by how much one is consuming; feeling extremely guilty, depressed, or disgusted with oneself after a binge eating episode.

- Eating in secrecy. People who binge eat are usually very ashamed of their eating behavior and try to conceal it.

Causes

There is no single cause for eating disorders. Although concerns about weight and body shape play a role in all eating disorders, the actual cause of these disorders appears to involve many factors, including those that are genetic and neurobiological, cultural and social, and behavioral and psychological.

Genetic Factors

Anorexia is much more common in people who have relatives with the disorder. Studies of twins show they have a tendency to share specific eating and weight disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and obesity). Researchers have identified specific chromosomes that may be associated with bulimia and anorexia.

Biological Factors

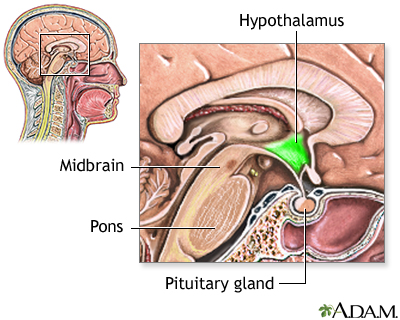

The body's hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) may be important in eating disorders. This complex system originates in the following regions in the brain:

- Hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is a small structure that plays a role in controlling behaviors such as eating, sexual behavior, and sleeping. It regulates body temperature, hunger and thirst, and secretion of hormones.

- Pituitary gland. The pituitary gland is involved in controlling thyroid functions, the adrenal glands, growth, and sexual maturation.

- Amygdala. This small almond-shaped structure lies deep in the brain and is associated with regulation and control of major emotional activities including anxiety, depression, aggression, and affection.

The HPA system is regulated by certain regions of the brain and by certain neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) that regulate stress, mood, and appetite. Three neurotransmitters, serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, may play particularly important roles in eating disorders.

Serotonin is involved with well-being, anxiety, and appetite (among other traits). Norepinephrine is a stress hormone. Dopamine is involved in reward-seeking behavior. Imbalances with serotonin and dopamine may explain in part why people with anorexia do not experience a sense of pleasure from food and other typical comforts.

Hormones that regulate appetite and energy storage may also play a role in eating disorders, including ghrelin, leptin, and others.

Psychological Factors

Many people with eating disorders also experience depression, anxiety disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). It is not clear if these disorders, particularly OCD, cause the eating disorders, increase susceptibility to them, or share common biologic causes.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

OCD is a mental health disorder that may occur in up to two-thirds of people with anorexia and up to a third of people with bulimia. Some experts believe that eating disorders are variants of OCD.

Obsessions are recurrent or persistent mental images, thoughts, or ideas, which may result in compulsive behaviors, which are repetitive, rigid, and self-prescribed routines. People with anorexia and OCD may become obsessed with exercise, dieting, and food. They often develop compulsive rituals (weighing each bit of food, cutting it into tiny pieces, or putting it into small containers). People with binge eating disorder may become obsessed with food and develop compulsive eating behaviors.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

BDD is related to OCD. It is a compulsive disorder that involves a distorted obsession with finding fault with one's body. BDD is often associated with anorexia or bulimia, but it can also occur without any eating disorder.

Muscle dysmorphia is a form of body dysmorphic disorder in which the obsession involves musculature and muscle mass. It tends to occur in men who perceive themselves as being underdeveloped or "puny," which results in excessive body building, preoccupation with diet, use of anabolic steroids, and eating disorders.

Cultural Factors

Cultural values that emphasize only certain types of body shapes as desirable or normal contribute to eating disorders. The media often promotes contradictory and confusing messages. It encourages unrealistic expectations for body image and a distorted cultural drive for thinness. At the same time, cheap and high-caloric foods are aggressively marketed.

Risk Factors

Age

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa occur most often in adolescents and young adults. These disorders rarely begin before puberty or after age 40 years. Binge eating disorder typically begins during adolescence or young adulthood, but it can also first develop in older adults.

Gender

Eating disorders occur predominantly among girls and women. About 90% of people with anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa, are female.

Race and Ethnicity

Most studies of individuals with eating disorders have focused on Caucasian middle-class females. However, eating disorders can affect people of all races and socioeconomic levels.

Personal History

Some people with eating disorders are survivors of emotional or physical trauma. These stressful life experiences may have included physical or sexual abuse, painful loss of loved ones, or having lived through war or natural disasters. Bullying may contribute to eating disorders, especially if the ridicule and humiliation are directed at the victim's weight and body shape.

Research indicates that exposure to trauma, and development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), may increase the risk for eating disorders.

Personality Traits

People with eating disorders tend to share certain personality and behavioral traits including low self-esteem and obsessions with weight and body shape and size. There are also differences depending on the type of eating disorder:

- Anorexia nervosa is associated with perfectionist personalities. Perfectionists are often very inflexible and rigid in their thinking, and want to control their environment. They strive to be perfect in all of their accomplishments, and regard falling short in their goals as a sign of personal failure. As manifested in anorexia, perfectionists starve themselves to achieve an unattainable goal of physical perfection. They consider weight loss, even if it is dangerous, as an achievement of self-control.

- Binge eating and purging are associated with impulsive personalities. Impulsivity is linked to novelty-seeking behavior, people who seek new sensations and stimulations. Impulsive individuals often engage in risky behavior and have an increased risk for abusing alcohol and other drugs. Binge eating is included in the diagnosis for borderline personality disorder, a mental health condition associated with self-destructive and impulsive behaviors.

Dieting

A history of dieting or food restriction is associated with increased risk for eating disorders. Although there is no evidence that families or parents cause eating disorders, research suggests that parental conversations that focus on weight and size may increase the risk for eating disorders. In contrast, engaging adolescents in conversations about healthy eating may help prevent eating disorders.

Exercise and Sports

Excessive exercise is associated with many cases of anorexia (and, to a lesser degree, bulimia). In young female athletes, exercise and low body weight postpone puberty, allowing girls to retain a muscular boyish shape without the normal accumulation of fatty tissues in breasts and hips that may blunt their competitive edge. Coaches and teachers may compound the problem by overemphasizing calorie counting and loss of body fat.

The "female athlete triad" syndrome is a combination of eating disorders, amenorrhea (absent or irregular menstruation), and osteoporosis (loss of bone mineral density). However, eating disorders also affect male athletes. Male wrestlers are particularly notorious for using a method called weight-cutting for rapid weight loss. This process involves food restriction and fluid depletion by using steam rooms, saunas, laxatives, and diuretics.

Complications

Eating disorders are very serious illnesses that have wide range of effects on the body and mind. They are frequently associated with a number of other medical problems, ranging from frequent infections and general poor health to life-threatening conditions. Starvation, binge eating, and purging can cause damage to many of the body's organs including the kidneys, lungs, and liver. Severe anorexia nervosa can cause multi-organ failure.

Gastrointestinal Complications

Purging can cause extensive damage throughout the digestive tract. Complications include:

- Frequent use of laxatives can cause dehydration, bloating, and electrolyte imbalances, which can lead to many other medical complications. Laxative abuse can cause colon damage that may result in chronic constipation.

- Acid and bile from frequent forced vomiting can cause inflammation and damage to the lining of the esophagus, stomach, and entire gastrointestinal tract. Resulting complications include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gastritis, and esophagitis. In severe cases, the esophagus can rupture.

Heart Complications

Heart disorders are the most common medical causes of death in people with severe anorexia nervosa. The effects of anorexia on the heart may include:

- Dangerous heart rhythms, including slow rhythms known as bradycardia. Bradycardia is a slowness of the heartbeat, usually at a rate under 60 beats per minute (normal resting rate is 60 to 100 beats per minute). These rhythm abnormalities are triggered by dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

Hormonal Complications

Starvation can cause serious hormonal changes, which may have severe health consequences. Hormones affected include:

- Reproductive hormones, including estrogen and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

- Thyroid hormones

- Stress hormones

- Growth hormones

In women, these hormonal abnormalities can cause irregular or absent menstruation (amenorrhea). This menstrual problem can occur early on in anorexia, even before severe weight loss. Over time hormonal imbalances can lead to infertility and pregnancy complications, thinning bones (osteoporosis), and other problems.

In children and adolescents with eating disorders, hormonal complications can interfere with normal bone development and growth.

Bone Complications

Nearly all people with anorexia experience osteopenia (loss of bone calcium), and many have osteoporosis (more advanced loss of bone density). Most of the children and adolescent girls with anorexia have weak bones during their critical growth period. Boys with anorexia also have slow growth. The less a person weighs, the more severe the bone density loss. People who binge-purge face an even higher risk for bone density loss.

Bone density loss in women is mainly due to low estrogen levels that occur with anorexia. Other biologic factors in anorexia also may contribute to bone density loss, including high levels of stress hormones (which impair bone growth) and low levels of calcium, certain growth factors, and DHEA (a weak male hormone). Unfortunately, gaining weight does not completely restore bone density. However, a regular menstruation can prevent permanent loss of bone density. The longer the eating disorder persists the more likely the bone density loss will be permanent.

Testosterone levels decline in boys as they lose weight, which also can affect their bone density. In boys with anorexia, weight restoration produces some catch-up growth, but it may not produce full growth.

Blood Complications

Anemia (reduced number of red blood cells) is a common result of malnutrition and starvation. A particularly serious blood problem is caused by severely low levels of vitamin B12. If anorexia becomes extreme, the bone marrow dramatically reduces its production of blood cells, a life-threatening condition called pancytopenia.

Teeth and Skin Complications

Tooth erosion, cavities, mouth sores, and gum problems are common in people who purge. The stomach acid caused by forced vomiting erodes tooth enamel and dries out the saliva glands.

Dehydration affects people with bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. It can cause dry, flaky skin and brittle hair. People may lose hair on the scalp, but grow a layer of downy hair elsewhere, which is the body's attempt to try to stay warm.

Neurological Complications

Neurological conditions associated with severe anorexia nervosa include:

- Seizures

- Disordered thinking

- Numbness or odd nerve sensations in the hands or feet (peripheral neuropathy)

Imaging scans indicate that parts of the brain physically shrink (atrophy) during anorexic states. Weight gain helps many people recover brain function, but some damage may be permanent.

Emotional Complications

Anxiety disorders and depression are common in people with eating disorders. They are also at higher risk for substance abuse including smoking (to help prevent weight gain), alcohol, and drug abuse. In addition to illegal drugs, people with eating disorders often abuse over-the-counter laxatives, diuretics, appetite suppressants, and drugs that induce vomiting (such as ipecac). Some people with anorexia nervosa are at risk for suicidal behavior.

Diabetes Complications

Eating disorders are particularly serious for people with diabetes (type 1 or type 2).

Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) is a danger for anyone with anorexia, but it poses a particular risk for people with diabetes, especially those who take supplemental insulin. If people do not take their insulin, dangerous high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) can occur. Unfortunately, people with eating disorders may skip or reduce their daily insulin in order to decrease their body's utilization of calories.

Extremely high blood sugar levels can cause life-threatening complications. They include diabetic ketoacidosis, a condition in which acidic chemicals (ketones) accumulate in the body. This condition can lead to coma and death.

Symptoms

Symptoms Specific to Anorexia Nervosa

The main symptom of anorexia nervosa is major weight loss from excessive and continuous dieting.

Behavioral symptoms and warning signs of anorexia may include:

- Obsessive dieting

- Compulsive exercising

- Frequent weighing, measuring of body parts, self-critiquing in mirror

- Fixation on food and calories

- Distorted perception of body image

- Concerns about weight gain in spite of continued weight loss

- Secrecy and denial about food and weight issues

- Ritualistic eating, including cutting food into small pieces

- Pushing food around plate to give appearance of eating

- Episodes of binge eating

Other symptoms of anorexia may include:

- Infrequent or absent menstrual periods

- Low blood pressure

- Swollen hands or feet

- Yellowish skin, especially on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (from eating too many vitamin A-rich vegetables such as carrots)

- Hypersensitivity to cold (some women wear several layers of clothing to both keep warm and hide their thinness)

- Thin, brittle, patchy scalp hair

- Dry body skin, which may be covered with fine hair

- Stomach problems, including constipation and bloating after eating

- Confused or slowed thinking

- Depression

Symptoms Specific to Bulimia Nervosa

Symptoms and signs of binge eating and purging behaviors may include:

- Regularly going to the bathroom right after meals.

- Suddenly eating large amounts of food or buying large quantities that disappear right away.

- Ritualistic planning and preparation of binge eating meals and opportunities.

- Not wanting to eat in public (because of embarrassment of how much one eats).

- Broken blood vessels in the eyes (from the strain of vomiting).

- Pouch-like appearance to the corners of the mouth due to swollen salivary glands.

- Dry mouth and skin.

- Tooth cavities, diseased gums, and enamel erosion from excessive gastric acid produced by vomiting.

- Small cuts and calluses across the tops of finger joints due to self-induced vomiting.

- Stomach problems including bloating and constipation from laxative abuse.

- Evidence of discarded packaging for laxatives, diet pills, emetics (drugs that induce vomiting), or diuretics (drugs that reduce fluid by increasing urination).

- Feeling out of control.

- Feeling ashamed and guilty of binge eating and purging behavior.

Diagnosis

The first step toward a diagnosis is to admit the existence of an eating disorder. Oftentimes, people with eating disorders deny they have a problem.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, people with eating disorders (especially anorexia nervosa) frequently lack insight into their condition. Therefore, health care providers may turn to family members for information regarding weight loss and additional symptoms. Because people who purge tend to have complications with their teeth and gums, dentists can play a role in identifying eating disorders.

Measuring Body Mass Index

A provider will evaluate a person's body mass index (BMI). The BMI is a screening tool for the body weight category. You can calculate your BMI by dividing your weight in kilograms by your squared height in meters. (BMI calculators are available online.)

BMI ranges are:

- Below 18.5: Underweight

- 18.5 to 24.9: Normal weight

- 25.0 to 29.9: Overweight

- 30 or above: Obese

For example, a woman who is 5'5" (1.65 m) and weighs 125 pounds (lbs) or 59 kilograms (kg) has a healthy BMI of 21. A woman at the same height who weighs 90 lbs (41 kg) would have a dangerously low BMI of 15.

Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders

A provider will carefully evaluate a person's medical history, symptoms, and mental health. The provider will ask questions about eating behaviors and any family history of eating disorders or weight issues.

Eating disorders are diagnosed based on criteria from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). [See Introduction section of this report for a complete list of diagnostic criteria.] The criteria outline specific behaviors and symptoms that define anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and other eating disorders.

Diagnosing Complications of Eating Disorders

The provider will check for any serious complications of eating disorders. Tests may include:

- Complete blood count

- Blood chemistry screen to measure electrolytes, cholesterol, and other substances in blood

- Tests for liver and kidney function

- Endocrine tests for thyroid, estrogen (female), and testosterone (male) levels

- Electrocardiogram to evaluate heart rhythm

- Bone density test

- Dental exam

Screening Tests

The Eating Disorders Examination (EDE), which is used by a clinician to interview the person, and the self-reported Eating Disorders Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) are considered the best tests for diagnosing eating disorders and assessing specific features (such as vomiting or laxative use). Each test has different strengths and weaknesses. The EDE is time consuming, but allows the provider to ask extra questions. The EDE-Q overcomes the time constraint but only covers the history for the past 28 days.

Another test is called the SCOFF questionnaire. Answering yes to two of these questions is a strong indicator of an eating disorder:

- Do you make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than One stone's worth of weight (14 lbs or 6 kg) in a 3-month period?

- Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that Food dominates your life?

Eating disorders are often accompanied by body image disturbance or body dissatisfaction. Several measures and tests developed to assess body image disturbance are available, and they may help with prognosis and treatment management.

Treatment

Treatment goals for eating disorders include:

- Restore normal weight for anorexia nervosa.

- Reduce, and hopefully stop, binge eating and purging for bulimia nervosa.

- Treat physical complications and any associated psychiatric disorders.

- Teach proper nutritional habits and how to develop healthy eating patterns and meal plans.

- Change dysfunctional thoughts about the eating disorder.

- Improve self-control, self-esteem, and behavior.

- Provide family counseling.

- Prevent relapse.

A multidisciplinary team approach with consistent support and counseling is essential for long-term recovery. Depending on the severity and type of eating disorder, team members may include:

- Psychiatrists to address mental health aspects and coordinate care.

- Doctors and dentists to treat medical and dental complications.

- Dietitians and to provide nutritional counseling.

- Psychotherapists and social workers to provide individual or family counseling.

All health care providers should be experienced in treating eating disorders.

General Treatment Approaches

Eating disorders are nearly always treated with some form of psychological treatment. Depending on the disorder and the individual, certain psychotherapeutic approaches may work better than others.

Nutritional rehabilitation counseling is essential for recovery. It can help people develop structured meal plans and healthy eating and weight management. In anorexia nervosa, family-based therapies that involve a parent's assistance in feeding can be very helpful.

Medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants may be added to psychotherapy for bulimia, but there is limited evidence that these or other drugs have any significant effect on anorexia nervosa.

Although anorexia nervosa generally presents more treatment challenges than bulimia nervosa, long-term studies show recovery in many people treated for anorexia. Studies indicate that up to 45% of people with bulimia nervosa, and almost half of people with anorexia nervosa, are free from eating disorders following treatment.

Choosing a Treatment Setting

The person's overall physical condition, psychology, behavior, social circumstances, and health insurance determine the type of treatment facility, such as inpatient hospitalization, residential hospitalization, partial hospitalization, or outpatient care. People and their families should discuss with their doctors the various options available and the structured and intensity of the treatment.

Hospitalization may be required when:

- Weight loss continues even with outpatient treatment

- Weight is 15% below normal

- Depression is severe or the person is suicidal

- There are symptoms of medical complications (disturbed heart rate, low potassium levels, and low core body temperature)

When severe metabolic or medical problems occur, people with eating disorders may need to be hospitalized either voluntarily or involuntarily. A variety of partial hospitalization or day care programs are also available.

Treatment for Anorexia Nervosa

Nutrition rehabilitation and psychotherapy are the cornerstones of anorexia nervosa treatment.

Nutritional Interventions

The first step for treatment is to help the person reach a healthy weight. Nutritional intervention is essential to achieve weight gain, normalize eating patterns and perceptions of hunger and fullness, and improve overall health. A registered dietician can help design an eating plan and teach skills for choosing nutritional meals.

Goals for weight gain are 2 to 3 lbs (0.9 to 1.4 kg) a week for hospitalized people and 0.5 to 1 lbs (0.2 to 0.4 kg) a week for outpatients. People typically begin with a calorie count as low as 1,000 to 1,600 calories a day, which is then gradually increased to 2,000 to 3,500 calories a day.

Side effects may accompany the early stages of weight gain. People may initially experience psychological symptoms such as intensified anxiety and depression, as well as physical symptoms such as fluid retention and constipation. These symptoms decrease as the weight is maintained.

Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition

People who are hospitalized for severe malnutrition may require tube feeding (enteral) or intravenous feeding (parenteral) nutrition. Enteral nutrition uses feeding tubes that pass through the nose to the stomach or through the abdominal skin to the stomach. Parenteral nutrition involves inserting a needle into the vein and infusing fluids containing nutrients directly into the bloodstream.

Intravenous feedings must be administered slowly and carefully to avoid refeeding syndrome. This condition causes dangerous hormonal and metabolic fluctuations that affect fluid and electrolyte balances. If not controlled, it can result in heart failure. The person's heart rhythms, and phosphate and magnesium levels, must be carefully monitored.

The Maudsley Approach

For adolescent and other younger people in the early stages of anorexia nervosa, the Maudsley approach to refeeding may be effective. The Maudsley approach is a type of family therapy that enlists the family as a central player in the person's nutritional recovery. Parents take charge of planning and supervising all of their child's meals and snacks. As recovery progresses, the child gradually takes on more personal responsibility for determining when and how much to eat. Weekly family meetings and family-based counseling are also part of this therapeutic approach.

Psychotherapy and Medications for Anorexia Nervosa

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is the main therapeutic approach for anorexia nervosa. Psychotherapy may be given in an individual, group, or family setting. Family therapy is an important component of anorexia treatment for children and adolescents.

Individuals usually begin with a form of psychodynamic psychotherapy that provides an empathetic setting, addresses unresolved emotional issues, and rewards positive efforts towards weight gain. Some people also benefit from incorporating approaches such as art therapy. After weight is restored, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques may be helpful.

Antidepressants

Studies have not reported benefits for treating anorexia nervosa with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the antidepressants that are often useful for people with bulimia. A few studies suggest that these drugs could be useful for people with anorexia nervosa who also have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Nutritional Supplements

People with anorexia nervosa often have deficiencies in important vitamins and minerals such as vitamins B12, C, and D and minerals calcium, iron, zinc, and magnesium. Vitamin and mineral supplements may be recommended.

Exercise in Recovery

The role of exercise in recovery is complex for those with anorexia, since excessive exercise is often a component of the original disorder. Exercise should not be performed if severe medical problems still exist or if the person has not gained significant weight. The goal of exercise should be on improving physical fitness and health, not on burning off calories.

Treatment for Bulimia and Binge Eating Disorder

Treatment for bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder takes a multidisciplinary approach, which may include:

- Nutritional rehabilitation counseling to develop structured male plans and comfort with eating a variety of foods.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to identify unhealthy thought patterns and change behavioral responses. CBT is very effective for treating bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorders. After eating issues improve, individual or group psychodynamic therapy ("talk therapy") can be helpful.

- Drug therapy is often used along with CBT. A selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant is typically the first treatment choice.

Outpatient treatment is recommended for most people with these eating disorders. People with bulimia nervosa rarely need hospitalization except under the following circumstances:

- Binge-purge cycles have led to anorexia

- Drugs are needed for withdrawal from purging

- Major depression is present

Medications for Bulimia Nervosa and Binge Eating Disorder

Antidepressants

The most common antidepressants prescribed for bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as:

- Fluoxetine (Prozac, generic)

- Sertraline (Zoloft, generic)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, generic)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox, generic)

Studies have shown mixed results on whether SSRIs offer an additional advantage in reducing binge eating as compared to CBT. Fluoxetine has been approved for bulimia and is considered the drug of choice, although some studies suggest that other SSRIs work just as well. Other types of antidepressants, such as tricyclics, MAO inhibitors, and bupropion (Wellbutrin, generic), carry more risks for side effects than SSRIs and do not appear to be effective for treatment of bulimia.

Antidepressants may increase the risks for suicidal thoughts and actions during the first few months of treatment. In particular, adolescents and young adults should be carefully monitored during this time period for any changes in behavior.

Lisdexamfetamine

Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (Vyvanse) is approved to treat binge eating disorder. Lisdexamfetamine is a central nervous stimulant that was previously approved to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. In clinical trials, the drug reduced the number of binge eating episodes and obsessive-compulsive eating behaviors. Side effects include dry mouth, insomnia, increased heart rate, and anxiety. This drug is classified as a controlled substance because it has a high potential for abuse and dependency

Topiramate

The antiepileptic drug topiramate (Topamax, generic) has been shown in studies to reduce bingeing and purging episodes in people with bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder. However, this drug can cause serious side effects including birth defects. In addition, because people tend to lose weight while taking topiramate, it should not be used by those who have low or even normal body weight.

Psychotherapy

Eating disorders are nearly always treated with some form of psychotherapy. Depending on the individual and the disorder, certain psychological approaches may work better than others.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) works on the principle that a pattern of false thinking and belief about one's body can be recognized objectively and altered, thereby changing the response and eliminating the unhealthy reaction to food. CBT is proven to be particularly effective for bulimia nervosa.

A CBT approach for bulimia nervosa may include:

- During the initial sessions, you build up to a regular eating schedule of 3 meals a day and scheduled snacks, including foods you may have previously avoided.

- Keep a diary of your eating patterns, noting any unhealthy reactions and negative thoughts toward eating. Record any relapses (binges or purging) and the triggers that may have prompted them.

- As treatment progresses, your therapist will assign you exercises to help change your behavioral response to unhelpful thought patterns and external triggers. You will work with your therapist to construct goals and rewards for maintaining positive thoughts and behaviors.

Interpersonal Therapy

Interpersonal therapy deals with depression or anxiety that might underlie the eating disorders along with social factors that influence eating behavior. This therapy does not deal with weight, food, or body image at all.

The goals are to:

- Express feelings.

- Discover how to tolerate uncertainty and change.

- Develop a strong sense of individuality and independence.

- Address any relevant sexual issues or traumatic or abusive event in the past that might be a contributor of the eating disorder.

Motivational Enhancement Therapy

Motivational enhancement therapy is another form of behavioral therapy that uses an empathetic approach to help people understand and change their behaviors concerning food. It may be offered in an individual or group setting.

Focal Psychodynamic Therapy

Focal psychodynamic therapy (FPT) focuses on how unresolved early childhood experiences may play a role in the later development of eating disorders. The therapist helps the patient gain insight into how certain stresses and conflicts in a person's early years may have created emotional patterns and negative ways of thinking that lie beneath the eating disorder. This therapy has been found to be helpful in treating people with anorexia nervosa.

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) incorporates mindfulness, acceptance skills, interpersonal skills, and emotional regulation. It focuses on the role of emotions and how people may use food as an inappropriate coping strategy for dealing with emotional distress. A DBT therapist will work with people to help them find more effective ways to deal with emotional stressors. DBT appears to be an effective psychotherapy for people with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, and other mental health conditions associated with impulsiveness.

Family Therapy

Because a person's eating disorder affects the entire family, family therapy can be an important component of recovery. It can help all family members better understand the complex nature of eating disorders, improve their communication skills with one another, and teach strategies for coping with stress and negative feelings. Family-based psychotherapies are also integral parts of nutritional rehabilitation counseling programs, such as the Maudsley approach.

Resources

- National Institute of Mental Health -- www.nimh.nih.gov

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics -- www.eatright.org

- The American Psychiatric Association -- www.psychiatry.org/

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry -- www.aacap.org

- National Eating Disorders Association -- www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/

- National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders -- www.anad.org

- Academy for Eating Disorders -- www.aedweb.org

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Campbell K, Peebles R. Eating disorders in children and adolescents: state of the art review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):582-592. PMID: 25157017 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25157017.

Castillo M, Weiselberg E. Bulimia nervosa/purging disorder. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2017;47(4):85-94. PMID: 28532966 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28532966.

Crow SJ. Pharmacologic treatment of eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(2):253-262. PMID: 31046927 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31046927.

Espie J, Eisler I. Focus on anorexia nervosa: modern psychological treatment and guidelines for the adolescent patient. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2015;6:9-16. PMID: 25678834 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25678834.

Fisher CA, Skocic S, Rutherford KA, Hetrick SE. Family therapy approaches for anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;5:CD004780. PMID: 31041816 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31041816.

Gibson D, Workman C, Mehler PS. Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(2):263-274. PMID: 31046928 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31046928.

Gorrell S, Loeb KL, Le Grange D. Family-based treatment of eating disorders: A narrative review. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(2):193-204. PMID: 31046922 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31046922.

Harrington BC, Jimerson M, Haxton C, Jimerson DC. Initial evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(1):46-52. PMID: 25591200 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25591200.

Hay PJ, Touyz S, Claudino AM, Lujic S, Smith CA, Madden S. Inpatient versus outpatient care, partial hospitalisation and waiting list for people with eating disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD010827. PMID: 30663033 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30663033.

Katzman DK, Kearney SA, Becker AE. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 9.

Kornstein SG, Kunovac JL, Herman BK, Culpepper L. Recognizing binge-eating disorder in the clinical setting: A review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(3). PMID: 27733955 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27733955.

Lock J, La Via MC; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Committee on Quality Issues (CQI). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(5):412-425. PMID: 25901778 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25901778.

Ozier AD, Henry BW; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition intervention in the treatment of eating disorders. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(8):1236-1241. PMID: 21802573 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21802573.

Sachs KV Harnke B, Mehler PS, Krantz MJ. Cardiovascular complications of anorexia nervosa: A systematic review. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49(3):238-248. PMID: 26710932 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26710932.

Sangvai D. Eating disorders in the primary care setting. Prim Care. 2016;43(2):301-312. PMID: 27262009 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27262009.

Sysko R, Glasofer DR, Hildebrandt T, et al. The eating disorder assessment for DSM-5 (EDA-5): development and validation of a structured interview for feeding and eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(5):452-463. PMID: 25639562 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25639562.

Treasure J, Cardi V. Anorexia nervosa, theory and treatment: where are we 35 years on from Hilde Bruch's Foundation Lecture? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25(3):139-147. PMID: 28402069 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28402069.

Waller G, Raykos B. Behavioral interventions in the treatment of eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2019;42(2):181-191. PMID: 31046921 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31046921.

|

Review Date:

9/2/2019 Reviewed By: Ryan James Kimmel, MD, Medical Director of Hospital Psychiatry at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |