Stroke - InDepth

Highlights

Signs of Stroke

The American Stroke Association advises everyone to learn to recognize these signs of stroke:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of the face, arm or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden, severe headache with no known cause

F.A.S.T.

The acronym F.A.S.T. is an easy way to remember signs of stroke and what to do if you think a stroke has occurred. (The most important is to immediately call 9-1-1 for emergency assistance.) F.A.S.T. stands for:

- FACE. Ask the person to smile. Check to see if one side of the face droops.

- ARMS. Ask the person to raise both arms. See if one arm drifts downward.

- SPEECH. Ask the person to repeat a simple sentence. Check to see if words are slurred and if the sentence is repeated correctly.

- TIME. If a person shows any of these symptoms, time is essential. It is important to get to the hospital as quickly as possible. Call 9-1-1. Act F.A.S.T.

Treatment of Acute Stroke

It is critical for people with stroke symptoms to get to a hospital as quickly as possible. People who are suffering an ischemic stroke may be able to receive a clot-busting drug called tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to dissolve the clot if they reach a hospital within 3 to 4.5 hours of symptom onset. Ideally, people should receive the clot-busting drug within 60 minutes of arriving at the hospital. But this treatment window can be extended to 4.5 hours for people who:

- Are younger than age 80 years

- Are not having a severe stroke

- Do not have a history of stroke and diabetes

- Do not take oral anticoagulant ("blood-thinner") drugs

Recently, so called 'stent retrievers' have been introduced in patients with acute embolic stroke. These devices can be threaded into the blocked artery for removal of the clot or thrombus in a procedure called mechanical thrombectomy. This treatment also works better the earlier it is provided.

Stroke Prevention for Women

In 2014, the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association released the first guidelines to specifically address stroke prevention in women. Some of the unique risks that doctors need to consider in women include:

- Migraine with aura, which occurs more frequently in women than men.

- Preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related condition marked by dangerously high blood pressure.

- Oral contraceptive (birth control pill) use, which becomes even riskier for women who smoke, have high blood pressure, or are older.

Introduction

A stroke is the sudden death of brain cells due to lack of oxygen. A stroke is usually defined as one of 2 types:

- Ischemic (caused by a blockage in an artery)

- Hemorrhagic (caused by a tear in the artery's wall that produces bleeding into or around the brain)

The consequences of a stroke, the type of functions affected, and the severity depend on where in the brain it has occurred and the extent of the damage.

Blood Flow Blockage

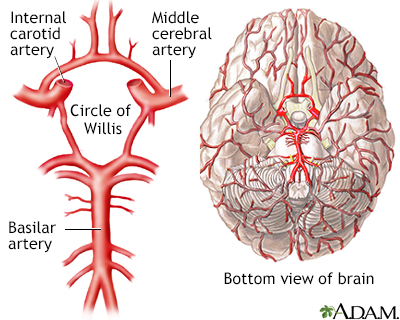

Strokes are caused by either blood flow blockage to the brain (ischemic stroke) or the sudden rupture of an artery in the brain (hemorrhagic stroke). Sometimes an ischemic stroke can become a hemorrhagic stroke when bleeding follows the acute blockage. Brain cells require a constant supply of oxygen to stay healthy and function properly. Therefore, blood is supplied continuously to the brain through two main arterial systems:

- The carotid arteries come up through either side of the front of the neck. (To feel the pulse of a carotid artery, place your fingertips gently against either side of your neck, right under the jaw.)

- The basilar artery forms at the base of the skull from the vertebral arteries, which run up along the spine, join, and come up through the rear of the neck.

The Circle of Willis is the joining area of several arteries at the bottom (inferior) side of the brain. At the Circle of Willis, the internal carotid arteries branch into smaller arteries that supply oxygenated blood to over 80% of the brain.

Blockage of blood flow to the brain for even a short period of time can be disastrous and cause brain damage or even death.

Ischemic Stroke

Ischemic strokes are by far the more common type of stroke, causing nearly 90% of all strokes. Ischemia means the deficiency of oxygen in vital tissues. Ischemic strokes are caused by blood clots that are usually one of four types.

Thromboembolic Stroke and Atherosclerosis

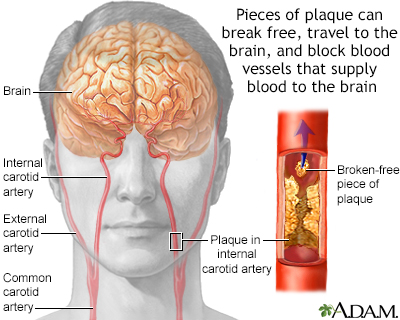

An embolic stroke is caused by a dislodged blood clot that has traveled through the blood vessels (an embolus) until it becomes wedged in an artery. The vast majority of ischemic strokes are caused by this mechanism. These types of ischemic stroke usually occur when an artery that carries blood to the brain is blocked by a thrombus (blood clot) that forms as the result of atherosclerosis (commonly known as hardening of the arteries). These strokes are also sometimes referred to as large-artery strokes. The process leading to thrombotic stroke is complex and occurs over time:

- The arterial walls slowly thicken, harden, and narrow until blood flow is reduced, a condition known as stenosis.

- As these processes continue, blood flow slows.

In addition, other events contribute to the coming stroke:

- The artery is narrowed by a cholesterol-laden plaque that becomes susceptible to tearing. In this event, a thrombus (blood clot) forms.

- The blood clot then breaks off and travels to the brain, where it blocks an artery and shuts off oxygen to part of the brain. A stroke occurs.

Cardioembolic Strokes and Atrial Fibrillation

Cardioembolic strokes start with clots in the heart and may be due to various conditions:

- In many cases, the blood clots originally form as a result of a heart rhythm disorder known as atrial fibrillation.

- Emboli can also originate from blood clots that form at the site of artificial heart valves.

- People with heart valve disorders such as mitral stenosis are at increased risk for clots when they also have atrial fibrillation.

- Emboli can also occur after a heart attack or in association with heart failure.

- Rarely, emboli are formed from fat particles, tumor cells, or air bubbles that travel through the bloodstream.

Thrombotic Strokes

Thrombotic strokes occur when a clot develops in a diseased artery right in the brain. Thrombotic strokes cause about 1 in 5 ischemic strokes. Thrombotic strokes tend to occur at night, and their symptoms may develop more slowly than those of an embolic stroke, which is usually swift and sudden.

Small Vessel (Lacunar) Strokes

Lacunar infarcts are very tiny ischemic strokes, which may cause clumsiness, weakness, and emotional variability. They make up the majority of silent brain infarctions and may result from chronic high blood pressure. They are actually a subtype of thrombotic stroke. They can also sometimes serve as warning signs for a major stroke.

Many older people have had silent brain (cerebral) infarctions, small strokes that cause no apparent symptoms. They are detected in up to half of the older people who undergo imaging tests for problems other than stroke. The presence of silent infarctions indicates an increased risk for future stroke, as well as dementia. Smokers and people with hypertension are at particular risk.

Stroke due to Arterial Dissection

If one of the arteries develops a tear in the lining, blood can squeeze between the layers of the artery wall, known as a dissection. As the blood expands, it closes off the lumen of the artery and prevents blood flow to parts of the brain. Dissection often occurs due to trauma to the artery but may occur in people with conditions that affect the connective tissue in the arteries.

Hypercoagulable states

Certain conditions can cause the blood to clot more than usual and can result in a stroke. These conditions can be hereditary or develop as a consequence of another medical problem such as cancer or autoimmune disease.

Vasculitis

Cerebral vasculitis results in strokes when inflammation of the blood vessel blocks blood flow. This can occur in autoimmune diseases such as lupus, or result from a reaction to medication or street drugs.

Endocarditis

Infection in the body can spread to the heart valves. Infective particles, most commonly bacterial, break off the valve and lodge in a blood vessel in the brain. This condition often causes multiple strokes. Autoimmune disease can also cause endocarditis.

Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs)

A transient ischemic attack (TIA) is an episode in which a person has stroke-like symptoms that typically last for a few minutes and usually less than 1 to 2 hours. Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are caused by tiny emboli (clots often formed of pieces of calcium and fatty plaque) that lodge in an artery to the brain. They typically break up quickly and dissolve. But they do temporarily block the supply of blood to the brain.

TIAs do not cause lasting damage. But they are a warning sign that a true stroke may happen in the future if something is not done to prevent it. TIA should be taken very seriously and treated as aggressively as a stroke. About 10% to 15% of people who have a TIA have a stroke within 3 months, with half of these strokes occurring within 48 hours after the TIA.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

About 10% of strokes occur from hemorrhage (sudden bleeding) into or around the brain. While hemorrhagic strokes are less common than ischemic strokes, they tend to be more deadly.

Hemorrhagic strokes are categorized by how and where they occur.

- Parenchymal, or intracerebral, hemorrhagic strokes. These strokes occur from bleeding within the brain tissue. They are most often the result of high blood pressure exerting excessive pressure on arterial walls already damaged by atherosclerosis. Heart attack patients who have been given drugs to break up blood clots or blood-thinning drugs have a slightly increased risk for this type of stroke. Bleeding may also occur if there is an underlying brain abnormality, such as a tumor or infection.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhagic strokes. This kind of stroke occurs when a blood vessel on the surface of the brain bursts, leaking blood into the subarachnoid space, an area between the brain and the skull. They are usually caused by the rupture of an aneurysm, a bulge in a blood vessel, which creates a weakening in the artery wall.

- Arteriovenous malformation (AVM). Is an abnormal connection between arteries and veins. If it occurs in the brain and ruptures, it can also cause a hemorrhagic stroke.

Risk Factors

On average, every 40 seconds, someone in the United States has a stroke. While age is the major risk factor, people who have a stroke are likely to have more than one risk factor.

Overall Cardiovascular Risk

Doctors can calculate an individual person's risk of having a stroke or heart attack within the next 10 years. The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have a special "risk calculator" that factors into its equation a person's race, sex, age, total cholesterol, HDL ("good") cholesterol, blood pressure, use of blood pressure medications, diabetes status, and smoking history. These are the critical risk factors for both stroke and heart attack.

The ACC/AHA recommend using this risk equation to calculate 10-year risk in people, ages 40 to 79 years old. A separate calculation is used to estimate lifetime risk for heart attack or stroke in people starting at age 20 years.

Age

People most at risk for stroke are older adults, particularly those who have high blood pressure, are sedentary, are overweight, smoke, or have diabetes. Older age is also linked with higher rates of post-stroke dementia. However, younger people are not immune. Many stroke victims are under age 65.

Sex

In most age groups, except older adults, stroke is more common in men than in women. However, stroke kills and disables more women than men. This may be partly due to the fact that women tend to live longer than men, and stroke is more common among older adults.

Younger women have specific risk factors that place them at greater risk for stroke than men. These risks include migraine with aura, use of oral contraceptives, and pregnancy-related high blood pressure. Hypertension during pregnancy can develop into a dangerous condition called preeclampsia that increases stroke risk. Smoking amplifies these risks, as does the presence of high cholesterol or obesity.

Race and Ethnicity

Some US populations, including African Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Hispanics, have a higher risk of stroke than non-Hispanic Whites. African Americans have a significantly higher risk of death from stroke and double the risk of a first stroke compared with non-Hispanic Whites. Younger African Americans are two to three times more likely to have a stroke than similar age white people and four times more likely to die from one.

The racial disparities in stroke incidence may be partly explained by the higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure in these groups. However, studies suggest that socioeconomic factors also affect these differences.

Family History

A family history of stroke or TIA is a strong risk factor for stroke.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking

People who smoke a pack of cigarettes a day have more than twice the risk for stroke as nonsmokers. Smoking increases both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke risk. The risk for stroke may remain elevated for as long as 14 years after quitting, so the earlier one quits the better.

Diet

Unhealthy diet (saturated fat, high sodium) can contribute to heart disease, high blood pressure, and obesity, which are all risk factors for stroke. A heart-healthy diet can reduce the risk for stroke.

Physical Inactivity

Lack of regular exercise can increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, and poor circulation, which increases the risk of stroke.

Alcohol and Drug Abuse

Alcohol abuse, including binge drinking, increases the risk of stroke. Drug abuse, particularly with cocaine or methamphetamine, is a major risk factor for stroke in young adults. Anabolic steroids, used for body-building and sports enhancement, also increase stroke risk.

Heart and Vascular Diseases

Heart disease and stroke are closely tied for many reasons. People who have one heart or vascular condition (such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart disease, diabetes, or peripheral artery disease) are at increased risk for developing other related conditions.

Prior Stroke

A history of a prior stroke or TIA significantly increases the risk for a subsequent stroke. People who have had at least one TIA are 10 times more likely to have a stroke than those who have not had a TIA.

Prior Heart Attack

People who have had a heart attack are at increased risk of stroke.

High Blood Pressure

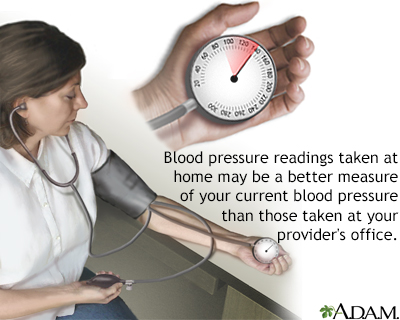

High blood pressure (hypertension) contributes to about 70% of all strokes. People with hypertension have up to 10 times the normal risk of stroke, depending on the severity of the blood pressure and the presence of other risk factors. Women with hypertension are at greater risk than men for having a first stroke.

Hypertension is also an important cause of so-called silent cerebral infarcts (mini-strokes caused by blockages in the blood vessels in the brain), which may predict major stroke. Controlling blood pressure is extremely important for stroke prevention. Normal blood pressure is below 120/80 mmHg. Blood pressure is considered elevated between 120/80 and 129/80 mmHg and high at 130/80 mmHg or above.

Unhealthy Cholesterol Levels

A high total cholesterol level increases the risk of developing atherosclerosis ("hardening of the arteries") and heart disease. In atherosclerosis, fatty deposits (plaques) of cholesterol build up in the arteries of the heart.

Heart Disease

Coronary artery disease (heart disease), the end result of atherosclerosis, increases stroke risk. Anti-clotting medications, which are used in heart disease treatment to break up blood clots, can increase the risk of hemorrhagic stroke.

Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation, a major risk factor for stroke, is a heart rhythm disorder in which the atria (the upper chambers in the heart) do not beat in a coordinated fashion, which often makes the overall heart rate fast and irregular. The blood stagnates instead of being pumped out promptly, increasing the risk for formation of blood clots that break loose and travel toward the brain or other parts of the body.

The stroke risk for people with atrial fibrillation is generally highest for those older than age 75, with heart failure or enlarged heart, coronary artery disease or other atherosclerotic vascular diseases, history of blood clots, diabetes, hypertension, women, or those with heart valve abnormalities.

Structural Heart Problems

Dilated cardiomyopathy (enlarged heart), heart valve disorders, and congenital heart defects, such as patent foramen ovale (opening between the upper chambers of heart, called atria) and atrial septal aneurysm (bulging of wall between the atria), are risk factors for stroke.

Carotid Artery Disease and Peripheral Artery Disease

Carotid artery disease is a serious risk factor for stroke. Atherosclerosis can cause fatty build-up in the carotid arteries of the neck, which can lead to blood clots that block blood flow and oxygen to the brain. People with peripheral artery disease, which occurs when atherosclerosis narrows blood vessels in the legs and arms, are at increased risk of carotid artery disease and subsequently stroke.

Hypertension is a disorder characterized by chronically high blood pressure. It must be monitored, treated, and controlled by medication, lifestyle changes, or a combination of both.

Diabetes

Heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death in people with diabetes. Diabetes is second only to high blood pressure as the main risk factor for ischemic stroke. The risk is highest for adults newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and patients with diabetes who are younger than age 55. African-Americans with diabetes are at an even higher risk for stroke at a younger age. Diabetes is strongly associated with other stroke risk factors such as obesity and high blood pressure. Diabetes does not appear to increase the risk for hemorrhagic stroke.

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity is associated with stroke risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and unhealthy cholesterol levels. Obesity may also increase the risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke independently of these other risk factors. Weight that is centered around the abdomen (the so-called apple shape) has a particularly high association with stroke, as it does for heart disease, in comparison to weight distributed around hips (pear-shape).

Obesity is particularly hazardous when it is one of the components of metabolic syndrome. This syndrome is diagnosed when at least three of the following conditions are present: abdominal obesity, low HDL cholesterol, high triglyceride levels, high blood pressure, and insulin resistance. Because metabolic syndrome is a pre-diabetic condition that is significantly associated with heart disease, people with this syndrome are at increased risk for stroke even before diabetes develops. Lifestyle modifications (diet, exercise, weight loss) can help reduce the risk for stroke in people diagnosed with metabolic syndrome.

Other Risk Factors

Migraine

Studies suggest that migraine headache is a risk factor for stroke in both men and women, especially before age 50. The risk is higher for migraine accompanied by aura, which occur more frequently in women. Women who have migraine with aura and also smoke, or use oral contraceptives, have even greater risks for ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke.

Oral Contraceptives

Birth control pills, which contain estrogen, can increase stroke risk, especially for women who are older, have high blood pressure, or who smoke. The American Heart Association recommends that doctors screen patients for high blood pressure before prescribing oral contraceptives.

Pregnancy

For most women, pregnancy carries a very small risk for stroke. However, women who have high blood pressure (hypertension) during pregnancy have an increased risk for stroke. Hypertension during pregnancy can lead to preeclampsia, a dangerous condition marked by high blood pressure and increased protein in the urine. Preeclampsia is a risk factor for future hypertension and stroke, as is gestational diabetes (insulin resistance that occurs during late pregnancy). The post-partum period has the greatest risk for stroke.

The American Heart Association recommends that women who have high blood pressure during pregnancy or are at risk for preeclampsia be treated with daily low-dose aspirin until the time of delivery. A daily calcium supplement may also help prevent preeclampsia for women who do not consume enough calcium in their diets.

Erectile dysfunction

Men who have erectile dysfunction have a higher risk of stroke (both ischemic and hemorrhagic) than men without erectile dysfunction.

Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea is a common sleep disorder that occurs when tissues in the upper airways come too close to each other during sleep, temporarily blocking the inflow of air. People with untreated sleep apnea are at increased risk for many heart problems, including stroke. Current guidelines recommend screening and treating sleep apnea in people who have had a stroke or TIA.

Sickle Cell Disease

People with sickle cell disease are at increased risk for stroke at a young age.

Depression

Some research suggests that depression may increase the risk for stroke.

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic) and diclofenac (Cataflam, Voltaren, generic) may increase the risk of stroke, especially for patients who have other stroke risk factors.

Prognosis

Stroke is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States. However, mortality rates are declining. Over 75% of people survive a first stroke during the first year, and over half survive beyond 5 years.

Severity of an Ischemic Versus Hemorrhagic Stroke

People who suffer ischemic strokes have a much better chance for survival than those who have hemorrhagic strokes. Among the ischemic stroke categories, the greatest dangers are posed by embolic strokes, followed by thrombotic and lacunar strokes.

Hemorrhagic stroke not only destroys brain cells, it also poses other complications, including increased pressure on the brain or spasms in the blood vessels, both of which can be very dangerous. However, studies suggest that survivors of hemorrhagic stroke have a greater chance for recovering function than those who survive ischemic stroke.

Long-Term Complications and Disabilities

Many people are left with physical weakness and often have accompanying pain and spasticity (muscle stiffness or spasms). Depending on the severity of the symptoms and how much of the body is involved, these impairments can affect the ability to walk, to rise from a chair, to feed oneself, to speak, write or use a computer, to drive, and to perform many other activities.

Factors that Affect Quality of Life in Survivors

Many stroke survivors recover functional independence after a stroke. But 25% are left with a minor disability, and 40% experience moderate-to-severe disabilities. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has a stroke scale that helps predict the severity and outcome of a stroke by scoring 11 factors:

- Levels of consciousness

- Gaze

- Visual fields

- Facial movement

- Motor functions in the arm

- Motor functions in the leg

- Coordination

- Sensory loss

- Problems with language

- Inability to articulate

- Attention

People with ischemic strokes who score less than 10 have a favorable outlook after a year. Only 4% to 16% of people do well if their score is more than 20.

Factors Affecting Recurrence

The risk for recurring stroke is highest within the first few weeks and months of the previous stroke. But about 25% of people who have a first stroke will go on to have another stroke within 5 years. Risk factors for recurrence include:

- Older age

- Evidence of blocked arteries (a history of coronary artery disease, carotid artery disease, peripheral artery disease, ischemic stroke, or TIA)

- Hemorrhagic or embolic stroke

- Diabetes

- Alcoholism

- Valvular heart disease

- Atrial fibrillation

Symptoms

People at risk and partners or caretakers of people at risk for stroke should be aware of its typical symptoms. The stroke victim should get to the hospital as soon as possible after these warning signs appear. It is particularly important for people with migraines or frequent severe headaches to understand how to distinguish between their usual headaches and symptoms of a stroke.

Time is of the essence in treating stroke. Studies show that people receive faster treatment for stroke if they arrive by ambulance rather than coming to the emergency room on their own. People should immediately call 9-1-1 for emergency assistance if they have any warning signs of stroke:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of the face, arm, or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Sudden confusion, trouble speaking or understanding

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden, severe headache with no known cause

An easy way to remember the signs of stroke, and what to do, is by the acronym F.A.S.T. If you think you or someone else is having a stroke, the National Stroke Association's F.A.S.T. test advises:

- FACE. Ask the person to smile. Check to see if one side of the face droops.

- ARMS. Ask the person to raise both arms. See if one arm drifts downward.

- SPEECH. Ask the person to repeat a simple sentence. Check to see if words are slurred and if the sentence is repeated correctly.

- TIME. If a person shows any of these symptoms, time is essential. It is important to get to the hospital as quickly as possible. Call 9-1-1. Act F.A.S.T.

Symptoms of TIAs and Early Ischemic Stroke

The symptoms of a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and early ischemic stroke are similar. However, in the case of a TIA, the symptoms resolve and there is no evidence for infarction (brain cell death), for example on an imaging test (CT or MRI). Symptoms depend on where the injury in the brain occurs. The origin of the stroke is usually either the carotid or basilar arteries.

The build-up of plaque in the internal carotid artery may lead to narrowing and irregularity of the artery's lumen, preventing proper blood flow to the brain. More commonly, as the narrowing worsens, a clot forms, then pieces of clot break free, travel to the brain, and block blood vessels that supply blood to the brain. This leads to stroke, with possible paralysis or other deficits.

Symptoms From Blockage in the Carotid Arteries

The carotid arteries branch off of the aorta (the primary artery leading from the heart) and lead up through the neck, around the windpipe, and into the brain. When TIAs or strokes result from clots that form on blockages in the carotid artery, symptoms may occur in either the retina of the eye or the cerebral hemisphere (the large top part of the brain).

Symptoms include:

- When oxygen to the eye is reduced, people describe the visual effect as a shade being pulled down. People may develop poor night vision. About 35% of TIAs are associated with temporary lost vision in one eye. The visual impairment occurs on the same side as the carotid disease.

- When the cerebral hemisphere is affected, a person can have problems with speech and partial and temporary paralysis, drooping eyelid, tingling, and numbness, usually on one side of the body. The stroke victim may be unable to express thoughts verbally or to understand spoken words. If the stroke injuries are on the right side of the brain, the symptoms will develop on the left side of the body and vice versa.

- Uncommonly, people may have seizures.

Symptoms From Blockage in the Basilar Artery

The basilar artery is formed at the base of the skull from the vertebral arteries, which run up along the spine and join at the back of the head. When stroke or TIAs originate here, both hemispheres of the brain may be affected so that symptoms occur on both sides of the body. The following symptoms may develop:

- Temporarily dim, gray, blurry, or lost vision, usually in both eyes

- Tingling or numbness in the mouth, cheeks, or gums

- Headache, usually in the back of the head

- Dizziness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Difficulty swallowing

- Slurring words

- Weakness in the arms and legs, sometimes causing a sudden fall

- Double vision

- Unconsciousness or coma

Such strokes usually occur in the brain stem, which can have profound effects on breathing, blood pressure, heart rate, and other vital functions, but may have no effect on thinking or language.

Speed of Symptom Onset

The speed of symptom onset of a major ischemic stroke may indicate its source:

- If the stroke is caused by an embolus (a clot that has traveled to an artery in the brain), the onset is sudden. Headache and seizures can occur within seconds of the blockage.

- When thrombosis (a blood clot that has formed within the brain) causes the stroke, the onset usually occurs more gradually, over minutes to hours. On rare occasions it progresses over days to weeks.

Symptoms of Hemorrhagic Stroke

Intracerebral Hemorrhage Symptoms

Symptoms of an intracerebral, or parenchymal, hemorrhage typically begin very suddenly, evolve over several hours, and include:

- Severe headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Altered mental states

- Seizures

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

When the hemorrhage is a subarachnoid type, warning signs may occur from the leaky blood vessel a few days to a month before the aneurysm fully develops and ruptures. Warning signs may include:

- Sudden onset of severe headache.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Sensitivity to light.

- Various neurologic abnormalities. Seizures, for example, occur in about 8% of people.

When the aneurysm ruptures, the stroke victim may experience:

- A terrible headache

- Neck stiffness

- Vomiting

- Altered states of consciousness

- Eyes may become fixed in one direction or lose vision

- Stupor, rigidity, and coma

Diagnosis

A diagnostic work-up for stroke includes physical and neurological examinations, patient's medical history, blood tests (to measure blood glucose levels, blood coagulation time, cardiac enzymes, and other factors), and imaging tests. Many of the same procedures are used to diagnose a stroke and to evaluate the risk of future major stroke in people who have had a transient ischemic attack (TIA).

For people who have suffered a stroke, the first step is to determine as quickly as possible whether the stroke is ischemic (caused by blood clot blockage) or hemorrhagic (caused by bleeding). A CAT scan of the head is done as soon as possible. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), also known as a clot-busting drug therapy, can be life-saving for ischemic stroke patients. The sooner tPA is administered intravenously, the more likely a person is to benefit and the medicine must be given no later than 3 to 4 ½ hours after the stroke starts. However, if the stroke is caused by a hemorrhage, thrombolytic drugs will increase the bleeding and can be lethal.

Time is a critical factor in treating stroke. Doctors do not want to delay treatment too long by doing too many diagnostic tests. When a person arrives in the emergency department, the doctor may recommend one or more of the following tests:

- Physical and medical exam to ask patient or family member about symptoms, time of symptom onset, risk factors, and any medications the patient is currently taking

- Blood tests to check blood sugar (glucose levels), electrolytes, blood platelet count, and other factors

- Imaging tests such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- CT angiogram or angiogram

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG) to evaluate heart function

Because therapy must be administered so quickly, usually only a CT scan is done before treatment starts. A CT angiogram is often done at the same time as the CT since it can determine the presence of blood clots. People on blood thinners or who have bleeding problems may need blood work before they can be treated with tPA.

Laboratory Tests

Several different types of blood tests are used to determine the patient's condition. They include blood tests for:

- Blood sugar (glucose) levels; this is the only blood test that must be performed before clot-buster treatment.

- Electrolytes and kidney function tests.

- Complete blood count, including platelets.

- Blood clotting time.

- Cardiac enzymes such as troponin.

- In young people and those with no risk factors for stroke, blood tests may be done to see if there is an abnormal tendency for blood clots.

Imaging Tests

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are the standard imaging tests to diagnose strokes. They help distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. These tests can show signs of bleeding and can also help indicate whether a stroke is recent.

MRIs are also the preferred imaging technique for evaluating patients with probable TIA and can detect very tiny hemorrhages. However, an MRI can take longer to perform than a CT and is sometimes not as widely available. For these reasons, a CT scan may be used as the initial imaging test instead of MRI.

CT and MR perfusion

These tests use special software with a CT or MRI scan to determine the amount of brain injury that may be permanent.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography and Computerized Tomography Angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and computerized tomography angiography (CTA) of the head and neck are noninvasive ways of evaluating the carotid arteries and the arteries in the brain. In many situations, these tests can be used instead of cerebral angiography.

CTA or MRA are recommended ahead of treating an ischemic stroke with a method called mechanical thrombectomy. In some stroke centers, specialized imaging called CT perfusion better identifies people who are more likely to benefit from treatment.

Carotid Ultrasound

Carotid ultrasound procedures are valuable tools for measuring the width of the artery and how the blood flows through it. Carotid ultrasounds can help determine the severity of plaque build-up and narrowing and blocking of the carotid arteries (carotid stenosis).

In carotid ultrasounds, high-frequency sound waves are directed from a hand-held transducer probe to the target area. These waves "echo" off the arterial structures and produce a two-dimensional image on a monitor, which will make obstructions or narrowing of the arteries visible. As most people get thorough imaging of their carotid arteries with CT or MRI, ultrasound has a limited role in stroke treatment. Ultrasound also does not provide information about the basilar or vertebral arteries.

Cerebral Angiography

Cerebral angiography is an invasive procedure that may be used for patients with stroke or TIAs who may need a procedure. It requires the insertion of a catheter into the groin, which is then threaded up through the arteries to the base of the carotid artery. At this point, a dye is injected, and x-rays, CTs, or MRI scans determine the location and extent of the narrowing, or stenosis, of the artery.

Transcranial Doppler

This is an ultrasound test that can detect narrowing of the blood vessels within the skull. It is also non-invasive but is not used as commonly.

Heart Evaluation

Electrocardiogram

A heart evaluation using an electrocardiogram (ECG) is important in any patient with a stroke or suspected stroke. An ECG records the electrical current in the heart muscle. It may detect arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation (a major cause of stroke) or give clues as to other heart problems.

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram uses ultrasound to view the chambers and valves of the heart. It is generally useful for stroke patients to identify blood clots or risk factors for blood clots that can travel to the brain and cause stroke. There are two types of echocardiograms:

- Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) views the heart through the chest. It is noninvasive and is the standard approach.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) examines the heart using an ultrasound tube that the patient swallows and passes down the throat. It is uncomfortable and requires sedation. It is typically used to obtain more accurate images of certain parts of the heart and aorta. TEE is more likely to be used when there is no likely cause of stroke identified with less invasive testing, particularly in younger people.

ABCD2 Score

People who have a TIA are at increased risk for a major stroke in the days and weeks that follow. The ABCD2 score is a tool that helps doctors predict short-term stroke risk following a TIA. The ABCD2 score assigns points for various factors, including:

- Age (over 60 years)

- Blood pressure (greater or equal to 140/90 mm Hg)

- Clinical features (weakness on one side of the body, speech impairment without weakness)

- Duration of TIA symptoms (at least 60 minutes)

- Diabetes

Based on the number of points, a doctor can identify whether a patient is at low, moderate, or high risk of having a stroke within 2 days after a TIA. The ABCD2 score can help doctors better decide which people need hospitalization and emergency care.

Treatment

A stroke requires immediate emergency treatment. It is critical to get to the hospital and be diagnosed as soon as possible. There are several steps in the initial assessment and management of stroke.

Receiving treatment early is essential in reducing the damage from a stroke. The chances for survival and recovery are also best if treatment is received at a hospital specifically certified as a primary stroke center.

Treatment of Ischemic Stroke

Immediate treatment of ischemic stroke aims at dissolving the blood clot. People who arrive at the emergency room with signs of acute ischemic stroke are usually given aspirin to help thin the blood. Aspirin can be lethal for people suffering a hemorrhagic stroke, so it is best not to take aspirin at home and to wait until after the doctor has determined what kind of stroke has occurred. If a person might need other treatment like tPA, aspirin may be avoided.

If people can be treated within 3 to 4.5 hours of stroke onset (when symptoms first appear), they may be candidates for thrombolytic ("clot-buster") drug therapy. Thrombolytic drugs are used to break up existing blood clots. The standard thrombolytic drugs are tissue plasminogen activators (tPAs). They include alteplase (Activase) and tenecteplase (TNKase).

The following steps are critical before injecting a clot-buster drug:

- Before the thrombolytic is given, a CT scan must first confirm that the stroke is not hemorrhagic. If the stroke is ischemic, a CT scan can also suggest if injuries are very extensive, which might affect the use of thrombolytics. A blood glucose measurement should also be performed.

- Thrombolytics should generally be administered within 3 hours of a stroke. Best results are achieved if patients are treated within 60 minutes of arriving at the hospital.

- According to guidelines from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association, some patients may benefit from treatment with a thrombolytic within 4.5 hours after stroke symptoms begin. These patients include those who are younger than 80 years, are having a less severe stroke, do not have a history of stroke or diabetes, and do not take anticoagulant (blood-thinner) drugs.

- People who do not meet these criteria should probably not be treated with a thrombolytic after the 3-hour window.

Thrombolytics carry a risk for hemorrhage, so they may not be appropriate for people with existing risk factors for bleeding. Blood pressure must be controlled before and after tPA is given. If the blood pressure is too high, there is great risk of bleeding after tPA.

A clot-buster drug is usually administered through an intravenous injection. Less commonly, the drug may be administered through a catheter that is inserted in the groin and threaded through to the arteries in the brain (a procedure called intra-arterial thrombolysis).

Another alternative treatment for clot removal is called mechanical thrombectomy. It uses a self-expanding stent (wire mesh) called a stent retriever to capture and retrieve the clot. The device is inserted into the blocked artery through a catheter and then removed along with the clot.

Before mechanical thrombectomy, an urgent imaging test like CT angiogram or magnetic resonance (MR) angiogram is recommended.

Specific criteria are used to determine which patients are candidates for mechanical thrombectomy. Benefit appears to be highest in selected people who:

- Have received thrombolytic therapy within 4 to 5 hours of onset of symptoms.

- Have blockage of the internal carotid artery, the middle or anterior cerebral arteries, and their larger branches.

- Were able to receive treatment within 6 hours after symptoms began. This window is extended to 16 to 24 hours for certain people with large vessel occlusion.

Treatment of Hemorrhagic Stroke

Treatment of hemorrhagic stroke depends in part on whether the stroke is caused by bleeding between the brain and the skull (subarachnoid hemorrhage) or within the brain tissue (intracerebral hemorrhage). Both medications and surgery may be used.

Medications

Various types of drugs are given depending on the cause of the bleeding. If high blood pressure is the cause, antihypertensive medications are administered to lower blood pressure. If anticoagulant medications such as warfarin (Coumadin, generic) or heparin are the cause, they are immediately discontinued and other drugs may be given to increase blood coagulation. Other drugs, such as the calcium channel blocker nimodipine (Nimotop), can help reduce the risk of ischemic stroke following hemorrhagic stroke.

Surgery

Surgical treatments depend on the cause of the hemorrhagic stroke:

- High blood pressure (hypertension) is one of the main causes of intracerebral hemorrhage. Bleeding in or around the brain causes swelling of brain tissue. The surgical approach is a craniotomy, which involves making an opening in the skull bone to remove excess blood and reduce pressure on the brain.

- Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are tangles of abnormal blood vessels. AVMs are the other main cause of intracerebral hemorrhage. There are several surgical techniques for repairing AVMs. They include surgery to remove the AVM or radiation therapy to shrink the AVM. Embolization treatment involves inserting a catheter into an artery in the groin and threading it through to the blood vessels in the brain. A liquid is injected into the catheter to seal off the AVM.

- Aneurysms are the main causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage. An aneurysm is a balloon-like bulge in a blood vessel. Surgery for aneurysms involves either surgical clipping or endovascular coiling. With clipping, the surgeon makes an incision in the skull and places a clamp on the aneurysm to prevent further leaking of blood into the brain. With coiling, a tiny coil is inserted into a catheter placed in the groin and threaded through to the aneurysm. Blood clots that form around this coil prevent the aneurysm from breaking open and bleeding.

An intraventricular catheter may be surgically inserted into the ventricles of the brain to relieve pressure.

Managing Stroke Complications

In the days following stroke, people are at risk for complications. The following steps are important.

Maintain Adequate Delivery of Oxygen

It is very important to maintain oxygen levels. In some cases, airway ventilation may be required. Supplemental oxygen may also be necessary for patients when tests suggest low blood levels of oxygen.

Manage Fever

Fever should be monitored and aggressively treated with medication and, if needed, a cooling blanket since its presence predicts a poorer outlook.

Evaluate Swallowing

People should have their swallowing function evaluated before they are given any food, fluid, or medication by mouth. If people cannot adequately swallow they are at risk of choking. People who cannot swallow on their own may require nutrition and fluids delivered intravenously or through a tube placed in the nose.

Maintain Electrolytes

Maintaining a healthy electrolyte balance (the ratio of sodium, calcium, and potassium in the body's fluids) is critical.

Control Blood Pressure

Managing blood pressure is essential, but complicated. Blood pressure often declines spontaneously in the first 24 hours after stroke. People whose blood pressure remains elevated should be treated carefully with antihypertensive medications.

Monitor Increased Brain Pressure

Hospital staff should watch closely for evidence of increased pressure on the brain (cerebral edema), which is a frequent complication of hemorrhagic strokes. It can also occur a few days after ischemic strokes. Early symptoms of increased brain pressure are drowsiness, confusion, lethargy, weakness, and headache. Medications such as mannitol may be given during a stroke to reduce pressure or the risk for it. An intracranial pressure (ICP) monitor may be inserted to assess the brain pressure response to treatment.

Keeping the top of the body higher than the lower part, such as by elevating the head of the bed, can reduce pressure in the brain and is standard practice for people with ischemic stroke. However, this practice also lowers blood pressure in general, which may be dangerous for people with a massive stroke.

Monitor the Heart

People must be monitored using electrocardiography to check for atrial fibrillation and other heart rhythm problems. People are at high risk for heart attack following stroke.

Control Blood Sugar (Glucose) Levels

Elevated blood sugar (glucose) levels can occur with severe stroke and may be a marker of serious trouble. People with high blood glucose levels may require insulin therapy.

Monitor Blood Coagulation

Regular tests for blood coagulation are important to make sure that the blood is not so "thick" that it will clot nor so "thin" that it causes bleeding.

Check for Deep Venous Thrombosis

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot in the veins of the lower leg or thigh. It can be a serious post-stroke complication because there is a risk of the clot breaking off and traveling to the brain or heart. DVT can also cause pulmonary embolism if the blood clot travels to the lungs. If necessary, an anticoagulant drug will be given.

Prevent Infection

People who have had a stroke are at increased risk for pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and other widespread infections.

Prevention

People who have had a first stroke or TIA are at high risk of having another stroke. Secondary prevention measures are essential to reduce this risk.

Lifestyle Changes

Quit Smoking

Smoking is a major risk factor for stroke. People should also avoid exposure to second-hand smoke.

Eat Healthy

People should make dietary changes to follow a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, high in potassium, and low in saturated fats. Everyone should limit sodium (salt) intake to less than 2,400 mg/day, and some people may benefit from limiting sodium to less than 1,500 mg/day. Sodium restriction is particularly important for people over age 50, all African-Americans, and everyone with high blood pressure. For diet plans, the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and the Mediterranean diet may be particularly good choices for reducing the risk for stroke.

Exercise

Exercise helps reduce the risk of atherosclerosis, which can help reduce the risk of stroke. Doctors recommend at least 30 minutes of exercise on most, if not all, days of the week.

Maintain Healthy Weight

People who are overweight should try to lose weight through healthy diet and regular exercise.

Limit Alcohol Consumption

Heavy alcohol use and binge drinking increase the risk of both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. If you drink, limit alcohol to no more than one drink a day for women or two drinks a day for men.

Antiplatelet Medications for Preventing Stroke

Your doctor may suggest taking aspirin or, if you cannot take aspirin, another antiplatelet drug such as clopidogrel (Plavix, generic) or ticagrelor (Brilinta) to help prevent blood clots from forming in your arteries or your heart. These medicines are called antiplatelet drugs. These drugs make blood platelets less sticky and therefore less likely to form a clot. You should never start or stop taking aspirin without first talking to your doctor.

Primary Prevention (to prevent a first stroke)

Primary prevention is when antiplatelet drugs are taken before a stroke or a TIA has occurred. Before deciding whether someone should take aspirin to prevent a stroke caused by a blockage in an artery (ischemic stroke), your doctor must consider whether you are at an increased risk of strokes caused by bleeding in the brain (hemorrhagic stroke), as well as bleeding elsewhere in the body.

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that people who have heart disease should take daily low-dose aspirin (81 mg a day), if told to by their doctor, for primary prevention of stroke or heart attack. Aspirin therapy may also be recommended as primary prevention for certain patients at increased risk for heart disease (for example, people with diabetes who smoke). New guidelines on stroke prevention in women recommend low-dose aspirin therapy for people with pregnancy-related hypertension (preeclampsia).

For these people, the benefits of aspirin outweigh its risks, which include bleeding in the stomach and brain. Healthy people who do not have heart disease, or a history of heart attack or stroke, should not take daily aspirin.

Secondary Prevention (to prevent another stroke after one has occurred)

After an ischemic stroke or a TIA, aspirin alone or aspirin plus the antiplatelet drug dipyridamole (Persantine, or Aggrenox when combined in one pill with aspirin) given twice daily is recommended to prevent another stroke.

Clopidogrel (Plavix, generic) may be used in place of aspirin for patients who have narrowing of the coronary arteries or who have had a stent inserted. Combining aspirin and clopidogrel together does not have any more benefit and increases the risk for hemorrhage (although some people who have had a coronary artery stent placed may need to be on this combination to keep their stents open).

Anticoagulant Medications for Preventing Stroke

Anticoagulants are also referred to as anti-clotting or "blood thinner" drugs. They are used to help prevent blood clots and stroke. They are generally considered the best medications for stroke prevention for most patients with atrial fibrillation who are at medium to high risk for stroke.

Anticoagulants may also be recommended for those with rheumatic heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, prosthetic or man-made heart valve, and a blood clot that remains in the left ventricle (ventricular thrombus).

Warfarin

Warfarin (Coumadin, generic) has been the main anticoagulant ("blood thinner") drug used to prevent strokes in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. Like all anticoagulants, warfarin carries a risk for bleeding. But for most people, its benefits far outweigh its risks. The risk for bleeding is highest when warfarin therapy is first started, with higher doses, and with long periods of treatment. People at risk for bleeding are usually older (over 65) and have a history of stomach bleeding, uncontrolled high blood pressure, alcohol abuse, or abnormal liver or kidney function.

It is important that patients who take warfarin have their blood checked regularly to make sure that it does not become "too thin." Blood that is too thin increases the risk for bleeding, while blood that is "too thick" increases the risk for blood clots and stroke. Prothrombin time (PT) and international normalized ratio (INR) tests are used to monitor blood coagulation.

People who take warfarin need to be careful about the amount of vitamin K they consume from foods in their diet. Too much vitamin K can weaken warfarin's effectiveness. Foods and beverages that are rich in vitamin K include kale, spinach, collard greens, mustard greens, chard, parsley, and green tea. Also, cranberry juice and alcohol can increase the effects of warfarin and the risks for bleeding. Talk with your doctor about any changes to your diet that you may need to make.

Alternatives to Warfarin

In recent years, several new anticoagulants have been approved as alternatives to warfarin for preventing stroke and blood clots in people with atrial fibrillation that is not caused by a heart valve problem. These newer anticoagulants are dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and apixaban (Eliquis). The FDA warns that these new anticoagulants should not be used by people who have mechanical heart valves. (Warfarin is recommended for treating atrial fibrillation in people who have mechanical heart valves.)

Unlike warfarin, these drugs do not require regular blood test monitoring. However, dabigatran and rivaroxaban need to be taken twice-daily (warfarin and apixaban are taken once a day). Dabigatran appears to cause more gastrointestinal problems (indigestion, upset stomach, abdominal pain) than the other anticoagulants. Compared to warfarin, dabigatran also has a higher risk for gastrointestinal bleeding. But it has a lower risk for bleeding in the brain and clot-related strokes. There are some other differences between the various medications including that some must be used with caution in patients with kidney problems.

All anticoagulant drugs increase the risk for bleeding. A concern with the newer anticoagulants is that if bleeding does occur, the drug effect is irreversible. In contrast, vitamin K or the administration of fresh frozen plasma (a donated blood product) can rapidly reverse the anticoagulant effect of warfarin.

Left atrial appendage closure

The Watchman device is implanted into the heart of some patients with atrial fibrillation. It closes off part of the heart chamber where clots most likely form. This is a better choice for some patients who are at high risk for blood thinners.

Control Diabetes

People with diabetes should aim for good blood glucose level control with a goal of hemoglobin A1c levels of around 7%. Blood pressure goals for people with diabetes should generally be 130/80 mm Hg or less.

Control Blood Pressure

High blood pressure (hypertension) increases the risk for stroke. A normal blood pressure is below 120/80. High blood pressure is above 130/90. Reducing high blood pressure is essential in stroke prevention. In general, most patients with hypertension should aim for blood pressure below 130/90 mm Hg.

Drug therapy is recommended for people with hypertension who cannot control their blood pressure through diet and other lifestyle changes. Many different types of drugs are used to control blood pressure. They include diuretics, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor blockers, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers.

Hypertension is a disorder characterized by chronically high blood pressure. It must be monitored, treated, and controlled by medication, lifestyle changes, or a combination of both.

Lower LDL Cholesterol

For people with TIA or ischemic stroke due to atherosclerosis, high-intensity step therapy is recommended, regardless of baseline total LDL cholesterol level. Statin brands include lovastatin (Mevacor, generic), pravastatin (Pravachol, generic), simvastatin (Zocor, generic), fluvastatin (Lescol), atorvastatin (Lipitor, generic), rosuvastatin (Crestor), and pitavastatin (Livalo).

Surgery

The 2 main surgical procedures for stroke prevention are carotid endarterectomy (CAE) and carotid angioplasty with stenting (CAS).

Current guidelines from the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association recommend considering a patient's age when choosing between these procedures:

- For people more than age 70, carotid endarterectomy appears to have better outcomes than carotid angioplasty with stenting.

- For younger people, both procedures have similar risks for post-operative complications and long-term risk of future stroke.

There are also other reasons to choose one procedure over the other. These reasons include surgical risk factors and anatomic considerations (where the blockages are located).

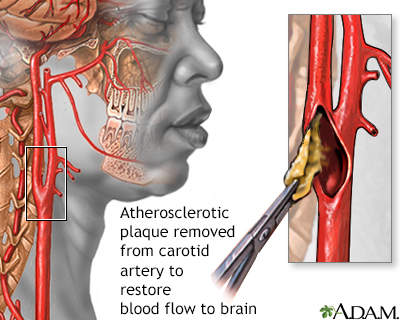

Carotid Endarterectomy

Carotid endarterectomy is a surgical procedure that cleans out plaque and opens up the narrowed carotid arteries in the neck. It is recommended to prevent ischemic stroke in some patients who have symptoms of carotid artery stenosis and carotid narrowing of 70% to 99%.

For people whose carotid arteries are narrowed by 50% or less, antiplatelet medications are usually recommended in place of surgery. For patients with moderate stenosis (50% to 69%), the decision to perform surgery needs to be determined on an individual basis.

There is a risk of a heart attack or stroke from the procedure. Anyone undergoing this procedure should be sure their surgeon is experienced in performing this procedure and that the medical center has complication rates of less than 6%. Carotid endarterectomy is generally not recommended for patients with acute stroke.

Procedure Description

A carotid endarterectomy involves:

- The person is usually given general anesthesia, although a local anesthetic is sometimes used.

- The surgeon cuts open the carotid artery and scrapes away the plaque on the arterial wall.

- The artery is sewn back together, and blood flow is restored.

- The person generally stays in the hospital for about 1 to 2 days.

- There is often a slight aching in the neck for about 2 weeks, and the person should refrain as much as possible from turning the head during this period. People may temporarily lose sensation in the neck area. It will go away within a few months.

Endarterectomy is a surgical procedure that removes plaque material from the lining of an artery.

Carotid Angioplasty and Stenting

Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) may be used as an alternative to carotid endarterectomy for some people. It is based on the same principles as angiography done for heart disease.

- A thin catheter tube is inserted into an artery in the groin.

- It is threaded through the circulatory system until it reaches the blocked area in the carotid artery.

- The doctor either breaks up the clot or inflates a tiny balloon against the blood vessel walls (angioplasty).

- After temporarily inflating the balloon, the doctor typically leaves a circular wire mesh (stent) inside the vessel to keep it open.

This procedure carries a risk for an embolic stroke and other complications. It is often used in hospitals as an alternative procedure for people who cannot undergo endarterectomy, especially for people with severe stenosis (blockage greater than 70%) and high surgical risk.

Vertebral Artery Angioplasty and Stenting

Similar procedures to those done to treat carotid artery narrowing have been studied for the vertebral arteries. However, vertebral artery angioplasty and stenting carry a lot more risk of bad outcomes during and after the surgery. As a result, medical treatment only is recommended for symptoms or findings in the vertebral artery system.

Brain Aneurysm Repair

If unruptured aneurysms are discovered in time, they can be treated before causing problems. People who are known to have an aneurysm may need regular doctor visits to make sure the aneurysm is not changing size or shape.

Treating high blood pressure may reduce the chance that an existing aneurysm will rupture. Controlling risk factors for atherosclerosis may reduce the likelihood of aneurysms from expanding or rupturing.

The decision to repair an unruptured cerebral aneurysm is based on the size and location of the aneurysm, and the patient's age and general health.

- Even if there are no symptoms, your doctor may order treatment to prevent a future, and possibly fatal, rupture.

- But not all aneurysms need to be treated right away. Those that are very small (less than 3 mm) are less likely to break open.

- Your doctor will help you decide whether or not it is safer to have surgery to block off the aneurysm before it can break open (rupture). Sometimes, people are too ill to have surgery, or it may be too dangerous to treat the aneurysm because of its location.

Two common methods are used to repair an aneurysm:

- Clipping is done during open brain surgery (craniotomy).

- Endovascular repair is most often done. It usually involves a coil or coiling. This is a less invasive way to treat some aneurysms.

During aneurysm clipping:

- You are given general anesthesia and a breathing tube.

- Your scalp, skull, and the coverings of the brain are opened.

- A metal clip is placed at the base (neck) of the aneurysm to prevent it from breaking open (bursting).

During endovascular repair of an aneurysm:

- You may have general anesthesia and a breathing tube. Or, you may be given medicine to relax you, but not enough to put you to sleep.

- A catheter is guided through a small cut in your groin to an artery and then to the blood vessel in your brain where the aneurysm is located.

- Contrast material is injected through the catheter. This allows the surgeon to view the arteries and the aneurysm on a monitor in the operating room.

- Thin metal wires are put into the aneurysm. They then coil into a mesh ball. For this reason, the procedure is also called coiling. Blood clots that form around this coil prevent the aneurysm from breaking open and bleeding. Sometimes stents (mesh tubes) are also put in to hold the coils in place.

- During and right after the procedure, you may be given heparin. This medicine prevents dangerous blood clots from forming.

Rehabilitation

Most people who survive a stroke will have some type of disability. But many people are able to make significant improvements through rehabilitation. According to the National Stroke Association:

- 10% of stroke survivors recover almost completely

- 25% recover with minor impairments

- 40% experience moderate-to-severe impairments that require special care

- 10% require care in a nursing home or other long-term facility

For the best chance of improvement and regaining abilities, it is important that rehabilitation starts as soon as possible after a stroke. Rehabilitation therapy is started in the hospital as soon as a person's condition has stabilized. Initial range of motion exercises involve a nurse or physical therapist moving a patient's affected limb (passive exercise) and having the patient practice moving the limb (active exercise). People are encouraged to gradually sit, stand, and walk, and then perform tasks of daily living (such as bathing, dressing, and using the toilet).

Some people will experience quick recovery and regain functional abilities in the first few days, while others will continue to show improvement during the first 6 months or longer. Recovery is an ongoing process and with good rehabilitation providers and family support, people can continue to make progress.

Rehabilitation Services

Once a person has been discharged from the hospital, rehabilitation continues at home or in an outpatient program. Some people may be transferred to a rehabilitation hospital before going home. Others may require care in a long-term or skilled nursing facility. In addition to the ongoing care of a primary care physician or neurologist, a rehabilitation team may include:

- Physical therapists who focus on restoring physical function and helping patients improve strength, balance, and coordination

- Occupational therapists to help patients regain the ability to perform activities of daily living

- Speech-language therapists to help improve language skills

- Psychologists to help with the patient's mental and emotional state

- Social workers to help patients and families with financial arrangements and coordinating home services

Effects of Stroke

A stroke can cause various disabilities. The type of disability depends on which part of the brain was damaged. According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the five main types of stroke disabilities are:

- Paralysis or Problems Controlling Movement (Motor Control). Paralysis tends to occur on the opposite side of the body from the side of the brain damage. If someone has brain damage on the left side of the brain, the right side of the body will be affected, and the reverse is also true. One-sided paralysis is called hemiplegia, and one-sided weakness is called hemiparesis. Hemiplegia or hemiparesis can affect a person's ability to walk or grasp objects. Loss of muscle control can also cause problems swallowing (dysphagia) or speaking (dysarthria). People may also have difficulty with coordination and balance (ataxia).

- Sensory Disturbances Including Pain. Stroke can affect the ability to feel touch, pain, temperature, or position. Pain, numbness, and tingling or pricking sensations can occur in the paralyzed or weakened limb (paresthesia). Sometimes patients have problems recognizing their affected arm or leg. Some stroke survivors experience chronic pain, which often results from a joint becoming immobilized or "frozen." Muscle stiffness or spasms are common. Sensory disturbances can also affect the ability to urinate or control bowels.

- Problems Using or Understanding Language (Aphasia). Many stroke survivors have language impairments, which affect the ability to speak, write, and understand spoken or written language. This condition is called aphasia. Sometimes people will know the right words but have problems saying them (dysarthria).

- Problems with Thinking and Memory. Stroke can affect attention span and short-term memory. This can impair the ability to make plans, learn new tasks, follow instructions, or comprehend meaning. Some stroke survivors are unable to recognize or understand their physical impairments or are unaware of sensations affecting the stroke-impaired side of the body.

- Emotional Disturbances. Some emotional and personality changes that follow a stroke are caused by the effects of brain damage. Clinical depression is very common, and is not only a psychological response to stroke but a symptom of physical changes in the brain. People may have difficulty controlling emotions or may exhibit inappropriate emotional responses (crying, laughing, or smiling for no apparent reason).

Rehabilitation Programs

Because stroke affects different parts of the brain, specific approaches to managing rehabilitation vary widely among individual people:

- Exercise program. Guidelines from the Veteran's Administration recommend that patients get back on their feet as soon as possible to prevent deep vein thrombosis. People should try to walk at least 50 feet a day. Assisted devices or bracing are sometimes used to help support the legs. Treadmill exercises can be very helpful for people with mild-to-moderate dysfunction. Exercise should be tailored to the stroke survivor's physical condition and can include aerobic, strength, flexibility, and neuromuscular (coordination and balance) activities.

- Retraining muscles. Stretching and range-of-motion exercises are used to help treat spastic muscles. They can also help patients regain function in a paralyzed arm. Multiple techniques have been developed and studied.

- Speech therapy and sign language. Intense speech therapy after a stroke is important for recovery. Some doctors recommend 9 hours a week of therapy for 3 months. Language skills improve the most when family and friends help reinforce the speech therapy lessons.

- Swallowing training. Training people and their caregivers regarding swallowing techniques, as well as safe and not-safe foods and liquids, is essential for preventing aspiration (accidental sucking in of food or fluids into the airway).

- Attention training. Problems with attention are very common after strokes. Direct retraining teaches people to perform specific tasks using repetitive drills in response to certain stimuli. (For example, they are told to press a buzzer each time they hear a specific number.) A variant of this approach trains patients to relearn real-life skills, such as driving, carrying on a conversation, or other daily tasks.

- Occupational training. Occupational therapy is important and improves daily living activities and social participation.

Drug Therapy for Rehabilitation

Medication can sometimes help relieve specific effects of stroke:

- Dantrolene (Dantrium, generic), tizanidine (Zanaflex, generic), and baclofen (Lioresal, Gablofen, generic) are used to treat spasticity. Botox injections are approved for treatment of upper limb spasticity (such as the elbow, wrist, or fingers).

- Heparin, a blood-thinning drug, is used to prevent blood clots from forming in the veins of the legs (thrombosis).

- Some people experience constant hiccups, which can be very serious. Chlorpromazine and baclofen are among the drugs used for this condition.

- Antidepressants may be prescribed for treatment of depression.

Managing the Emotional Consequences

A stroke is emotionally challenging both for patients and their families. The caregiver's emotions and responses to the patient are critical. People do worse when caregivers are depressed, overprotective, or not knowledgeable about the stroke. They do best when caregivers and family are encouraging and supportive. Everyone benefits when people are able to function as independently as possible to the best of their abilities.

Resources

- American Stroke Association -- www.strokeassociation.org

- American Heart Association -- www.heart.org

- National Stroke Association -- www.stroke.org

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke -- www.ninds.nih.gov

- National Aphasia Association -- www.aphasia.org

- American Academy of Neurology -- www.aan.com

References

Berkhemer OA, Fransen PS, Beumer D, et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:11-20. PMID: 25517348 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25517348/.

Biller J, Schneck MJ, Ruland S. Ischemic cerebrovascular disease. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 65.

Brott TG, Howard G, Roubin GS, et al. Long-term results of stenting versus endarterectomy for carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1021-1031. PMID: 26890472 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26890472/.

Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1545-1588. PMID: 24503673 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24503673/.

Campbell BCV, De Silva DA, Macleod MR, Coutts SB, Schwamm LH, Davis SM, Donnan GA. Ischaemic stroke. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):70. PMID: 31601801 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31601801/.

Campbell BCV, Khatri P. Stroke. Lancet. 2020;396(10244):129-142. PMID: 32653056 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32653056/.

Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935-2959. PMID: 24239921 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239921/.

Goldstein LB. Prevention and management of ischemic stroke. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann, DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 65.

January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(21):e1-e76. PMID: 24685669 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24685669/.

Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236. PMID: 24788967 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24788967/.

Lee YM, Magarik JA, Mocco J. Acute medical management of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 360.

Magarik JA, Lee YM, Mocco J. Endovascular management of intracranial occlusion disease. In: Winn HR, ed. Youmans and Winn Neurological Surgery. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017:chap 372.

Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B, et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3754-3832. PMID: 25355838 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25355838/.

Oza R, Rundell K, Garcellano M. Recurrent ischemic stroke: strategies for prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(7):436-440. PMID: 29094912 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29094912/.

Poorthuis MH, Algra AM, Algra A, Kappelle LJ, Klijn CJ. Female- and male-specific risk factors for stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):75-81. PMID: 27842176 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27842176/.

Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. PMID: 29367334 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29367334/.

Prabhakaran S, Ruff I, Bernstein RA. Acute stroke intervention: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313(14):1451-1462. PMID: 25871671 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25871671/.

Rosenfield K, Matsumura JS, Chaturvedi S, et al. Randomized trial of stent versus surgery for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(11):1011-1020. PMID: 26886419 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26886419/.

Saunders DH, Greig CA, Mead GE. Physical activity and exercise after stroke: review of multiple meaningful benefits. Stroke. 2014;45(12):3742-3747 PMID: 25370588 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25370588/.

Schellinger PD, Demaerschalk BM. Endovascular stroke therapy in the late time window. Stroke. 2018;49(10):2559-2561. PMID: 30355126 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30355126/.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127-e248. PMID: 29146535 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29146535/.

Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(6):e98-e169. PMID: 27145936 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27145936/.

Yaghi S, Willey JZ, Cucchiara B, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Treatment and outcome of hemorrhagic transformation after intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2017;48(12):e343-e361. PMID: 29097489 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29097489/.

Zhong CS, Beharry J, Salazar D, et al. Routine use of Tenecteplase for thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2021;52(3):1087-1090. PMID: 33588597 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33588597/.

|

Review Date:

3/29/2021 Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.