Diabetes diet - InDepth

Highlights

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) guideline for nutrition therapy recommends:

- Eat a variety of healthy foods in appropriate portion sizes.

- Choose an eating plan (Mediterranean diet, DASH diet, vegetarian, or low-carb) that works best for your personal food preferences and lifestyle. There's no evidence that one plan works better than another. Find one that appeals to you, makes sense to you, and you believe you can afford and maintain over time.

- The ADA no longer recommends specific amounts for carbohydrate, fat, or protein intake. But they do suggest that people get their carbs from vegetables, whole grains, fruits, and legumes. Avoid carbs high in fat, sodium, and sugar.

- People with prediabetes or diabetes should consult a registered dietitian (RD) who is knowledgeable about diabetes nutrition. An experienced dietician can provide valuable advice and help create an individualized diet plan. Some RDs are certified diabetes educators.

- Moderate weight loss may postpone or prevent the transition from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes cannot be reversed, but weight loss and physical activity can both help with management. Physical activity is also important for people with type 1 diabetes.

- Carbohydrate counting is important for people with type 1 diabetes or anyone taking insulin. The glycemic index, which measures how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food raises blood sugar levels, may be a helpful addition to carbohydrate counting for some people.

Introduction

The two major forms of diabetes are type 1, previously called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) or juvenile-onset diabetes, and type 2, previously called non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) or adult-onset diabetes. There are other forms of diabetes that account for about 1 out of every 20 people with diabetes.

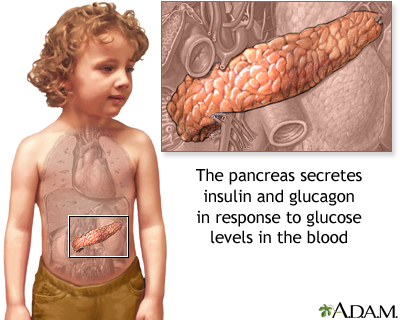

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes share one central feature: elevated blood sugar (glucose) levels due to a deficiency of or resistance to insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. Insulin is a key regulator of the body's metabolism. It normally works in the following way:

- The main components (macronutrients) of food are fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are primarily what affect blood glucose levels. During and immediately after a meal, digestion breaks carbohydrates down into sugar molecules (of which glucose is one) and proteins into amino acids.

- Right after the meal, glucose and amino acids are absorbed directly into the bloodstream, and blood glucose levels rise sharply. (Glucose levels after a meal are called postprandial levels.)

- The rise in blood glucose levels signals important cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, to secrete insulin, which pours into the bloodstream. Within 10 minutes after a meal, insulin rises to its peak level.

- Insulin then enables glucose to enter cells in the body, particularly muscle and fat cells. Here, insulin and other hormones direct whether glucose will be burned for energy or stored for future use. Insulin is also important in telling the liver how to process glucose.

- When insulin levels are high, the liver stops producing glucose and stores it in other forms until the body needs it again.

- As blood glucose levels reach their peak, the pancreas reduces the production of insulin.

- About 2 to 4 hours after a meal both blood glucose and insulin are at normal levels, with insulin being slightly higher than before the meal. When talking with your provider the blood glucose levels before another meal (e.g., after breakfast but just before lunch) are then referred to as preprandial blood glucose concentrations. The term fasting blood glucose usually refers only to the blood sugar early in the morning before breakfast when you have not eaten all night or for at least 8 hours.

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce insulin. Onset is usually in childhood or adolescence, but can occur in adults. Type 1 diabetes is considered an autoimmune disorder meaning your own immune system is involved in causing the disease.

People with type 1 diabetes need to take insulin. Dietary control in type 1 diabetes is very important and focuses on balancing food intake with insulin intake and energy expenditure from physical exertion. Only about 5% of people with diabetes have type 1 diabetes.

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, accounting for about 90% of people with diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, the body does not respond normally to insulin, a condition known as insulin resistance, which means your body needs to make more insulin to achieve the same control over blood sugar levels. Over time, your ability to make high levels of insulin decreases and then type 2 diabetes develops. In type 2 diabetes, the initial effect is usually an abnormal rise in blood sugar right after a meal (called impaired glucose tolerance OR postprandial hyperglycemia).

People whose blood glucose levels are higher than normal, but not yet high enough to be classified as diabetes, are considered to have prediabetes (also called impaired fasting glucose). It is very important that people with prediabetes control their weight to stop or delay the progression to diabetes.

Obesity is common in people with type 2 diabetes, and this condition appears to be related to insulin resistance. The primary dietary goal for overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes is weight loss and maintenance. With regular physical activity and diet modification programs, many people with type 2 diabetes can minimize or even avoid medications. Weight loss medications or bariatric surgery may be appropriate for some people. Most people only need to lose 5% to 10% body weight to cause a big improvement in control of their blood sugar level.

General Dietary Guidelines

Lifestyle changes of diet and exercise are extremely important for people who have prediabetes, or who are at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Lifestyle interventions can be very effective in preventing or postponing the progression to diabetes. These interventions are particularly important for overweight or obese people. Even moderate weight loss can help reduce diabetes risk.

The American Diabetes Association recommends that people at high risk for type 2 diabetes lose weight (if necessary), engage in regular physical exercise, and follow a diet with reduced calories and lower dietary fat. High-fiber (14 grams fiber for every 1,000 calories) and whole-grain foods are recommended for prevention. These strategies can help reduce type 2 diabetes risk.

People who are diagnosed with diabetes need to be aware of their heart health nutrition and, in particular, controlling high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

For people who have diabetes, the treatment goals for diabetes diet are:

- Achieve near normal blood glucose levels. People with type 1 diabetes and people with type 2 diabetes who are taking insulin or oral medication (particularly sulfonylureas) must coordinate calorie intake with medication or insulin administration, exercise, and other variables to control blood glucose levels while avoiding low blood sugar.

- Protect the heart and aim for healthy lipid (cholesterol and triglyceride) levels and control of blood pressure.

- Achieve and maintain reasonable weight. Overweight and obese people with type 2 diabetes should aim for a diet that controls both weight and glucose. A reasonable weight is usually defined as what is achievable and sustainable, and helps attain normal blood glucose levels. The goal for a healthy weight is a BMI <25. Children, pregnant women, and people recovering from illness should be sure to maintain adequate calories for health.

- Delay or prevent complications of diabetes.

The American Diabetes Association's nutritional guidelines recommend:

- The American Diabetes Association no longer advises a uniform ideal percentage of daily calories for carbohydrates, fats, or protein for all people with diabetes. Rather, these amounts should be individualized, based on your unique health profile.

- Choose carbohydrates that come from vegetables, whole grains, fruits, beans (legumes), and dairy products. Avoid carbohydrates that contain excess added fats, sugar, or sodium.

- Choose "good" fats over "bad" ones. The type of fat may be more important than the quantity. Monounsaturated (olive, peanut, and canola oils; avocados; and nuts) and omega-3 polyunsaturated (fish, flaxseed oil, and walnuts) fats are the best types of fats. Avoid unhealthy saturated fats (red meat and other animal proteins, butter, lard) and trans fats (hydrogenated fat found in snack foods, fried foods, commercially baked goods).

- Choose protein sources that are low in saturated fat. Fish, poultry, legumes, and soy are better protein choices than red meat. Prepare these foods with healthier cooking methods that do not add excess fat: Bake, broil, steam, or grill instead of frying. If frying, use healthy oils like olive or canola oil.

- Try to eat fatty fish, which are high in the omega-3 fatty acids DHA and EPA, at least twice a week. Salmon, herring, trout, and sardines are some of the best sources of DHA; sardines typically contain the highest amount.

- Limit intake of sugar-sweetened beverages including those that contain high fructose corn syrup or sucrose (soda, juice, sports drinks). They are bad for your waistline and your heart.

- Sodium (salt) intake should be limited to 2,300 mg/day or less. People with diabetes and high blood pressure may need to restrict sodium even further. Reducing sodium can lower blood pressure, protect the kidneys, and decrease the risk of heart disease and heart failure.

There is no such thing as a single diabetes diet. People should meet with a professional dietitian to plan an individualized diet within the general guidelines that takes into consideration their own health needs.

For example, a person with type 2 diabetes who is overweight and insulin resistant may need to have a different carbohydrate-protein balance than a thin person with type 1 diabetes in danger of kidney disease. Because regulating diabetes is an individual situation, everyone with this condition should get help from a dietary professional in selecting their best diet.

Recommended eating plans include Mediterranean, vegetarian, and lower-carbohydrate diets. (Vegetarian diets can be tricky to balance because vegetarian protein sources contain carbohydrates while animal protein sources do not.) However, there is no evidence that one plan is better than another.

What is most important is to find a healthy eating plan that works best for you and your lifestyle and food preferences. Whatever diet plan you follow, try to eat a variety of nutrient-rich food in appropriate portion sizes.

Several different dietary methods are available for controlling blood sugar in type 1 and insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes:

- Diabetic exchange lists (for maintaining a proper balance of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins throughout the day)

- Carbohydrate counting (for tracking the number of grams of carbohydrates consumed each day) is important for people with type 1 diabetes

- Glycemic index (for tracking which carbohydrate foods increase blood sugar the most)

Tests for Glucose Levels

Both low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) are of concern for people who take insulin. It is important, therefore, to monitor blood glucose levels carefully as instructed by your provider. Depending on your type of diabetes and the medications you take you may be asked to measure your blood sugar from 0 to 7 times a day. In some cases, a continuous glucose monitor may be recommended.

In general, most adult people should aim for the following measurements goals (people with gestational diabetes may have different goals):

- Premeal (preprandial) glucose levels of 80 to 130 mg/dL

- Postmeal (postprandial) glucose levels of less than 180 mg/dL

Hemoglobin A1C Test

Hemoglobin A1C (also called HbA1c or HA1c) is measured periodically up to every 3 months, or at least twice a year, to determine the average blood-sugar level over the lifespan of the red blood cell. While point of care (fingerstick) self-testing provides information on blood glucose for that moment, the A1C test shows how well blood sugar has been controlled over a period of several months. A1C goals should be individualized, but for most adults with well-controlled diabetes, A1C level goals should be less than 7%. For children, A1C should be less than 7.5%. (For people who do not have diabetes, normal A1C is <6%.)

Other Tests

Other tests are needed periodically to screen for potential complications of diabetes, such as high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and kidney problems. Such tests may also indicate whether current diet plans are helping the person and whether changes should be made. Periodic urine tests for albumin and blood tests for creatinine can indicate a future risk for serious kidney disease.

Food Labels

Every year thousands of new packaged foods are introduced, many of them advertised as nutritionally beneficial. It is important for everyone, mostly people with diabetes, to be able to differentiate advertised claims from truth.

In 2014, the FDA announced that it would be revising food labels to better reflect new dietary requirements, and highlight key information such as calories and serving sizes. The proposed labels will include information on fats, cholesterol, protein, sodium, total carbs, and dietary fiber. A new feature will be the distinction of sugars and "added sugars" to help consumers better understand how much sugar is naturally in the product, and how much has been added. Potassium and vitamin D information will also be required.

Labels show "daily values," the percentage of a daily diet that each of the important nutrients offers in a single serving. This daily value is based on 2,000 calories, which is often higher than what most people with diabetes should have. The serving size on a food label often does not match the serving size of the diabetic exchange lists. For a person who is carbohydrate counting, a serving size contains 15 grams of carbohydrate. When calculating the serving size information, use only "total carbohydrate"; do not adjust to the diabetic exchange list using sugar or added sugar.

Weighing and Measuring

Weighing and measuring food is extremely important to get the correct number of daily calories.

- Along with measuring cups and spoons, choose a food scale that measures grams. (A gram is about 1/28th of an ounce.)

- Food should be weighed and measured after cooking.

- After measuring all foods for a week or so, most people can make fairly accurate estimates by eye or by holding food without having to measure everything every time they eat.

Timing

People with diabetes should not skip meals, particularly if they are taking insulin. Skipping meals can upset the balance between food intake and insulin and also can lead to low blood sugar and even weight gain if the person eats extra food to offset hunger and low blood sugar levels.

The timing of meals is particularly important for people taking insulin:

- People should coordinate insulin administration with calorie intake. In general, they should eat 3 meals each day at regular intervals. Snacks are sometimes necessary in people with type 1 diabetes.

- Some health care providers recommend a fast acting insulin (rapid acting analog) before each meal and a longer (basal) insulin once a day, often at night.

- Be sure to check blood sugar before, and sometimes after, meals and snacks as directed by your provider.

Major Food Components

Compared to fats and protein, carbohydrates have the greatest impact on blood sugar (glucose). There are three main types of carbohydrates: sugars, starches, and fiber. Dietary fiber is not digestible. Sugars and starches are eventually broken down by the body into glucose.

Starches

Starches are broken down more slowly by the body than sugars. Some foods that are high in starch content are more likely to provide other nutritional components, as well as fiber:

- Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, beans, and dairy products are good sources of carbohydrates.

- Whole grain foods such as brown rice, quinoa, bulgur, farro, oatmeal, and whole-wheat bread (when you can see the seeds and whole grains), provide more nutritional value than pasta, white rice, white bread, and white potatoes.

Fiber

Fiber is an important component of many plant-based foods. There are two types of fiber:

- Soluble fiber attracts water and turns to gel during digestion. This slows digestion. Soluble fiber is found in oat bran, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, peas, and some fruits and vegetables. It is also found in psyllium, a common fiber supplement. Some types of soluble fiber may help lower cholesterol, but the effect on heart disease is not known.

- Insoluble fiber is found in foods such as wheat bran, vegetables, and whole grains. It adds bulk to the stool and appears to help food pass more quickly through the intestines.

Sugars

Sugars add calories, increase blood glucose levels quickly, and provide little or no other nutrients:

- Sucrose (table sugar) is the source of most dietary sugar, found in sugar cane, honey, and corn syrup.

- Fructose, the sugar found in fruits, produces a smaller increase in blood sugar than sucrose. The modest amounts of fructose in fruit can be handled by the liver without significantly increasing blood sugar, but the large amounts in soda and other processed foods with high-fructose corn syrup overwhelm normal liver mechanisms and trigger production of unhealthy triglyceride fats.

- A third sugar, lactose, is a naturally occurring sugar found in dairy products including yogurt and cheese.

People with diabetes should avoid products listing more than 5 grams of sugar per serving, and some providers recommend limiting fruit intake. Although moderation is important, fruits are an important part of any diet. They provide essential vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, as well as fiber. You can limit your fructose intake by consuming fruits that are relatively lower in fructose (cantaloupe, grapefruit, strawberries, peaches, bananas) and avoiding added sugars such as those in sugar-sweetened beverages. Fructose is metabolized differently than other sugars and can significantly raise triglycerides, though usually a large intake of fructose is needed to do this (or drinking fructose sweetened beverages with a meal).

In addition, limit processed foods with added sugars of any kind. Pay attention to ingredients in food labels that indicate the presence of added sugars. These include terms such as sweeteners, syrups, fruit juice concentrates, molasses, and sugar molecules ending in "ose" (like dextrose and sucrose).

Artificial sweeteners use chemicals that mimic the sweetness of sugar. They include aspartame (NutraSweet, Equal), sucralose (Splenda), saccharin (Sweet'N Low), and rebiana (Truvia). (Rebiana is an extract derived from the plant stevia.) These products do not contain calories and do not affect blood sugar. Artificial sweeteners can help with weight control, but it is important not to consume extra calories elsewhere. Artificial sweeteners have become more controversial in the past few years. Consumption of some artificial sweeteners is even associated with weight gain.

The Carbohydrate Counting System

Some people plan their carbohydrate intake using a system called carbohydrate counting. It is based on these premises:

- All carbohydrates (either from sugars or starches) will raise blood sugar to a similar degree based on the weight, although the rate at which blood sugar rises depends on the type of carbohydrate and on the individual. A higher peak won't last as long while a lower peak may take longer to return to premeal blood sugar levels, but the total area under the curve for the increase in blood sugar will be similar.

- Carbohydrates have the greatest impact on blood sugar. Fats and protein play only minor roles.

- Carbohydrate counting is very important for people with type 1 diabetes and anyone on an insulin regimen. Carbohydrate counting can even help control blood glucose levels in people with type 2 diabetes who are not on insulin regimens.

The basic goal of carbohydrate counting is to balance insulin with the amount of carbohydrates eaten in order to control blood sugar (glucose) levels after a meal. There are several options for counting carbohydrates. It's best to work with an RD.

A dietitian can create a meal plan that accommodates the person's weight and needs. Many people with type 1 diabetes work with their providers to determine a carbohydrate to insulin ratio. This special calculation tells the person how much insulin they need to take to cover a certain amount of carbohydrate in the meal. A common ratio would be 1 unit of insulin for 15 grams of carbohydrate. Then if you choose a meal with 60 grams of carbohydrate you know you need 4 units of insulin to match the carbohydrates and prevent the meal from increasing your blood sugar level. When people learn how to count carbohydrates and adjust insulin doses to their meals, many find this system more flexible, more accurate in predicting blood sugar increases, and easier to plan meals than other systems.

The Glycemic Index

The glycemic index helps determine which carbohydrate-containing foods raise blood glucose levels more or less quickly after a meal. The index uses a set of numbers for specific foods that reflect greatest to least delay in producing an increase in blood sugar after a meal. The lower the index number, the better the impact on glucose levels. This system is artificial in that the number is calculated when eating only that food. The index for mashed potato is 72, but eating the same amount of mashed potato with gravy, green beans and grilled chicken breast would change the absorption time significantly. The index also does not account for variation in food preparation. The lower (good) glycemic index of brown rice can be increased (bad) just by increasing the cooking time. The index also does not account for mixed meals. For example, eating white rice with a sauce that includes chicken, vegetables and coconut milk will change the glycemic index vs. eating white rice alone.

There are two indices in use. One uses a scale of 1 to 100 with 100 representing a glucose tablet, which has the most rapid effect on blood sugar. [See Table: "The Glycemic Index of Some Foods," below.] The other common index uses a scale with 100 representing white bread (so some foods will be above 100).

Choosing foods with low glycemic index scores may have a modest effect on controlling the surge in blood sugar after meals. Substituting low- for high-glycemic index foods may also help with weight control.

One easy way to improve glycemic index is to simply replace starches and sugars with whole grains and legumes (dried peas, beans, and lentils). However, there are many factors that affect the glycemic index of foods, and maintaining a diet with low glycemic load is not straightforward.

No one should use the glycemic index as a complete dietary guide, since it does not provide nutritional guidelines for all foods. It is simply an indication of how the body will respond to certain carbohydrates.

Based on 100 = a Glucose Tablet | |

BREADS | |

Pumpernickel | 49 |

Sour dough | 54 |

Rye | 64 |

White | 69 |

Whole wheat | 72 |

GRAINS | |

Barley | 22 |

Sweet corn | 58 |

Brown rice | 66 |

White rice | 72 |

BEANS | |

Soy | 14 |

Red lentils | 27 |

Kidney (dried and boiled, not canned) | 29 |

Chickpeas | 36 |

Baked | 43 |

DAIRY PRODUCTS | |

Milk | 30 |

Ice cream | 60 |

CEREALS | |

Oatmeal | 53 |

All Bran | 54 |

Swiss Muesli | 60 |

Shredded Wheat | 70 |

Corn Flakes | 83 |

Puffed Rice | 90 |

PASTA | |

Spaghetti-protein enriched | 28 |

Spaghetti (boiled 5 minutes) | 33 |

Spaghetti (boiled 15 minutes) | 44 |

FRUIT | |

Strawberries | 32 |

Apple | 38 |

Orange | 43 |

Orange juice | 49 |

Banana | 61 |

POTATOES | |

Sweet | 50 |

Yams | 54 |

New | 58 |

Mashed | 72 |

Instant mashed | 86 |

White | 87 |

SNACKS | |

Potato chips | 56 |

Oatmeal cookies | 57 |

Corn chips | 72 |

SUGARS | |

Fructose | 22 |

Refined sugar | 64 |

Honey | 91 |

Note. These numbers are general values, but they may vary widely depending on other factors, including if and how they are cooked and foods they are combined with. | |

Low-Carbohydrate Diets

Low-carbohydrate diets generally restrict the amount of carbohydrates but do not restrict protein and fat sources. The larger variation usually becomes the fat content as the percent of calories from protein does not vary as much between diets:

- Low-carbohydrate diets are mostly fairly similar (such as Paleo, South Beach, Atkins, Sugar Busters.)

- While initial phases and instructions vary, the majority of the caloric reduction comes from eliminating the big starches (rice, bread, pasta, potato, flour).

- Although there have been concerns that these diets may be harmful for bone and kidney health, good scientific studies have not shown evidence of these effects.

- Many of these diets make other claims related to hunger, satiety, exercise tolerance, energy, and immune system function, but none of these claims have been proven by any scientific studies.

- All of these diets work by reducing the number of calories you are eating rather than through any of the many claims of special properties related to the diet itself or the supplements that you may be asked to purchase.

- These diets fail as soon as the diet is liberalized and people start adding low-carbohydrate cookies, chips, and bread back to their diet thereby increasing their caloric intake.

- The Mediterranean diet is a heart-healthy diet that is rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains as well as healthy monounsaturated fats such as olive oil. It restricts saturated fat proteins like red meat. Studies on the Mediterranean diet are difficult to interpret, as the definition of the diet itself may vary. However, in studies of people with type 2 diabetes, a low carbohydrate version of the diet (restricting carbohydrates to less than 50% of total calories) worked better than a low-fat diet in promoting weight loss, reducing A1C levels, and improving insulin sensitivity and glycemic control.

Protein is important for strong muscles and bones. Eating protein may help people feel full sooner and longer and thus reduces overall calories. In addition, protein consumption helps the body maintain lean body mass during weight loss. However, some types of protein (red meat, full-fat dairy products) are high in saturated fat, which can be bad for the heart and can make weight gain more likely.

Good sources of protein include fish, skinless chicken or turkey, low-fat dairy products, soy (tofu), and legumes (such as kidney beans, black beans, chickpeas, and lentils).

Plant Proteins

Legumes are one of the healthiest types of foods and are an important source of protein for vegetarians. Legumes include all sorts of beans such as black beans, pinto beans, lentils, and chickpeas. Dried beans can take more time to prepare, but they have less sodium (salt) than canned varieties. You can also reduce sodium by draining and rinsing canned products.

Soy protein is found in products such as tofu, soy milk, and soybeans. (Soy sauce is not a good source. It contains only a trace amount of soy and is very high in sodium.)

Plant-based proteins are rich in both soluble and insoluble fiber, and have more vitamins and minerals than meat or dairy proteins. They are also low in fat.

Fish

Fish is one of the best sources of protein. Evidence suggests that eating moderate amounts of fish (twice a week) may improve triglycerides and help lower the risks for death from heart disease. The healthiest fish are oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, or sardines, which are high in omega-3 fatty acids.

The omega-3 fatty acids contained in fish oil are also available as dietary supplements. However, according to the American Diabetes Association, there is no evidence that shows these supplements help prevent or treat diabetes. Eating fish is a better way to get omega-3 fatty acids.

Meat and Poultry

Lean cuts of meat are the best choice for heart health and diabetes control. Saturated fat in meat is the primary danger to the heart. The fat content of meat varies depending on the type and cut. Skinless chicken or turkey, which are lower in saturated fat, are better choices than red meat. (Fish is an even better choice.)

Dairy Products

A high intake of dairy products may lower risk factors related to type 2 diabetes and heart disease (insulin resistance, high blood pressure, obesity, and unhealthy cholesterol). Some research suggests the calcium in dairy products may be partially responsible for these benefits. Vitamin D contained in dairy may also play a role in improving insulin sensitivity, particularly for children and adolescents. However, because many dairy products are high in saturated fats and calories, it's best to choose low-fat and nonfat dairy items. Some nonfat items have a lot of added sugar - check the label!

Fats can have good or bad effects on health, depending on their chemistry. The type of fat appears to be more important than the total amount of fat when it comes to reducing heart disease, but all fats should be consumed in moderation. All fats, good or bad, are high in calories compared to proteins and carbohydrates. One fat gram provides 9 calories.

Current dietary guidelines for diabetes and heart health recommend that:

- Monounsaturated fatty acids (found in olive oil, canola oil, peanut oil, nuts, and avocados) and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (found in fish, shellfish, flaxseed, and walnuts) should be the first choice for fats.

- Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oils and nuts and seeds) are the second choice for fats.

- Limit saturated fat (found predominantly in animal products, including meat and full fat dairy products, as well as coconut and palm oils) to less than 7% of total daily calories.

- Avoid trans fats (found in margarine, commercial baked goods, snacks, and fried foods). Trans fats are listed on nutrition facts food labels. Even if 0 trans fats are listed, look at the list of ingredients for words like hydrogenated oil or partially hydrogenated oil. Avoid foods that have a liquid oil listed first on the ingredients list.

Try to replace saturated fats and trans fatty acids with unsaturated fats from plant and fish oils. Omega-3 fatty acids, which are found in fish and a few plant sources, are a good source of unsaturated fats. Fish oils contain the omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic (DHA) and eicosapentanoic (EPA) acids, which have significant benefits for the heart. Generally, 2 servings of fish per week provide a healthful amount of these omega-3 fatty acids.

Animal-based foods contain cholesterol, which contributes to heart disease. (However, saturated fat has a much greater impact on cholesterol levels than dietary cholesterol.) High amounts of cholesterol occur in meat, dairy products, and shellfish. Although egg yolks contain cholesterol, up to 2 eggs (whole eggs) per day can be healthful for most people and are a good source of protein, iron, and B vitamins.

Plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains, do not contain cholesterol. Plant substances known as sterols, and their derivatives called stanols, may reduce cholesterol by blocking its absorption in the intestinal tract. Margarines containing sterols are available.

Sodium (Salt)

It is important for everyone to restrict their sodium (salt) intake. People with diabetes should reduce sodium intake to no more than 2,300 mg daily (less than 1 teaspoon of salt). Some people may benefit from restricting sodium intake to no more than 1,500 mg per day. Limiting or avoiding consumption of processed foods can go a long way to reducing salt intake. Simply eliminating table and cooking salt is also beneficial. The DASH diet is an excellent heart-healthy eating plan that restricts sodium.

Salt substitutes, such as Nu-Salt and Mrs. Dash (which contain mixtures of potassium, sodium, and magnesium) are available, but they can be risky for people with kidney disease or those who take blood pressure medication that causes potassium retention.

Potassium

Potassium-rich foods are also important for good blood pressure. The best source of potassium is from the fruits and vegetables that contain them. Potassium-rich foods include bananas, oranges, pears, prunes, cantaloupes, tomatoes, dried peas and beans, nuts, potatoes, and avocados.

People with diabetes should check with their providers before increasing the amount of potassium in their diets. Eating too many potassium-rich foods can cause problems for some people. (No one should take potassium supplements without consulting a provider.) Kidney problems can cause potassium overload, and medications commonly used in diabetes (such as ACE inhibitors or potassium-sparing diuretics) also limit the kidney's ability to excrete potassium.

Alcohol

The American Diabetes Association recommends limiting alcoholic beverages to 1 drink per day for non-pregnant adult women and 2 drinks per day for adult men. Excess alcohol intake can increase the risk of both high (hyperglycemia) and low (hypoglycemia) blood sugar.

Coffee

Many studies have noted an association between coffee consumption (both caffeinated and decaffeinated) and reduced risk for developing type 2 diabetes. Researchers are still not certain if coffee protects against diabetes. (If you drink coffee, don't add sugar or creamers, which negate any possible benefits.)

Research has shown that vitamin supplements have no benefit for heart disease or diabetes. Because of the lack of scientific evidence for benefit, the American Diabetes Association does not recommend regular use of vitamin or mineral supplements, except for people who have nutritional deficiencies.

People with type 2 diabetes who take metformin (Glucophage, generic) should be aware that this drug can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption. Calcium supplements may help counteract metformin-associated vitamin B12 deficiency.

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. People should always check with their providers before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Traditional herbal remedies for diabetes include bitter melon, cinnamon, fenugreek, and Gymnema sylvestre. Few well-designed studies have examined these herbs' effects on blood sugar, and there is not enough evidence to recommend them for prevention or treatment of diabetes.

Various fraudulent products are often sold on the Internet as "cures" or treatments for diabetes. These dietary supplements have not been studied or approved. The FDA warns people with diabetes not to be duped by bogus and unproven remedies.

Weight Control for Type 2 Diabetes

The American Diabetes Association recommends that overweight and obese people aim for a small but consistent weight loss of ½ to 1 pound (0.2 to 0.5 kilogram) per week. For overweight and obese people with diabetes, high intensity short-term programs of dieting, physical exercise, and behavioral interventions are recommended initially for achieving at least 5% weight loss over 3 to 6 months. If this goal is achieved, long-term programs are then recommended for weight maintenance. A registered dietician can compute a daily calorie goal for you based on your height, weight, age, sex, and activity level. Some registered dieticians are also certified diabetes educators.

Even modest weight loss can reduce the risk of heart disease and diabetes. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), low-carbohydrate, low-fat calorie-restricted, or Mediterranean diets may help reduce weight in the short term (up to 2 years). Physical activity and behavior modification are also important for achieving and maintaining weight loss.

Here are some general weight loss suggestions that may be helpful:

- Start with realistic goals. When overweight people achieve even modest weight loss they reduce risk factors in the heart. Ideally, overweight people should strive for 7% weight loss or better, particularly people with type 2 diabetes.

- A regular exercise program (at least 150 minutes of moderate exercise per week) is essential for maintaining weight loss. Recommended goals are 90 minutes/day for weight loss, 60 minutes/day for maintenance, and 30 minutes/day for overall heart health and prevention of weight gain. The 150 minutes per week should be spread over at least 3 days and you should have no more than 2 consecutive days without exercising. Check with your provider before starting any exercise program.

- For people who cannot lose weight with diet alone, weight-loss medications may be considered.

- For severely obese people (a body mass index >40, or >35 with comorbidities), weight loss through bariatric surgery can help produce rapid weight loss, and improve insulin signaling and glucose levels in people with diabetes.

Calorie restriction has been the cornerstone of obesity treatment. Restricting calories in such cases also appears to have beneficial effects on cholesterol levels, including reducing LDL and triglycerides and increasing HDL levels.

The standard dietary recommendations for losing weight are:

- As a rough rule of thumb, 1 pound (0.5 kilogram) of fat contains about 3,500 calories, so one could theoretically lose a pound a week by reducing daily caloric intake by about 500 calories a day.

- Very low calorie diets are associated with better short-term success, but extreme diets can have some serious health consequences. A very low calorie "diet" is not going to be as effective in the long term as sustainable lifestyle modifications. Weight gain post diet is also more likely with extreme diets. The minus 500 kcal/day can come from increasing physical activity as well as reducing dietary intake.

- Fat intake should be no more than 30% of total calories. Most fats should be in the form of monounsaturated fats (such as olive oil). Avoid saturated fats (found in animal products).

Time-restricted eating means that you only allow yourself to eat for a certain number of hours a day. A 16:8 schedule would mean that you fast for 16 hours and can eat during only 8 hours (for example 10 am to 6 pm). Intermittent fasting usually involves not eating (no calorie-containing foods) for a full day or more (for example a 5:2 schedule would mean that you eat 5 days a week and fast the other two days). There are studies that show that these strategies can be successful for some people in losing weight and in improving blood sugar control. Talk to your provider and dietician if you are considering these diet strategies.

Aerobic exercise has significant and particular benefits for people with diabetes. Regular aerobic exercise, even of moderate intensity (such as brisk walking), improves insulin sensitivity. People with diabetes are at particular risk for heart disease, so the heart protective effects of aerobic physical activity are important. In addition to aerobic exercise, strength training is also helpful for blood sugar control and is recommended as part of any physical activity program for people with diabetes.

Exercise Precautions for People with Diabetes

The following are precautions for all people with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2:

- Because people with diabetes are at higher than average risk for heart disease, they should always check with their providers before undertaking a new vigorous exercise program. Moderate-to-high intensity (not high-impact) exercises are best for people who are cleared by their providers. For people who have been sedentary or have other medical problems, lower-intensity exercises are recommended initially.

- Strenuous strength training or high-impact exercise is not recommended for people with uncontrolled diabetes. Such exercises can strain weakened blood vessels in the eyes of people with retinopathy. High-impact exercise may also injure blood vessels in the feet.

- People who are taking medications that lower blood glucose, particularly insulin and sulfonylurea drugs, should take special precautions before embarking on a workout program: Monitor glucose levels before, during, and after workouts (glucose levels can swing dramatically during exercise for some people). Avoid exercise if glucose levels are above 300 mg/dL or under 100 mg/dL.

- Inject insulin in sites away from the muscles used during exercise; this can help avoid hypoglycemia.

- Drink plenty of fluids before and during exercise; avoid alcohol, which increases the risk of hypoglycemia.

- Insulin-requiring athletes may need to decrease insulin doses or take in more carbohydrates prior to exercise, but may need to take an extra dose of insulin after exercise (stress hormones released during exercise may increase blood glucose levels).

- Wear good, protective footwear to help avoid injuries and wounds to the feet.

- Some blood pressure drugs may affect exercise capacity. People who use blood pressure medication should consult their doctors on how to balance medications and exercise. People with high blood pressure should also aim to breathe as normally as possible during exercise. Holding your breath can increase blood pressure.

Diabetic Exchange Lists

The objective of using diabetic exchange lists is to maintain the proper balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats throughout the day. People should meet with a dietician or diabetes nutrition expert for help in learning this approach.

In developing a menu, people must first establish their individual dietary requirements, particularly the optimal number of daily calories and the proportion of carbohydrates, fats, and protein. The exchange lists should then be used to set up menus for each day that fulfill these requirements.

The following are some general rules:

- The diabetic exchanges are six different lists of foods grouped according to similar calorie, carbohydrate, protein, and fat content; these are starch/bread, meat, vegetables, fruit, milk, and fat. A person is allowed a certain number of exchange choices from each food list per day.

- The amount and type of these exchanges are based on a number of factors, including the daily exercise program, timing of insulin injections, and whether or not an individual needs to lose weight or reduce cholesterol or blood pressure levels.

- Foods can be substituted for each other within an exchange list but not between lists even if they have the same calorie count.

- In all lists (except in the fruit list) choices can be doubled or tripled to supply a serving of certain foods. (For example, 3 starch choices equal 1.5 cups of hot cereal or 3 meat choices equal a 3-ounce [84 grams] hamburger.)

- On the exchange lists, some foods are "free." These contain fewer than 20 calories per serving and can be eaten in any amount spread throughout the day unless a serving size is specified.

The following are the categories on exchange lists:

Starches and Bread

Each exchange under starches and bread contains about 15 grams of carbohydrates, 3 grams of protein, and a trace of fat for a total of 80 calories. A general rule is that a half-cup of cooked cereal, grain, or pasta equals one exchange. One ounce (28 grams) of a bread product is 1 serving.

Meat and Cheese

The exchange groups for meat and cheese are categorized by lean meat and low-fat substitutes, medium-fat meat and substitutes, and high-fat meat and substitutes. Use high-fat exchanges a maximum of 3 times a week. Fat should be removed before cooking. Exchange sizes on the meat list are generally 1 ounce (28 grams) and based on cooked meats (3 ounces [84 grams] of cooked meat equals 4 ounces [112 grams] of raw meat).

Vegetables

Exchanges for vegetables are 1/2 cup cooked, 1 cup raw, and 1/2 cup juice. Each group contains 5 grams of carbohydrates, 2 grams of protein, and 2 to 3 grams of fiber. Vegetables can be fresh or frozen; canned vegetables are less desirable because they are often high in sodium. They should be steamed or cooked in a microwave without added fat.

Fruits and Sugar

Sugars are included within the total carbohydrate count in the exchange lists. Sugars should not be more than 10% of daily carbohydrates. Each exchange contains about 15 grams of carbohydrates for a total of 60 calories.

Milk and Substitutes

The milk and substitutes list is categorized by fat content similar to the meat list. A milk exchange is usually 1 cup or 8 ounces. Those who are on weight loss or low-cholesterol diets should follow the skim and very low-fat milk lists -- while avoiding the whole milk group. Others should use the whole milk list very sparingly. All people with diabetes should avoid artificially sweetened milks.

Fats

A fat exchange is usually 1 teaspoon, but it may vary. People, of course, should avoid saturated and trans fatty acids and choose polyunsaturated or monounsaturated fats instead.

Calories | 1,200 | 1,500 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 2,200 | |

Starch/Bread | 5 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 13 | |

Meat | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | |

Vegetable | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

Fruit | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

Milk | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

Fat | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Resources

- American Diabetes Association -- www.diabetes.org

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases -- www.niddk.nih.gov

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics -- www.eatright.org

- Food and Nutrition Information Center -- www.nal.usda.gov/fnic

- Endocrine Society -- www.endocrine.org

References

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2020. Diabetes Care. 2020 Jan;43(Suppl 1) clinical.diabetesjournals.org/content/38/1/10.full-text.pdf.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e563-e595. PMID: 30879339 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30879339/.

Atkinson MA, McGill DE, Dassau E, Laffel L. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. In: Melmed S, Auchus RJ, Goldfine AB, Koenig RJ, Rosen CJ eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 14th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 36.

Balk EM, Earley A, Raman G, Avendano EA, Pittas AG, Remington PL. Combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: A Systematic Review for the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):437-451. PMID: 26167912 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26167912/.

Bray GA, Heisel WE, Afshin A, et al. The Science of Obesity Management: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(2):79-132. PMID: 29518206 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29518206/.

Chamberlain JJ, Rhinehart AS, Shaefer CF Jr, Neuman A. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: Synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(8):542-552. PMID: 26928912 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26928912/.

Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LM, Peters AL; Type 1 Diabetes Sourcebook Authors. Type 1 diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(7):2034-2054. PMID: 24935775 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24935775/.

Dungan KM. Management of type 2 diabetes. In: Jameson JL, De Groot LJ, de Kretser DM, et al, eds. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2016:chap 48.

Franz MJ, MacLeod J, Evert A, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition Practice Guideline for Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Systematic Review of Evidence for Medical Nutrition Therapy Effectiveness and Recommendations for Integration into the Nutrition Care Process. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):1659-1679. PMID: 28533169 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28533169/.

Hemmingsen B, Gimenez-Perez G, Mauricio D, Roqué I Figuls M, Metzendorf MI, Richter B. Diet, physical activity or both for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD003054. PMID: 29205264 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29205264/.

Imamura F, O'Connor L, Ye Z, et al. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages, and fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimation of population attributable fraction. BMJ. 2015;351:h3576. PMID: 26199070 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26199070/.

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;63(25 Pt B):2985-3023. PMID: 24239920 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239920/.

Locke A, Schneiderhan J, Zick SM. Diets for Health: Goals and Guidelines. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(11):721-728. PMID: 30215930 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30215930/.

Yu E, Malik VS, Hu FB. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention by Diet Modification: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):914-926. PMID: 30115231 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30115231/.

Reviewed By: Brent Wisse, MD, board certified in Metabolism/Endocrinology, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.