What seemed like a simple family outing for ice cream bars ended up taking science writer Steve Ettlinger on a sometimes mind-boggling mission: He embarked on a journey to get to the bottom of those tongue-tying words found on processed food labels, and to find out where these often mysterious ingredients come from.

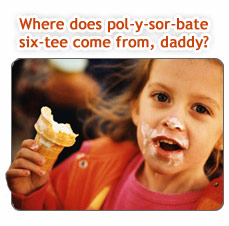

It all started with a few innocent questions about ingredients listed on the ice cream bar wrappers. "What’s pol-y-sor-bate six-tee?" asked Ettlinger’s then sixth-grader son Dylan.

"It’s, uh... ummmm," muttered Steve, wearing the expression of a deer caught in the headlights.

Then his daughter, Chelsea, 6 at the time, asked the humdinger: "Where does pol-y-sor-bate six-tee come from, daddy?"

Like most people, Ettlinger had read ingredient lists on cereal boxes, frozen dinners, and ice cream packages. "But I didn’t really know what I was reading," he admits.

He had to tell his kids the truth: He had no clue what the mysterious substance was. Nor did he know where it came from or why it ended up in ice cream.

"My daughter’s question was the inspiration for me to find out, and to write a book about food ingredients. However, I didn’t want to just do a reference book. I needed a focus," Ettlinger says.

And then the focus came, in all its sweet, gooey, golden splendor -- the Twinkie.

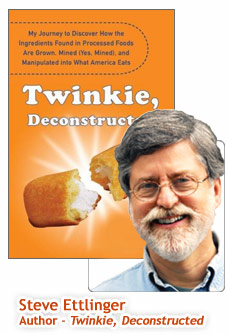

This highly-processed American icon is loaded with food additives. (It was, in fact, included in a collection of modern day artifacts compiled by former President Bill Clinton for a time capsule.) The ingredient list became the chapter outline for Ettlinger’s book, Twinkie, Deconstructed: My Journey to Discover How the Ingredients Found in Processed Foods Are Grown, Mined (Yes, Mined), and Manipulated into what America Eats.

Ettlinger says there’s no mystery about why some 500 million Twinkie snack cakes are sold each year. "People have been attracted to fatty and sweet-tasting things forever. We are hard-wired to like that taste. So if you want something sweet and fatty-tasting, a Twinkie fills the bill very easily."

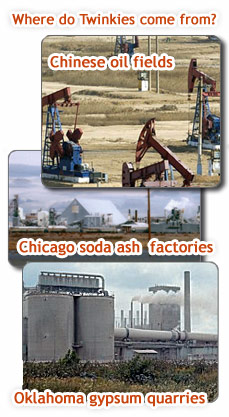

On his wide-ranging, sometimes scary -- and often funny -- adventure to nail down exactly where the Twinkie’s ingredients come from, Ettlinger traveled from the phosphate mines of Idaho to the oil fields of China, from Chicago factories that turn crushed rocks (lime and soda ash) into leavening agents to gypsum quarries in Oklahoma. What he learned illuminates the origin and purposes of ingredients from plain enriched white flour, corn, water, and sugar to chemicals with complex names like "sodium acid pyrophosphate" and "sodium stearoly lactylate." Altogether, they give Twinkies (and many other processed foods) their sweet, soft, creamy, moist, and fatty taste appeal, while helping them sit on shelves, without spoiling, for about a month.

Oh, yeah. The book also answers the questions raised by Ettlinger’s children: Polysorbate 60 works with mono and diglycerides and sodium stearoyl lactylate to form an "emulsifying system." To those of us who read English, these chemicals keep water and air bubbles in a Twinkie’s creamy filling. Everything has its place in life and baked goods.

Although a highly experienced science writer, Ettlinger says he was surprised by much of what he learned while tracking down his tale of food additives. "I was naively under the impression that vitamins came from seeds and fruits and vegetables, things you squeeze and otherwise process from foods. I was amazed to find out that many of them are brewed or even made from petroleum," he says. "Vitamins that are in enriched flour come mostly from China, and the Chinese are not really open about how they do things. We don’t know a lot about the companies that make these. It is troubling."

While researching his book, the health dangers of trans-fats were a hot news topic, and companies were scrambling to reformulate recipes to remove these potentially artery-clogging additives from their products. "When I’d ask about the other additives the manufacturers’ engineers were busy making, and questioned how they know the ingredients are safe or how the additives break down in the body, I would be answered by two non-specific clichés – ‘we’ve been using it for 20 or 60 or whatever years, so of course it is safe’ and ‘it has all been tested and approved.’"

What does he hope Twinkie, Deconstructed accomplishes? "I want to open people’s minds to learning what it is they are eating," he answers. "There’s no reason to be paranoid, just be vigilant."

Ettlinger stresses he’s not on an anti-junk food campaign. "There’s nothing wrong with these ingredients, per se, but if you are concerned about your good health, it makes more sense to have a Twinkie or similar snack cake only every now and then, and concentrate on eating mostly fresh fruits and vegetables. That’s what all the good research says about eating the healthiest way," he says.

"A lot of people contact me and are appalled that so many food additive ingredients come from industrial processes that burn up tons and tons of fossil fuel and might possibly be harmful or, at least, not great for our health. If you want to eat healthier and also eat in a way that might be a little bit better for the health of the planet, I advise eating local fruits and vegetables that have been sustainably raised near where you live. But, obviously, you can’t do that for all your foods, and I, for one, don’t think you should."

On a personal level, Ettlinger says writing Twinkie, Deconstructed has made him more aware of where food comes from. "It is very important. Food is literally essential to your life. I think that after people read Twinkie, Deconstructed, they are more likely to treat their local farmers’ markets with more attention and more respect. I know I do."

A former chef, Ettlinger does most of the cooking for his wife and two children. "I definitely have instilled in my children a taste for whole foods and fresh foods. We certainly do avoid processed foods, not because of any religious-like mantra that they are bad, but because it is really healthier to eat fresh, whole foods, especially fruits and vegetables. And when you not only prepare good food but know something about how it was grown and that it is fresh, it is really that much more enjoyable to eat."

|