Cholesterol - InDepth

Highlights

Cholesterol

A blood test is used to measure cholesterol levels. Besides total cholesterol, a lipid profile test also includes measurements of LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, also called bad cholesterol), HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, also called good cholesterol), and triglycerides.

New Cholesterol Guidelines

Over the past few years, a different approach to treating abnormal cholesterol levels has been developed. Previous guidelines recommended that doctors use specific target goals for LDL depending on patient risk factors. The newer guidelines take a somewhat different approach:

- The treatment emphasis now focuses on reducing the risk for diseases caused by atherosclerosis, including abnormal cholesterol, but usually not by targeting subsequent cholesterol lab results precisely.

- Several cardiovascular risk calculators are available which consider a person's gender, age, race, total cholesterol, HDL, blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking to estimate their risk for having a heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years. Based on these results, your doctor may recommend treatment with a cholesterol-lowering statin or other drugs.

- Heart-healthy lifestyle changes (diet, exercise, smoking cessation, and weight control) still remain the foundation for cholesterol treatment at all ages. Lifestyle management is used before, and during, drug therapy.

Drug Therapy

Guidelines recommend drug therapy based on a person's risk for heart disease, stroke, and other problems caused by atherosclerosis:

- Primary prevention refers to risk reduction in those who do not yet have evidence of cardiovascular disease.

- Secondary prevention refers to risk reduction in those who have evidence of cardiovascular disease.

- Statins are the first choice in virtually all patients with abnormal LDL-cholesterol levels to prevent cardiovascular disease.

- When to start statins and what dose to use is based on a patient's risk and current atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

- Newer, biological drugs have been approved for reducing the LDL cholesterol level in certain high risk scenarios.

Lifestyle Changes

The key lifestyle changes to improve unhealthy cholesterol levels are:

- Heart-healthy diet (with emphasis on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains).

- Regular physical activity (The AHA recommends performing 30 minutes of moderate exercise 5 days a week for a total of 150 minutes a week, or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise a week).

- Healthy body weight (with a doctor's help when necessary).

- Don't smoke.

- Control of high blood pressure and diabetes (for patients who also have these conditions).

Introduction

Lipids are the building blocks of the fats and fatty substances found in animals and plants. They include cholesterol, triglycerides, fatty acids, phospholipids, and others. Lipids do not dissolve in water and are usually transported in blood and other body fluids in the form of lipoproteins. Lipids serve essential functions in the body, including:

- Structural components of all cell membranes

- Energy source

- Signaling molecules involved in multiple cellular processes

- Precursors for other lipid molecules, hormones, vitamins, and others

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is present in all animal cells and in animal-based foods (but not present in plants). In spite of its bad press, cholesterol is an essential nutrient necessary for many functions, including:

- Repairing cell membranes

- Manufacturing vitamin D in the skin

- Producing hormones, such as estrogen and testosterone

- Possibly helping cell connections in the brain that are important for learning and memory

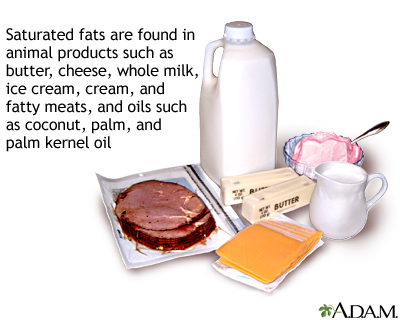

Regardless of these benefits, when cholesterol levels rise in the blood, they can have dangerous consequences, depending on the type of cholesterol. Although the body acquires some cholesterol through diet, about two-thirds is manufactured in the liver, its production stimulated by saturated fat. Saturated fats are found in animal products (meat, egg yolks, and high-fat dairy products) and tropical plant oils (palm, coconut).

Saturated fats are found predominantly in animal products, such as meat and dairy products, and are strongly associated with higher cholesterol levels. Tropical oils -- such as palm, palm kernel, coconut, and cocoa butter -- are also high in saturated fats.

Triglycerides

Triglycerides are composed of glycerol and fatty acid molecules. They are the basic chemicals contained in fats in both animals and plants. High levels of triglycerides, especially in combination with low levels of HDL, are associated with increased risk for heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and fatty liver disease.

Lipoproteins

Lipoproteins are protein spheres that transport cholesterol, triglyceride, or other lipid molecules through the bloodstream. Most of the vascular effects of cholesterol and triglyceride actually depend on lipoproteins.

Lipoproteins are categorized into five types according to size and density. They can be further defined by whether they carry cholesterol or triglycerides.

Cholesterol-Carrying Lipoproteins

These are the lipoproteins commonly referred to as cholesterol.

- Low density lipoproteins (LDL), often called "bad" cholesterol)

- High-density lipoproteins (HDL), the smallest and densest (often called "good" cholesterol)

Triglyceride-Carrying Lipoproteins

- Intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL) tend to carry triglycerides.

- Very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) tend to carry triglycerides.

- Chylomicrons or ultra low density lipoproteins (UDL) are the largest in size and lowest in density. Chylomicrons tend to carry triglycerides.

Effects of Lipoproteins and Triglycerides on Heart Disease

Low Density Lipoproteins (LDL), the "Bad" Cholesterol

The main villain in the cholesterol story is low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Heart disease is least likely to occur among people with the lowest LDL levels. Lowering LDL is the primary goal of cholesterol drug and lifestyle therapy.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) transports about 75% of the blood's cholesterol to the body's cells. It is normally harmless. However, if it is exposed to a process called oxidation, LDL can penetrate and interact dangerously with the walls of the artery, producing a harmful inflammatory response. Oxidation is a natural process in the body that occurs from chemical combinations with unstable molecules. These molecules are known as oxygen-free radicals or oxidants.

In response to oxidized LDL, the body releases various immune factors aimed at protecting the damaged arterial walls. Unfortunately, in excessive quantities they cause inflammation and promote further injury to the areas they target.

High Density Lipoproteins (HDL), the "Good" Cholesterol

High density lipoprotein (HDL) appears to benefit the body in several ways:

- It removes cholesterol from the walls of the arteries and returns it to the liver for disposal from the body.

- It helps prevent oxidation of LDL. (HDL may have antioxidant properties.)

- It may also fight inflammation.

HDL helps keep arteries open and reduces the risk for heart attack. High levels of HDL (above 60 mg/dL) may be nearly as protective for the heart as low levels of LDL. HDL levels below 40 mg/dL are associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

Triglycerides

Triglycerides interact with HDL cholesterol in such a way that HDL levels fall as triglyceride levels rise. High triglycerides may pose other dangers, regardless of cholesterol levels. For example, they may be associated with blood clots that form and block the arteries. High triglyceride levels are also associated with the inflammatory response -- the harmful effect of an overactive immune system that can cause considerable damage to cells and tissues, including the arteries. Very high triglycerides can also cause pancreatitis a potentially life-threatening condition.

Risk Factors

Unhealthy cholesterol levels (low HDL, high LDL, and high triglycerides) increase the risk for heart disease and heart attack. Some risk factors for cholesterol can be controlled (such as diet, exercise, and weight) while others cannot (such as age, gender, and family history).

Age and Sex

From puberty on, men tend to have lower HDL (good cholesterol) levels than women. One reason is that the female sex hormone estrogen is associated with higher HDL levels. Because of this, premenopausal women generally have lower rates of heart disease than men.

After menopause, as estrogen levels decline, women catch up in their rates of heart disease. Throughout the post-menopausal years, HDL levels decrease and LDL (bad cholesterol) and triglyceride levels increase. For men, LDL and triglyceride levels also rise as they age and the risks for heart disease increase as well. (There is some evidence that high triglyceride levels carry more risks for women than men.) Heart disease is the main cause of death for both men and women.

Children and Adolescents

Children who have abnormal cholesterol levels are at increased risk of developing heart disease later in life. However, it is difficult to distinguish "normal" cholesterol levels in children. Cholesterol levels which are normally very low at birth tend to naturally rise sharply until puberty, decrease sharply, and then rise again later in life.

Genetic Factors and Family History

Genetics can play a major role in determining a person's blood cholesterol levels. (Children from families with a history of premature heart disease should be tested for cholesterol levels after they are 2 years old.) Genes may influence whether a person has low HDL levels, high LDL levels, high triglycerides, or high levels of other lipoproteins, such as lipoprotein(a). There are several types of inherited cholesterol disorders.

Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)

FH is a genetic disorder that causes high cholesterol levels, particularly LDL, and premature heart disease. There are two forms of FH:

- Heterozygous FH, in which the genetic mutation is inherited from one parent, occurs in about 1 in 500 people. It increases the risk for heart attack between the ages of 40 to 60.

- Homozygous FH, in which the genetic mutation is inherited from both parents, is much rarer. It occurs in about 1 in 1 million people. People who have homozygous FH are at risk for having extremely severe hypercholesterolemia, many experiencing heart attack or death before the age of 30.

Familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency is a group of rare genetic disorders that causes depletion of the enzyme lipoprotein lipase. This enzyme helps in the removal of lipoproteins that are rich in triglycerides. People who are deficient in lipoprotein lipase have high levels of cholesterol and fat in their blood.

Lifestyle Factors

Diet

The primary dietary elements that lead to unhealthy blood cholesterol include saturated fats (found mainly in red meat and high-fat dairy products) and trans fatty acids (found in fried foods and some commercially baked food products). Shellfish and egg yolks are also high in dietary cholesterol. Large amounts of added sugars raise triglyceride levels.

Weight

Being overweight or obese increases the risks for unhealthy cholesterol levels.

Exercise

Lack of exercise can contribute to weight gain, decreases in HDL levels, and increases in LDL, triglycerides, and total cholesterol levels.

Smoking

Smoking reduces HDL cholesterol and promotes build-up of fatty deposits in the coronary arteries.

Alcohol

Heavy consumption of alcohol can increase triglyceride levels.

Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Type 2 Diabetes

In the United States, obesity is at epidemic levels in all age groups. The effect of obesity on cholesterol levels is complex. Overweight individuals tend to have high triglyceride and LDL levels and low HDL levels. This combination is a risk factor for heart disease. Obesity also causes other effects such as high blood pressure and an increase in inflammation that pose major risks to the heart.

Obesity is particularly dangerous when it is one of the components of the metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome consists of:

- Obesity marked by abdominal fat

- Unhealthy lipid levels (low HDL levels, high triglycerides)

- High blood pressure

- Insulin resistance

Metabolic syndrome is a pre-diabetic condition that is significantly associated with heart disease and higher mortality rates from all causes. Obesity is also strongly associated with type 2 diabetes, which itself poses a significant risk for high cholesterol levels and heart disease.

Children who are overweight are at higher risk for high triglycerides and low HDL, which may be directly related to later unhealthy cholesterol levels. Childhood LDL levels and body mass index (BMI) are strongly associated with cardiovascular risk during adulthood. Overweight and obese children who have high cholesterol should also get tested for high blood pressure, diabetes, and other conditions associated with metabolic syndrome.

Other Medical Conditions

High Blood Pressure

High blood pressure (hypertension) does not affect your cholesterol level, does contribute to the thickening of the heart's blood vessel walls, which can worsen atherosclerosis (accumulated deposits of cholesterol in the blood vessels). High blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes all act together to increase the risk for developing heart disease.

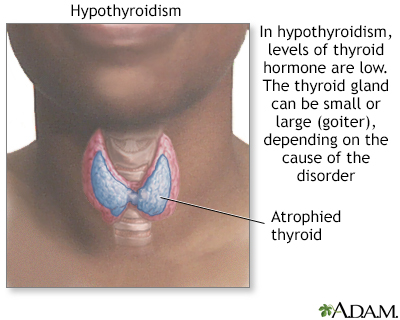

Hypothyroidism

Low thyroid levels (hypothyroidism) are associated with elevated total and LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Treating the thyroid condition can significantly reduce cholesterol levels. Research is mixed on whether mild hypothyroidism (subclinical hypothyroidism) is associated with unhealthy cholesterol levels.

Hypothyroidism is a decreased activity of the thyroid gland which may affect all body functions. In this condition, the rate of metabolism slows, causing mental and physical sluggishness. The most severe form of hypothyroidism is myxedema, which is a medical emergency.

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

Women with this endocrine disorder may have increased risks for high triglyceride and low HDL levels. This risk may be due to the higher levels of the male hormone testosterone associated with this disease.

Other Risk Factors

Medications

Certain medications such as specific antiseizure drugs, corticosteroids, and isotretinoin (Accutane) may increase lipid levels.

Complications

Heart Disease

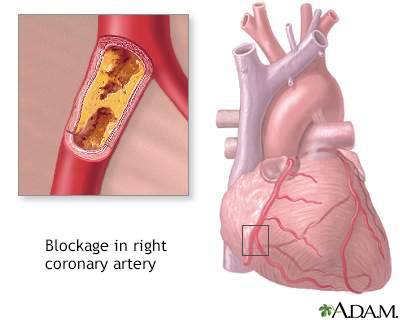

Atherosclerosis is a common disorder of the arteries. Fat, cholesterol, and other substances collect in the walls of arteries. Larger accumulations are called atheromas or plaque and can damage artery walls and block blood flow. Severely restricted blood flow in the heart muscle leads to symptoms such as chest pain.

Unhealthy cholesterol, particularly low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, forms a fatty substance called plaque, which builds up on the arterial walls of the heart. Smaller plaques remain soft, but older, larger plaques tend to develop fibrous caps with calcium deposits.

The long-term result is atherosclerosis. The heart is endangered in two ways by this process:

- The calcified and inelastic arteries eventually become narrower (a condition known as stenosis). As this process continues, blood flow slows and prevents sufficient oxygen-rich blood from reaching the heart. This condition can lead to angina (chest pain) and when atherosclerotic plaques are damaged (e.g. Rupture) can lead to sudden blockages and heart attack. When damage is sufficient to impair the pumping of the heart, heart failure can result.

- Smaller unstable plaques may rupture, triggering the formation of blood clots on their surface. The blood clots block the arteries and are important causes of heart attack.

This process is accelerated by other risk factors including high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and a sedentary lifestyle. When more than one of these risk factors is present, the risk is compounded.

Coronary Artery Disease

The end result of atherosclerosis is coronary artery disease. Coronary artery disease, sometimes referred to simply as "heart disease" or ischemic heart disease, is the leading cause of death in the U.S.

Studies consistently report a higher risk for death from heart disease with high LDL cholesterol levels. Even moderate elevation of LDL levels increases the chance of heart disease when other risk factors are present. The higher the cholesterol, the greater the risk.

Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is caused by the buildup of plaque in the feet, legs, hands, and arms. It most often occurs in the legs. PAD is associated with atherosclerosis. Lower levels of HDL and high triglyceride levels also increase the risk for PAD.

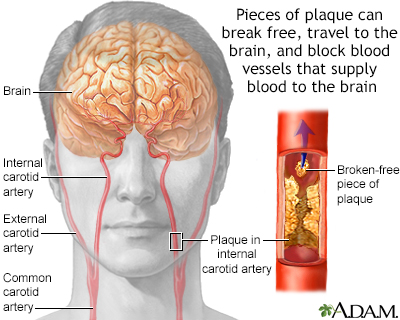

Stroke

Having adequate levels of HDL may be the most important lipid-related factor for preventing ischemic stroke, a type of stroke caused by blockage of the arteries that carry blood to the brain. HDL may even reduce the risk for hemorrhagic stroke, a much less common type of stroke caused by bleeding in the brain that is associated with low overall cholesterol levels.

The build-up of plaque in the internal carotid artery may lead to narrowing and irregularity of the artery's channel, preventing proper blood flow to the brain. More commonly, as the narrowing worsens, clots form on the plaque and can break free, travel to the brain, and block blood vessels that supply blood to the brain. This leads to stroke, with possible paralysis, speech impairment, or other deficits.

The effects of high total cholesterol and LDL levels on ischemic stroke are less clear. Some research suggests that the risk for ischemic stroke increases when total cholesterol is high. Other studies suggest that high cholesterol poses a risk for stroke only when specific proteins associated with inflammation are present.

Symptoms

There are no warning signs for high LDL and other unhealthy cholesterol levels. When symptoms finally occur, they usually take the form of angina (chest pain), heart attack, or stroke. When buildups occur in leg arteries, patients may have discomfort with walking (called "claudication"). In men, erectile dysfunction may be another symptom of atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis is a disease of the arteries in which fatty material is deposited in the vessel wall, resulting in narrowing and eventual impairment of blood flow. Severely restricted blood flow in the arteries to the heart muscle leads to symptoms such as chest pain. Atherosclerosis shows no symptoms until a complication occurs.

Diagnosis

Blood tests can easily measure cholesterol levels. A lipid profile includes: LDL, total cholesterol, HDL, and triglycerides. It is also possible to measure LDL levels by themselves, but LDL levels can be reliably calculated using the other values, unless the triglycerides are very high.

To obtain an accurate cholesterol reading, doctors advise:

- Do not eat or drink anything but water for 8 to 12 hours before the test. (Some recent studies indicate that fasting is not really necessary for routine screening. Check with your doctor.)

- If the test results are abnormal, a second test should be performed between 1 week and 2 months after the first test.

Screening Guidelines

Periodic cholesterol testing is recommended in all adults, but the major national guidelines differ on the age to start testing.

- Recommended starting ages are between 20 to 35 for men and 20 to 45 for women.

- Adults with normal cholesterol levels do not need to have the test repeated for 5 years unless changes occur in lifestyle (including weight gain and diet).

- Adults with a history of elevated cholesterol, diabetes, kidney problems, heart disease, and other conditions require more frequent testing.

Screening with a fasting lipid profile is recommended for children who:

- Have risk factors such as a family history of high cholesterol, and history of heart attacks before age 55 for men and before age 65 for women. Screening should begin as early as age 2 and no later than age 10.

- Are overweight or obese (above the 85th percentile for weight) or have diabetes. If the child's cholesterol level tests normal, retesting is recommended in 3 to 5 years.

People already being treated for high cholesterol may have tests periodically to ensure treatment is working and is being tolerated (especially by the liver). However the new guidelines de-emphasize repeat testing.

Other Tests

If the risk-based calculation for statin therapy is uncertain, the doctor may order three additional tests recommended by the ACC/AHA guidelines:

- C-reactive Protein (CRP). CRP is produced in the liver. CRP levels increase when there is inflammation throughout the body. A CRP level 2.0 mg/L or greater indicates increased risk for heart disease. CRP is measured by a blood test.

- Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI). The ABI test compares blood pressure readings in the ankles and arms to evaluate circulation. Measurements below 0.9 suggest possible blockage of the arteries. The ABI test is similar to a blood pressure exam but the cuff is placed around the ankles. This test is typically used to diagnose peripheral artery disease.

- Coronary Calcium Scan. A computed tomography (CT) scan is used to detect calcium deposits on the arterial walls. A high coronary artery calcification score (above 300 Agatston units) indicates increased risk for heart disease. Routine screening with this test is not recommended.

Other possible tests your doctor may order include:

- Carotid Intima-Media Thickness. This test uses an ultrasound scan to obtain a very precise measurement of the wall of the carotid artery. If your thickness is high your doctor may prescribe drug therapy.

- Lp(a). Lipoprotein(a) is a lipoprotein that is associated with coronary artery disease and stroke. However, there is no proven benefit to date that lowering these levels will result in fewer cardiovascular events. If your levels are elevated, your doctor may prescribe lipid-lowering therapy.

- LP PLA2. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 is a marker of vascular inflammation which is associated with heart disease and stroke. If your levels are elevated, your doctor may prescribe lipid-lowering therapy.

- Apolipoprotein B (apoB or apoB 100). Apolipoprotein B is a component of lipoproteins like LDL and is associated with cardiovascular disease risk. Similar to LDL-C, apoB may be used to help with decisions on lipid-lowering therapy.

Treatment

General Treatment Approaches

Lifestyle changes (such as diet, weight control, exercise, and smoking cessation) are the first line of defense for treating unhealthy cholesterol levels. If levels and other risk factors still remain high, drug treatment is an effective next step.

Statins are the first-line drugs for lowering high LDL levels, and reducing the risk for heart disease and stroke. A statin drug is used along with healthy lifestyle habits, not in place of them.

In the past, the choices regarding when and how aggressively to treat hyperlipidemia was driven largely by your LDL and HDL cholesterol level. Doctors advised most adults to target a total cholesterol level of less than 200 mg/dL and an LDL of less than 100 mg/dL. In some people at very high risk, the targeted level was even lower.

However, experts on cholesterol realized there was no solid scientific evidence to support the target number treatment approach, especially in people with no cardiovascular disease. As a result, newer guidelines take what is called a risk-based approach of treating the patient, rather than just treating the lab result. Along with the cholesterol level, other factors which may increase a patient's risk for heart disease are considered. All of this information is then used to decide the following:

- Whether to use statin drugs to treat unhealthy cholesterol levels

- How to choose between lower and higher doses of lower and higher potency statins

- Which other drugs may be used

Candidates for Statin Therapy

Secondary prevention refers to treating unhealthy cholesterol levels in those with a history of heart disease, stroke, or narrowing of the arteries to the brain, intestines, kidneys, or legs (cardiovascular disease).

- Almost all people with these health problems will be treated with higher doses of statins, if tolerated.

- For most of these patients, the aim is to reduce LDL-cholesterol by at least half.

- In people with very high risk for these problems, the aim with statin therapy is to reduce LDL-C to below 70 mg/dL.

- Other drugs may be needed to reach these goals, such as PCSK9 inhibitors and ezetimibe.

Primary prevention refers to treatment of people who have no known cardiovascular disease but are thought to be at increased risk. Treatment recommendations differ based upon a person's risk of cardiovascular disease and the risk for side effects caused by statins.

If you have diabetes and an LDL-C level between 70 and 189 mg/dL (1.8 to 4.9 mmol/L):

- In those 40 to 75 years of age, you will be given moderate doses of statins. The goal is to reduce your LDL-C I by a little less than half.

- In those with many risk factors for ASCVD, or those 50 to 75 years of age, you may be given higher doses of statins. The goal is to reduce LDL-C by over half.

If you do not have diabetes, are between the ages of 40 and 75 years, and have an LDL-C level between 70 and 189 mg/dL (1.8 to 4.9 mmol/L):

- You or your healthcare provider should calculate your risk of having a heart attack or stroke within 10 years. (See section on risk calculators below).

- In those who have a 7.5% or higher risk, moderate doses of statins are most often recommended. The goal is to reduce your LDL-C I by a little less than half.

- In those with a very high risk of heart attack or stroke, higher doses of statins may be used.

- In those who have less than a 7.5% risk of heart attack or stroke, most of the time your provider will discuss lifestyle changes.

If you are an adult with a LDL-C 190 mg/dL (4.9 mmol/L) or higher:

- You will likely be given higher doses of statins.

- If the LDL-C level remains above 100 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), adding ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor may be considered.

Adults over 75 years who are otherwise healthy may be a candidate for drug therapy for elevated cholesterol levels. However, careful consideration should take place for older adults who appear to have a limited life span due to other illnesses that are present.

Heart Disease Risk Calculation

The ACC/AHA has designed a special "risk calculator" tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate that health care providers can use to calculate a person's 10-year cardiovascular disease risk.

The ACC/AHA recommends that doctors enter the following factors into a "risk calculator" to determine a person's overall risk for cardiovascular disease:

- Sex

- Age

- Race (white, African American, or other)

- Total cholesterol

- LDL (bad cholesterol)

- HDL (good cholesterol)

- Blood pressure (systolic and diastolic blood pressure)

- Currently treated for blood pressure

- Currently treated with a statin

- Currently treated with aspirin

- Diabetes

- Smoking

This risk calculator is designed for people age 40 to 79 years old who do not have existing or prior heart disease.

If the risk calculation seems uncertain, a doctor may consider additional factors. They include family history of premature heart disease, increased lifetime heart disease risk, and sometimes the results of other diagnostic tests such as C-reactive protein level, ankle-brachial index, and coronary artery calcification score.

The ACC/AHA's position is that individual patient preferences are an important part of the new guidelines. All treatment options should begin with a conversation between the doctor and patient, including discussing how people feel about the risks and benefits of drug therapy. In addition, lifestyle modification is the most important component for heart disease risk reduction. As with other guidelines, recommendations are likely to change in the future when more information is available from large research studies.

Lifestyle Changes

The most important first step for improving cholesterol levels and reducing the risk for heart disease and stroke is to make heart-healthy lifestyle changes. Even when drug therapy is used, lifestyle measures are critical companions.

General Guidelines for Healthy Lifestyle

The main lifestyle principles to reduce unhealthy cholesterol levels include:

- Consume a heart-healthy diet (with emphasis on vegetables, fruits, and whole grains)

- Engage in regular physical activity (30 minutes per day for a total of 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity or 75 minutes per week of vigorous exercise)

- Maintain a healthy body weight (under a doctor's supervision when necessary)

- Don't smoke

- Control high blood pressure and diabetes (for people who also have these conditions)

Heart-Healthy Diets

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) joint dietary guidelines for reducing unhealthy cholesterol levels recommend:

- Make vegetables, fruits, and whole grains the focus of your diet

- Include low-fat dairy products, poultry, fish, legumes (beans), nontropical vegetable oils, and nuts

- Limit intake of sweets, sugar-sweetened beverages, and red meats

There are many dietary approaches for protecting heart health, such as the Mediterranean Diet, which emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and healthy types of fats. The DASH diet is very effective for patients with high blood pressure and others who need to restrict sodium (salt) intake. Other heart-healthy diet plans include the American Heart Association diet and the USDA Food Pattern.

Doctors generally agree on the following recommendations for heart protection:

- Choose fiber-rich food (whole grains, legumes, and nuts) as the main source of carbohydrates, along with a high intake of fruits and vegetables. Walnuts in particular have cholesterol-lowering properties and are a good source of antioxidants and alpha-linolenic acid.

- Avoid saturated fats (found mostly in animal products and tropical plant oils) and trans fatty acids (found in hydrogenated fats and many commercial products and fast foods). Choose unsaturated fats (particularly omega-3 fatty acids found in vegetable [olive, canola] and fish oils). For dairy products, choose nonfat or low fat over whole fat.

- For proteins, choose fish, poultry, and beans instead of red meat.

- Fish is particularly heart protective. It contains the omega-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic (EPA), which have significant benefits for the heart, particularly for lowering triglyceride levels. Fish oil supplements do not generally provide the same benefits as fish.

- Avoid added sugars such as those found in sugar-sweetened beverages.

- Limit sodium (salt) intake to no more than 2,400 mg a day. Some people, such as those with high blood pressure, may need to restrict sodium intake to no more than 1,500 mg/day.

After starting a heart healthy diet, it generally takes an average of 3 to 6 months before any noticeable reduction in cholesterol occurs. However, some people see improved levels in as few as 4 weeks.

Weight Management

A healthy weight is very important for healthy cholesterol levels. For people who are overweight or obese, losing even a modest amount of weight has significant health benefits -- even if an ideal weight is not achieved. There is a direct relationship between the amount of weight lost and an improvement in cholesterol.

In particular, triglyceride is closely linked to weight: a sustained 3% to 5% weight loss can significantly reduce unhealthy triglyceride levels. Even greater amounts of weight loss can help improve LDL and HDL levels. Weight loss also helps reduce the need for blood pressure medication, improves blood glucose (sugar) levels, and lowers the risk for developing type 2 diabetes.

Obesity is now considered and treated as a disease, not a lifestyle issue. Doctors' understanding of weight issues has evolved. Scientific evidence has shown that weight gain is a complex process, and weight loss involves more than simple willpower. What is clear is that excess weight contributes to many health problems, including increased risk for cardiovascular disease conditions.

Your doctor should check your body mass index (BMI) at least once a year. You can check your BMI with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website BMI calculator.

The BMI estimates how much you should weigh based on your height:

- Overweight is a BMI of 25 to 29.9

- Obese is a BMI of over 30

Guidelines recommend your doctor create an individualized weight loss plan for you if you are overweight or obese. The plan should include three components:

- Reduced Calorie Diet. Your doctor should help you select an eating plan that will cut calories and perhaps restrict certain food types (such as fats or carbohydrates). Your doctor may make specific recommendations depending on your cholesterol profile and other factors. For example, a low-calorie, low-fat diet can be very effective for reducing LDL levels. (Your personal and cultural food preferences should also be considered.) Your doctor may refer you to a registered dietician or nutritionist for counseling.

- Behavioral Strategies. People need to consider how to set weight loss goals, monitor weight, track food and calorie intake, change shopping habits and food storage environments, and establish fitness routines. People may benefit from individual, group, or telephone counseling sessions.

- Increased Physical Activity. People should aim for 200 to 300 minutes of physical activity a week (about 40 minutes a day of moderate to intensive aerobic exercise).

A weight loss of 5% to 10% within the first 6 months of starting these changes can help improve cholesterol levels and other health indicators. If you have risk factors for heart disease or diabetes and do not achieve weight loss from diet and lifestyle changes alone, your doctor may recommend adding a prescription medication to your weight loss plan. For people who have a very high BMI and several cardiovascular risk factors (such as diabetes and high blood pressure), bariatric surgery may be considered.

Exercise

Inactivity is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, on par with smoking, unhealthy cholesterol, and high blood pressure. In fact, studies suggest that people who change their diet in order to control cholesterol only achieve a lower risk for heart disease when they also follow a regular aerobic exercise program. Resistance (weight) training offers a complementary benefit to aerobics.

Even moderate exercise reduces the risk of heart attack and stroke. Current guidelines recommend at least 40 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on three or more days per week for a total of 200 to 300 minutes per week.

Quitting Smoking

Cigarette smoking lowers HDL and is directly responsible for many deaths from heart disease. The importance of breaking this habit cannot be emphasized enough. Once a person quits smoking, HDL cholesterol levels rise within weeks or months to levels that are equal to their nonsmoking peers. Passive smoking also reduces HDL levels and increases the risk of heart disease in people exposed to second-hand smoke. Cigarette smoking is also associated with high blood pressure.

Alcohol

A number of studies have found heart protection from moderate intake of alcohol (one or two drinks a day). Moderate amounts of alcohol may help raise HDL levels. Although red wine is most often cited for healthful properties, any type of alcoholic beverage appears to have similar benefit. However, the potential benefits of moderate drinking may be offset by the risk for alcohol use disorder and other diseases. People with high triglyceride levels should drink sparingly, or not at all, because even small amounts of alcohol can significantly increase blood triglycerides. Pregnant women, women at risk for breast cancer, anyone who cannot drink moderately, and people with liver disease should not drink at all. Because alcohol can be toxic to the heart muscle, some patients with heart disease, specifically heart failure, may be counseled to avoid alcohol. Drinking alcohol in any amount may increase your risk for certain types of cancer.

Herbs and Supplements

Manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

The following natural remedies are of interest for cholesterol control:

- Garlic. Contrary to popular belief, neither raw garlic nor garlic supplements significantly reduce LDL cholesterol levels.

- Policosanol. Policosanol is a nutritional supplement derived from sugar cane that has been promoted as having lipid-lowering benefits. However, rigorous research has not shown that policosanol has any effect on reducing LDL levels.

- Red Yeast Rice. Red yeast rice is used in traditional Chinese medicine. The FDA warns that red yeast rice dietary supplement products sold as treatments for high cholesterol contain the same chemicals as the statin drugs, but these products are not standardized for purity, safety, and effectiveness.

Medications

Statins

Statins are the most effective drugs for lowering LDL (bad cholesterol) levels and reducing the risk for heart disease and stroke. Statins inhibit the liver enzyme HMG-CoA reductase, which the body uses to manufacture cholesterol.

Current guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend a statin drug as the first-line drug treatment for patients at risk for cardiovascular disease. Other cholesterol-lowering medications are not as effective as statins and are not recommended, except in rare cases.

Depending on your LDL cholesterol level, presence of atherosclerotic heart disease, 10-year risk for heart disease, and whether or not you have diabetes, your doctor will recommend either a moderate-intensity or high-intensity statin therapy dosage plan. The exact dosage will depend on the statin drug the doctor prescribes for you.

Once you have been started on a statin the recommended dosage is maintained. For the most part, there is no need to monitor LDL levels for response.

If a particular statin drug does not work for you, or if you experience significant side effects, your doctor may switch you to a different statin drug. In general, if multiple statins are not tolerated, other statin lowering medicines are generally not recommended.

Brands

Statins approved in the U.S. include:

- Lovastatin (Mevacor, generic)

- Pravastatin (Pravachol, generic)

- Simvastatin (Zocor, generic)

- Atorvastatin (Lipitor, generic)

- Fluvastatin (Lescol)

- Pitavastatin (Livalo)

- Rosuvastatin (Crestor)

Some statins come as fixed-dose combination drugs, which combine two drugs in one pill. Examples include:

- Sitagliptin/simvastatin (Juvisync) for people with high cholesterol and diabetes.

- Amlodipine/atorvastatin (Caduet) for people with high cholesterol and high blood pressure.

- Ezetimibe/simvastatin (Vytorin) and ezetimibe/atorvastatin (Liptruzet), which combines two lipid-lowering drugs that act through different mechanisms: statins lower cholesterol synthesis in the body and ezetimibe lowers cholesterol absorption from the intestine.

- Simvastatin/niacin (Simcor) and lovastatin/niacin (Advicor) also combine a statin with another lipid lowering drug, niacin, which lowers LDL and triglycerides, and raises HDL levels.

Side Effects

Statin side effects may include diarrhea, constipation, upset stomach, muscle and joint pain, tendon problems, headache, fatigue, and forgetfulness or memory loss. More serious side effects include liver and muscle damage. People should immediately tell their doctor about any unusual muscle discomfort or weakness, fever, nausea or vomiting, or darkening of urine color.

Statins can affect the results of liver tests. Liver enzyme tests should be performed before starting statin therapy. Liver damage is rare but can occur, particularly at higher doses. Tell your doctor if you have symptoms that indicate liver problems such as unusual fatigue, loss of appetite, upper belly pain, dark-colored urine or yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes.

A specific safety concern with statins is an uncommon muscle disease called myopathy, in which a person may experience muscle pains and certain lab tests may be elevated. Severe myopathy called rhabdomyolysis can lead to kidney failure, but fortunately its occurrence is very rare. The risk for myopathy/rhabdomyolysis is highest at higher doses and in older people (over 65 years), those with hyperthyroidism, and those with renal insufficiency (kidney disease).

Rosuvastatin (Crestor) may in particular increase the risk for myopathy, especially when given at the highest dose level (40 mg). The FDA advises that people should not start therapy at a high dose. In addition, people of Asian heritage appear to metabolize the drug differently and should start treatment at the lowest rosuvastatin dose (5 mg) and 20 mg is generally considered the maximum dose for these people. Maximal doses of simvastatin and lovastatin also appear to increase the risk of myopathy.

Other Safety Concerns

Statins are recommended as the best drugs for improving cholesterol and lipid levels in people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. However, they may increase blood glucose levels in some people, especially when taken in high doses. They may also increase the risk for developing type 2 diabetes in people with risk factors.

There is evidence that statins may increase the risk for developing cataracts.

Interactions with Drugs and Food

Statins may have some adverse interactions with other drugs. People should tell their doctors about any other medications they are taking. Medications that should not be taken along with statins include protease inhibitors, telaprevir, cyclosporine, macrolide antibiotics, and certain antifungals. Grapefruit juice and Seville oranges can increase the blood levels of certain statins.

Other Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs

Statins are the primary drugs for treating cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular disease risk. They have replaced the other drugs that were used for lowering cholesterol. These other drugs are still available but the value of their use when statins have not been tolerated or successful enough remains unclear.

Fibrates

Fibrates are generally reserved for people with extremely high triglyceride levels or people with high cholesterol who cannot tolerate a statin drug.

Gemfibrozil (Lopid, generic) is the most commonly prescribed fibrate. Other fibrates include fenofibrate (TriCor, Lofibra) and fenofibric acid (Trilipix). These drugs have many side effects. They can cause gallstones, abnormal heart rhythms, and muscle problems (myopathy), which may lead to kidney damage. A fibrate should only be carefully used in combination with a statin because of increased risk for myopathy.

Niacin

For many years, high doses of niacin (nicotinic acid or vitamin B3) were considered a treatment option for low HDL cholesterol and high LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Research now suggests that niacin does not add to the benefit of a statin alone for reducing the risk of cardiovascular events, including heart attacks and stroke. In addition, niacin can cause unpleasant and potentially dangerous side effects. Therefore, its use has been declining. Niacin/statin combinations include simvastatin/niacin (Simcor) and lovastatin/niacin (Advicor).

Bile-Acid Binding Drugs

Bile-acid binding drugs are also known as bile acid resins or bile acid sequestrants. They reduce LDL levels. Brands include cholestyramine (generic), colesevelam (Welchol), and colestipol (Colestid, generic).

Bile acid resins commonly cause constipation, heartburn, gas, and other gastrointestinal problems, side effects that many people cannot tolerate. These drugs may increase the risk for osteoporosis, elevate triglyceride levels, and interfere with the absorption of other medications.

Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe (Zetia) blocks absorption of cholesterol that comes from food. It helps reduce LDL cholesterol and is often used together with statins. Ezetimibe is used in people with cardiovascular disease who are at very high risk, if high-intensity statin therapy does not lower LDL-cholesterol enough by itself. Ezetimibe can also be used in patients without cardiovascular disease but with very high LDL-cholesterol that is not lowered enough with statins alone.

Vytorin is a combination of ezetimibe and the statin simvastatin in a single pill. Liptruzet combines ezetimibe and the statin atorvastatin in a single pill.

Prescription Fish Oil Supplements

Lovaza and Vascepa are prescription forms of omega-3 fish oil, which may be prescribed to help lower triglyceride in people who have very high levels. Recent research has questioned the benefits of fish oil supplements for preventing heart attack and stroke.

Other Drugs

Mipomersen (Kynamro) and lomitapide (Juxtapid) are approved specifically for treatment of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, a very rare genetic condition that can cause heart attack and stroke before the age of 30.

Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors

A new group of drugs that inhibit a certain enzyme have been released. These drugs not only are able to reduce LDL cholesterol by 60% to 70%, but also appear to reduce the rate of heart attack, death from heart disease, and mortality in all causes.

Two drugs have been approved by the FDA -- evolocumab (Repatha) and alirocumab (Praluent). They are a type of drug called monoclonal antibodies. These drugs are quite expensive. Their exact role in the treatment of elevated LDL cholesterol levels remains to be fully determined. They are used for people with inherited cholesterol disorders and those who are unable to take statin drugs. PCSK9 inhibitors are also recommended in people with very high risk or with very high LDL-cholesterol for whom high-intensity statin treatment does not lower LDL-cholesterol levels enough.

Resources

- American College of Cardiology -- www.acc.org

- American Heart Association -- www.heart.org

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute -- www.nhlbi.nih.gov

References

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. PMID: 30879355 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30879355/.

Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):2969-2989 PMID: 22962670 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22962670/.

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2387-2397. PMID: 26039521 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26039521/.

Chamberlain JJ, Rhinehart AS, Shaefer CF Jr, Neuman A. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(8):542-552. PMID: 26928912 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26928912/.

Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2960-2984. PMID: 24239922 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239922/.

Gallego-Colon E, Daum A, Yosefy C. Statins and PCSK9 inhibitors: A new lipid-lowering therapy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;878:173114. PMID: 32302598 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32302598/.

Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, et al. Update on prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in light of recent evidence: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Circulation. 2015;132(8):691-718. PMID: 26246173 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26246173/.

Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935-2959. PMID: 24239921 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239921/.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;pii: S0735-1097(18)39034-X. PMID: 30423393 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30423393/.

Hartley L, May MD, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, Rees K. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD011472. PMID: 26758499 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26758499/.

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985-3023. PMID: 24239920 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239920/.

Lee JW, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Grapefruit Juice and Statins. Am J Med. 2016;129(1):26-29. PMID: 26299317 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26299317/.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American Heart Association's strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613. PMID: 20089546 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20089546/.

McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD003160. PMID: 26727124 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26727124/.

Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(20):2292-2333. PMID: 21502576 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21502576/.

Mozaffarian D. Nutrition and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 49.

Navarese EP, Robinson JG, Kowalewski M, et al. Association between baseline LDL-C level and total and cardiovascular mortality after LDL-C lowering: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1566-1579. PMID: 29677301 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29677301/.

Nordestgaard BG, Varbo A. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384(9943):626-635. PMID: 25131982 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25131982/.

Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D'Agostino RB Sr, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1422-1431. PMID: 24645848 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24645848/.

Ridker PM, Libby P, Buring JE. Risk markers and the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 45.

Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1489-1499.PMID: 25773378 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25773378/.

Strandberg TE, Kolehmainen L, Vuorio A. Evaluation and treatment of older patients with hypercholesterolemia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014; 312(11):1136-1144. PMID: 25226479 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25226479/.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement. Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Preventive Medication. November 13, 2016. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication. Accessed 12/23/2020.

|

Review Date:

12/23/2020 Reviewed By: Michael A. Chen, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington Medical School, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.