Recently I came across a story that, when I first read it, sounded like an April Fool’s joke. But it’s no joke -- this was published in Nature, one of the most respected scientific journals. Here’s how it goes. In Pakistan, French scientist Roberto Macchiarelli and his team were poking around an ancient burial site -- 9,000 years old, in fact -- when they made a startling discovery. Buried in the long-forgotten graves were the remains of various jaws and teeth whose original owners, apparently, had "been to the dentist."

What's that you say? There was no such thing as a dentist 9,000 years ago? That's what I thought. Well, it turns out these clever Neolithic farmers were doing some pretty advanced procedures to treat cavities. In fact, the teeth contained tiny, precise drill holes in areas that showed evidence of serious tooth decay. (Remember, Crest wasn't invented yet, so we can assume cavities were a common problem.)

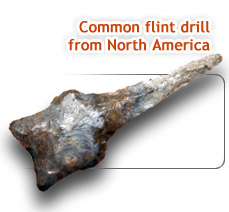

The technique apparently used a high-speed flint drill powered by a bow and thread. Here is a picture of the ancient drill, and a modern drill for a little "then and now" comparison. Dang, we haven’t come very far in 9,000 years!

The wear patterns on the teeth show that the holes were drilled in living patients. (I cringe thinking about it.) This ancient dental drilling practice continued for well over 1,000 years. That means this wasn't an isolated experiment; this was a skill handed down from one dentist to another for a millennium.

When I first heard about this find, it conjured up images of those improbable and goofy inventions on The Flintstones.

Did people whose technology consisted of flat stone scrapers and spear points really have a tiny flint drill in a stick that rotated with thread -- 9,000 years ago? And what could have spurred such brilliant stone-age innovation?

Only one thing -- pain.

You have to wonder what it was like having a toothache in the year 7,000 BC. Travel back with me and speculate. You've got a backbreaking day of work ahead of you -- first you have to chop down a bunch of trees with a primitive axe through brute force, clear it out, then break up the earth with a stone hoe so you can plant your crops. And while you slog through all this work, you've got an intense throbbing pain in your tooth. Your cheek is swollen and your forehead is burning hot. You're hungry, you’re thirsty, and you can't concentrate on the day's work. And there isn't a thing you can do about it -- no aspirin, no pain medicine, no dentist, not even a stiff drink. Nada.

It must have been unbearable. You're almost ready to grab a rock and knock the tooth right out of your jaw. Maybe some other farmer tried that once, and the pain left him even worse off.

In desperation, a thought occurs to you ... maybe a spear point could be made really long and thin… and maybe you could dig the pain out.

In fact, flint drills HAVE been found all over the world, including throughout the United States. They are common here in the woods in Georgia, near the Synergy offices. They were probably used as punches to make holes in deerskin, and the like.

In the case of the Pakistani proto-dentists, they may have learned to drill tiny precise holes when they created beads and other decorative items.

In bygone cultures, flint was worked into tools (such as arrowheads, drills, and scrapers) through a pretty difficult percussion technique of knocking off precise flakes one at a time. It's definitely not a trivial skill, but many ancient groups had mastered it, so perhaps it wasn't such a big deal to modify bead drills and turn them into the first tiny dental drill. The scientists found flint drill heads at the site, so it’s a good guess that the drills made the holes in the teeth.

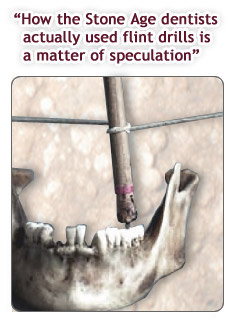

On the other hand, how the Stone Age dentists actually used the flint drills is a matter of more speculation. The researchers were able to replicate the holes using a bow and arrow contraption.

I'm guessing the Stone Age dentists found it difficult to get their fingers into the back of the mouth to rotate their drill. So they put the drill at the end of a stick, like a spear point, and poked the stick into the mouth at an angle. Then some Neolithic Einstein figured out that you could wrap a bow string around the stick at a right angle, and crank it to make the drill dig deep. (I do think this was on an episode of The Flintstones.)

Now imagine what it was like getting that treatment without Lidocaine. (It may have helped to smash a couple of rocks together while you screamed.) During interviews, the scientists speculated that the procedure was unbearably painful. We can only hope the drilling procedure provided some lasting relief to the toothache. One patient had multiple drill holes in his infected teeth.

When I contemplate such things, I am truly thankful for modern medicine. The technique may not have changed much -- we still drill out the rotten parts of our teeth -- but at least we have a way to deaden the nerves. We have to realize that despite the flaws and cost of U.S. healthcare, we still have it pretty good these days.

Reference:Coppa A, Bondioli L, Cucina A, et al. Palaeontology: Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry. Nature. April 6, 2006: 440; 755-756. Accessed online at www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7085/abs/440755a.html

|