Coronary artery disease - InDepth

Highlights

Coronary Artery Disease

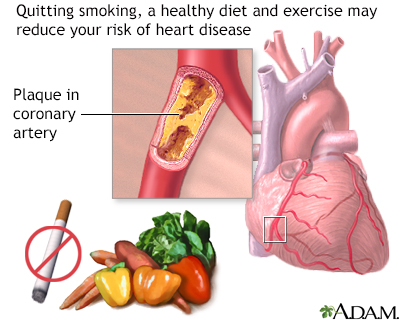

Coronary artery disease (CAD), also called coronary heart disease, is a condition in which fatty deposits, called plaque, build up in the heart's arteries. These deposits cause arteries to become narrow and blocked, which restricts oxygen rich blood flow to the heart muscle. CAD is the leading cause of death for both men and women in the United States.

Risk Factors

The most important factors that increase the risk for CAD are:

- Smoking

- Unhealthy cholesterol and lipid levels

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Lack of exercise

- Obesity

- Advancing age

- Family history of early heart disease

Symptoms

Angina is the primary symptom of CAD. Angina feels like gripping pain or pressure in the chest area.

- Stable angina is predictable chest pain that lasts a few minutes or less and is usually relieved by rest or medication. It is often triggered by a similar degree of physical exertion or emotional stress.

- Unstable angina is unpredictable chest pain and may occur at rest. When patients with stable angina have symptoms that are more severe or occur with less and less activity it is called unstable angina. It is a more serious condition than stable angina and can be a warning sign of a heart attack.

Some people with CAD have few or no symptoms. Often a heart attack or an episode of unstable angina is the first sign that a person has CAD.

Treatment

Lifestyle changes (such as a healthy diet and regular physical activity) are essential for preventing and treating CAD.

Medications for preventing and treating CAD include aspirin and related drugs, cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins), and high blood pressure medications (such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors). Some patients take nitrate drugs such as nitroglycerin or other medications (including some blood pressure medications) to treat angina.

Procedures may be needed to open a blocked or narrowed coronary artery and improve blood flow to the heart. These approaches are known as revascularization therapy. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also called angioplasty (usually with stenting), uses a small balloon to open the blood vessel. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) is a more invasive procedure that is generally recommended for patients with multiple severe blockages or underlying diseases such as diabetes or reduced heart pumping power. It uses grafts in the form of arteries or veins to reroute blood flow around blockages to the heart muscle.

Heart Disease Guidelines

The American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and other professional organizations' guidelines recommend:

- For people with heart disease, controlling blood pressure and lipids is very important, as is the daily use of antiplatelet therapy (usually aspirin).

- People deciding between CABG and PCI should meet with an interdisciplinary medical team that includes both a cardiac surgeon and an interventional cardiologist. CABG is a more invasive procedure. But it may work better than PCI for certain people, depending on the location and number of blockages as well as other factors such as how well the heart is functioning and other medical problems the person might have, such as diabetes.

- Cardiac rehabilitation is strongly recommended, especially for people who have undergone bypass surgery. People with heart disease should also be screened for depression.

- Sexual activity is safe for most people with stable CAD after consultation with your health provider. But people with severe heart disease should usually abstain until their condition stabilizes.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD), also called heart disease or ischemic heart disease, results from a complex process known as atherosclerosis.

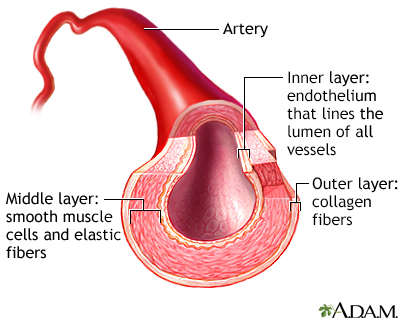

Atherosclerosis is the hardening and narrowing of the arteries caused by the build-up of plaque inside the walls of the arteries. (Plaque is the sticky substance made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances found in the blood.) Examples of cardiovascular diseases caused by atherosclerosis include CAD, heart attack, peripheral artery disease (PAD), and stroke.

In atherosclerosis, fatty deposits (plaques) of cholesterol and other cellular waste products together with inflammatory cells build up in the inner linings of the heart's arteries. This causes the blockage of arteries and prevents oxygen-rich blood from reaching the heart (ischemia). There are many steps in the process leading to atherosclerosis, some not yet fully understood.

Cholesterol and Lipoproteins

The atherosclerosis process begins with cholesterol and sphere-shaped bodies called lipoproteins that transport cholesterol.

- Cholesterol is a substance found in all animal cells and animal-based foods. It is critical for many functions. But under certain conditions cholesterol can be harmful.

- The lipoproteins that transport cholesterol are referred to by their size. The most commonly known lipoproteins are low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and high density lipoproteins (HDL). LDL is often referred to as "bad" cholesterol. HDL is often called "good" cholesterol.

- Triglycerides are another type of lipid (fat) that lipoproteins help circulate through the blood. High levels of triglycerides, like high levels of LDL, can increase the risk for heart disease.

Oxidation

A damaging process called oxidation is an important trigger of atherosclerosis.

- Oxidation is a chemical process in the body caused by the release of unstable particles known as free radicals. It is one of the normal processes in the body. But under certain conditions (such as exposure to cigarette smoke or other environmental stresses) these free radicals are overproduced.

- In excess amounts, free radicals can be very dangerous, causing damaging inflammation and even affecting genetic material in cells.

- In heart disease, free radicals are released in artery linings where they oxidize LDL. The oxidized LDL is the basis for cholesterol build-up and damage on the artery walls, leading to heart disease.

Inflammatory Response

For the arteries to harden there must be a persistent reaction in the body that causes ongoing harm. This reaction is an immune process known as the inflammatory response.

Blockage in the Arteries

Eventually, the plaque buildup causes arteries to become narrower, a condition known as stenosis.

- As this narrowing and hardening process continues, blood flow slows, preventing sufficient oxygen-rich blood from reaching the heart muscles. The supply can fall short of the demands of working muscle.

- This oxygen deprivation is called ischemia. When it is severe enough in the coronary arteries, it causes injury to the tissues of the heart.

- These narrow and stiff arteries not only slow down blood flow. They also become vulnerable to injury and clot formation, which is what usually triggers a heart attack.

The End Result: Heart Attack

A heart attack can result in several ways from atherosclerosis:

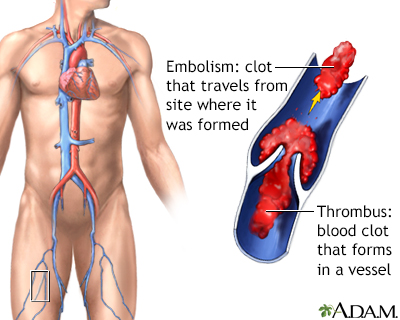

- Type 1 heart attack occurs when the plaque develops a fissure or tears. Blood platelets stick to the tears to seal off the plaque, and a blood clot (thrombus) forms. A heart attack can then occur if the blood clot severely or completely blocks blood flow to the heart muscle.

- Type 2 heart attack develops from a problem with oxygen supply and demand. A heart attack can occur if the heart's oxygen demand increases to exceed the (sometimes already narrowed) artery's ability to deliver oxygen-rich blood.

Risk Factors

CAD, also called coronary heart disease or ischemic heart disease, is the leading cause of death in the United States. Over the past few decades, heart disease rates declined in both men and women as more people quit smoking and improved their dietary habits. However, this improvement has leveled off in recent years, most likely because of the dramatic increase in obesity.

Age

The risk of CAD increases with age. Most people who die from heart disease are over the age of 65. However, many people younger than this are also at risk.

Women who reach menopause before the age of 35 have a significant increase in risk for heart disease as they age. This increase is primarily due to a rise in levels of LDL (bad) cholesterol and triglycerides, and a decrease in levels of HDL (good) cholesterol

Sex

Men have a greater risk for CAD and are more likely to have heart attacks earlier in life than women. After age 60, women's risk of dying from heart disease is very close to that of men. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in both women and men.

Women with a history of angina, heart attack, or other heart or circulation problems are generally advised not to take hormone therapy when reaching menopause.

Genetic Factors and Family History

Heart disease tends to run in families. People whose parents or siblings developed heart disease at a younger age are more likely to develop it themselves. This is in part due to certain genetic factors which increase the likelihood of developing risk factors, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, but other factors likely play a role as well.

Race and Ethnicity

African Americans have the highest risk of heart disease, due in part due to higher rates of severe high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking is the most important lifestyle risk factor for heart disease. Smoking can cause elevated blood pressure, worsen lipid levels, and make platelets very sticky, raising the risk of clots. Although heavy cigarette smokers are at greatest risk, people who smoke as few as three cigarettes a day are at increased risk for blood vessel abnormalities that endanger the heart. Regular exposure to secondhand smoke also increases the risk of heart disease in nonsmokers.

Alcohol

Moderate alcohol consumption (less than one or two drinks a day for men, less than one drink a day for women; one drink is 5 ounces or 150 mL wine, 12 ounces or 360 mL beer, or 1.5 ounces or 45 mL hard liquor at 80 proof) may be associated with higher HDL "good" cholesterol levels. The relationship between alcohol and heart disease is complex and not clear. Heavy drinking harms the heart. A healthcare provider can provide a detailed review of what is known about the risks and benefits of alcohol consumption.

An unhealthy diet can increase the risk for heart disease. Examples include foods rich in trans-fats and cholesterol, or containing high amounts of salt and added sugars. A healthy diet plays an important role in maintaining the health of the heart, especially by controlling dietary sources of cholesterol and restricting salt intake that contributes to high blood pressure.

Physical Inactivity

Exercise has a number of effects that benefit the heart and circulation, including improving cholesterol and lipids, lowering blood pressure and blood sugar levels, and improving weight control. People who are sedentary are almost twice as likely to suffer heart attacks as are people who exercise regularly.

Medical Conditions

Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Excess body fat, especially around the waist, is a significant risk factor for heart disease. Obesity also increases the risk for other conditions (such as high blood pressure and diabetes) that are associated with heart disease. Obesity is particularly hazardous when it is part of the metabolic syndrome, a pre-diabetic condition that is significantly associated with heart disease. This syndrome is diagnosed when at least three of the following are present:

- Abdominal obesity (fat around the waist)

- Low HDL (good) cholesterol

- High triglyceride levels

- High blood pressure

- Insulin resistance (diabetes or prediabetes)

There are numerous ways to control your weight and diet can help. People may be advised to adhere to the Mediterranean diet to improve aspects of the metabolic syndrome. This diet emphasizes eating fruits and vegetables, whole grains, beans and nuts, using olive and canola oil instead of butter, and herbs and spices instead of salt, limiting red meat consumption.

Unhealthy Cholesterol and Lipid Levels

LDL cholesterol is the "bad" cholesterol responsible for many heart problems. Triglycerides are another type of lipid (fat molecule) that can be bad for the heart when there are high levels. HDL cholesterol is the "good" cholesterol that helps protect against heart disease. Doctors test for a lipid profile that includes measurements for total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides. The ratio of these lipids can affect heart disease risk.

High blood pressure (hypertension) is associated with coronary artery disease and heart attack. For an adult, a normal blood pressure reading is below 120/80 mm Hg. Blood pressure readings 120 to 129 systolic (but diastolic <80 mmHg) are referred to as "elevated blood pressure" and "hypertension" is diagnosed for established blood pressure reading greater than or equal to 130 mm Hg (systolic) or greater than or equal to 80 mm Hg (diastolic).

Diabetes

Diabetes, especially for people whose blood sugar levels are not well controlled, significantly increases the risk of developing heart disease. In fact, heart disease and stroke are the leading causes of death in people with diabetes. People with diabetes, both type 1 (so-called "juvenile") and type 2 (so-called "adult onset") are also at risk for high blood pressure and unhealthy cholesterol levels, blood clotting problems, and impaired nerve function, all of which can damage the heart.

Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD)

PAD occurs when atherosclerosis affects the extremities, particularly the feet and legs. The major risk factors for heart disease and stroke are also the most important risk factors for PAD. (The combination of such conditions with PAD also produces more severe forms of heart or circulatory disease.) Even though signs of heart disease are often not evident in many people with PAD, most of these people also have CAD.

Depression

Although people with heart disease may become depressed, this does not explain entirely the link between the two problems. Data suggest that depression itself may be a risk factor for heart disease as well as its increased severity. A number of studies indicate that depression has biological effects on the heart, including blood clotting and heart rate. Guidelines recommend that patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery or angioplasty (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]) be screened for depression. Stress may also contribute to risk.

Risk Factors with Unclear Roles

Homocysteine and Vitamin B Deficiencies

Deficiencies in the B vitamins folate (known also as folic acid), B6, and B12 have been associated with a higher risk for heart disease in some studies. Such deficiencies produce higher blood levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that has been associated with a higher risk for heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.

However, while B vitamin supplements do help lower homocysteine levels, they appear to have no effect on heart disease outcomes, including preventing heart attack or stroke. Research indicates that homocysteine may be a marker for heart disease rather than a cause of it.

In general, there is little evidence supporting vitamin supplements for heart disease prevention. According to the United States Preventive Services Task Force, there is insufficient evidence that regular use of multivitamin supplements reduces the risk for heart disease. There is conclusive evidence that beta-carotene and vitamin E supplements do not help protect against heart disease.

C-Reactive Protein

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a product of the inflammatory process. High levels of CRP may be associated with a higher risk for atherosclerosis. However, it is not known if the protein plays any causal role or whether it is simply a marker for other factors in the disease process.

Lp(a)

Lipoprotein-a, also called Lp(a) is a lipoprotein that is associated with CAD and stroke.

LP PLA2

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (LP-PLA2) is a marker of vascular inflammation which is associated with heart disease and stroke.

Apolipoprotein B (apoB or apoB 100)

Apolipoprotein B is a component of lipoproteins like LDL and is associated with cardiovascular disease risk.

C pneumoniae and Other Infectious Organisms

Some microorganisms and viruses may possibly contribute to the inflammation and damage in arteries. The most interesting evidence to date suggests a potential role for Chlamydia (C) pneumoniae (an atypical bacterial organism that causes mild pneumonia in young adults). C pneumoniae is sometimes detected in plaques in the arteries of people with heart disease. However, treatment with appropriate antibiotics has not been found to reduce the risk of future heart problems for people infected with this organism.

Other studies suggest that cytomegalovirus (CMV), a common virus, may have similar effects. However, many people have been infected with these organisms, and no clear association has been found with any of these infections.

Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder. It occurs when tissues in the upper airways come too close to each other during sleep, temporarily blocking the inflow of air. There is evidence that severe OSA is an independent risk factor that may cause or worsen a number of heart-related conditions. People with severe, untreated OSA are at increased risk for CAD, high blood pressure, stroke, and heart attack.

Periodontal Disease

Periodontal disease and heart disease are both inflammatory conditions that share common risk factors such as smoking and diabetes. According to the American Heart Association, more evidence is needed to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between gum disease and heart disease. Still, periodontists and cardiologists recommend that people who have periodontal disease and at least one risk factor for heart disease should have a medical evaluation for heart problems. People who have CAD should have regular exams to check for signs of periodontal disease.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of CAD include:

- Angina (chest pain)

- Shortness of breath (particularly during physical exertion)

- Rapid heartbeat

Sometimes patients with CAD have few or no symptoms until they have heart attack or heart failure.

Angina

Angina is a symptom, not a disease. It is the primary symptom of CAD and, in severe cases, of a heart attack. It is typically felt as chest pain and occurs as a consequence of a condition called myocardial ischemia. Ischemia results when the heart muscle does not get as much blood and oxygen as it needs for a given level of work. Angina is usually referred to as one of two states:

- Stable Angina, which is predictable.

- Unstable Angina, which is new, less predictable, and a sign of a more serious condition.

Angina can be mild, moderate, or severe. The intensity of the pain does not always relate to the severity of the medical problem. Some people might feel a crushing pain from mild ischemia. Others might feel only mild discomfort from severe ischemia. Some people do not have symptoms and they are diagnosed as having "silent ischemia".

Stable Angina and Chest Pain

Stable Angina

Stable angina is predictable chest pain. Although less serious than unstable angina, it can be extremely painful or uncomfortable. It is usually relieved by rest and responds to medical treatment (typically nitroglycerin). Any event that increases oxygen demand can cause an angina attack. Some typical triggers include:

- Exercise

- Cold weather

- Emotional upset

- Large meals

Angina attacks can happen at any time during the day. But more occur between 6 a.m. and 12 p.m.

- Angina pain or discomfort is typically described by people as fullness, tingling, squeezing, pressure, heavy, suffocating, or gripping. It is rarely described as stabbing or burning. Changing one's position or breathing in and out does not affect the pain.

- A typical angina attack lasts several minutes. If it is more fleeting or lasts for hours, it is probably not angina.

- The pain is usually in the chest, under the breastbone. It often radiates to the neck, jaw, or left shoulder and arm. Less commonly, people report symptoms that radiate to the right arm or back, or even to the upper abdomen.

- Women, older people, and people with diabetes are particularly likely to experience atypical symptoms that often involve discomfort in the abdomen, nausea, or unusual fatigue and weakness instead of chest pain.

- Stable angina is usually predictably relieved by rest or by taking nitroglycerin under the tongue.

Other symptoms that may indicate angina or accompany the pain or pressure in the chest include:

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea, vomiting, and cold sweats

- A feeling of indigestion or heartburn

- Unexplained fatigue (more common in women)

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Palpitations

Unstable Angina and Acute Coronary Syndrome

Unstable angina is a serious situation and is often an intermediate stage between stable angina and a heart attack, in which an artery leading to the heart muscle (a coronary artery) becomes sufficiently blocked so that the blood supply to the heart drops and the heart muscle dies. A person is usually diagnosed with unstable angina under one or more of the following conditions:

- Pain awakens a person or occurs during rest.

- A person who has never experienced angina has severe or moderate pain during mild exertion (walking two level blocks or climbing one flight of stairs).

- Stable angina has progressed in severity or occurs with less provocation, and medications are less effective in relieving its pain.

- The person suffers a fainting episode, usually while or after having some of these other symptoms.

- Overall worsening of angina burden.

Unstable angina is usually discussed as part of a set of conditions called acute coronary syndromes (ACS). ACS also includes a condition called non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) -- also referred to as non-Q wave myocardial infarction. With NSTEMI, blood tests indicate a heart attack. The third type of ACS is ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), during which one of the major heart arteries is completely blocked and full-thickness heart muscle damage may occur.

Other Types of Angina

Prinzmetal's Angina

This type of angina is caused by a spasm of a coronary artery. It generally has no relationship to activity. Irregular heartbeats are common. But the pain is generally relieved promptly with standard treatment (nitrate medicines or calcium-channel blockers).

Silent Ischemia

Some people with severe CAD do not have angina pain. This condition is known as silent ischemia, which may occur when the brain abnormally processes heart pain. Silent ischemia is a dangerous condition because patients have no warning signs of heart disease. Some studies suggest that people with silent ischemia have higher complication and mortality rates than those with angina pain.

Other Causes of Chest Pain or Discomfort

Chest pain is a very common symptom in the emergency room. But heart problems account for less than half of all chest pain episodes. There are many other causes of chest pain or discomfort, including:

- Injured muscles

- Inflamed joints, such as those between the breastbone and ribs (costochondritis)

- Arthritis

- Heartburn and GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease)

- Asthma and other lung problems

- Problems with the aorta or other blood vessels

Still, if you are experiencing chest pain, it is best to seek immediate medical attention.

Diagnosis

Many tests are used to diagnose heart disease. The choices of which and how many tests to perform depend on the person's risk factors, history of heart problems, and current symptoms. Usually, the tests begin with the simplest and may progress to more complicated ones.

Routine Tests to Determine Risk for Heart Disease

Doctors routinely check for high blood pressure and unhealthy cholesterol levels in all older adults. In some cases, the doctor may test for levels of CRP, which is associated with increased inflammation in the body.

Other tests may also be ordered such as blood tests for Lp(a) and LP-PLA2, or imaging tests (coronary calcium or carotid intima-medial thickness measurement). Specific tests are also important in people who may have risk factors or symptoms of diabetes.

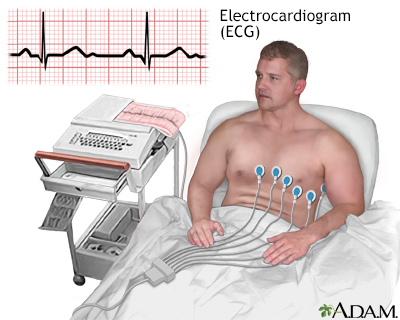

Electrocardiograms (ECGs)

An electrocardiogram (ECG) measures and records the electrical activity of the heart. However, up to half of people who suffer from angina or silent ischemia have normal ECG readings. The waves measured by the ECG correspond to when different parts of the heart contract and relax. Specific waves seen on an ECG are named with letters:

The electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG) is used extensively in the diagnosis of heart disease, from congenital heart disease in infants to myocardial infarction and arrhythmias in people of all ages. There are several different portions of an electrocardiogram.

- P. The P wave is associated with the contractions of the atria (the two chambers that receive blood from outside the heart).

- QRS. The QRS is a series of waves associated with ventricular contractions. (The ventricles are the two major pumping chambers in the heart.)

- T and U. These waves follow the ventricular contractions.

The most important wave patterns in diagnosing and determining treatment for heart disease and heart attack are ST deviations, T-wave abnormalities, and Q waves:

- A depressed ST segment or a T-wave inversion (upside down) suggests some blockage and may indicate the presence of heart disease, even if there is no angina present.

- ST elevations and Q waves are the most important wave patterns in diagnosing and determining treatment for a heart attack. They suggest that an artery to the heart is completely blocked and that the full thickness of the heart muscle is at risk. However, ST segment elevations alone do not always mean the person has a heart attack. Other factors are important in making a diagnosis.

Exercise Stress Test

Exercise stress test for evaluation of CAD may be performed in the following situations:

- People with possible or probable angina, to help determine the likelihood of CAD being present.

- People who were previously stable who suddenly began having symptoms.

- Follow-up of people with known heart disease or following coronary bypass surgery or a percutaneous intervention.

- To determine how well the heart can respond when extra demand is needed.

- People with certain types of heart rhythm disturbances.

- After a heart attack, either before leaving the hospital or soon afterward.

Basic Procedure

A stress test (exercise tolerance test) monitors heart rhythms and other parts of the ECG, especially the ST segment, blood pressure, and clinical status. It can tell how well the heart handles work and if parts of the heart have decreased blood supply. A typical stress test involves:

- The person walks on a treadmill or rides a stationary bicycle. Exercise continues until the heart is beating at least 85% of its maximum rate, until symptoms of heart trouble occur (changes in blood pressure, heart rhythm abnormalities, angina, and fatigue), or the person simply wants to stop.

- For people who cannot exercise, the doctor may administer dobutamine, which is a drug that simulates the stress of exercise or other drugs that dilate arteries. In these types of tests, some form of imaging is required.

An ECG is used to monitor heart rhythms during a stress test. (An echocardiogram or more advanced imaging technique may also be used to visualize the actions of the heart and blood flow.)

Interpreting Results

To accurately assess heart problems, varieties of factors are measured or monitored using the ECG and other tools during exercise. They include:

- Exercise capacity. This is a measure of a person's capacity to reach certain metabolic rates.

- ST waves on the ECG. Doctors specifically look for abnormalities in part of the wave tracing called an ST segment. A certain type of ST segment depression may suggest the presence of heart disease. However, sex, drugs, and other medical conditions can affect the ST segment.

- Heart rate. This is how fast the heart rate goes during exercise and how quickly it returns to normal recovery. Based on age and other factors, everyone's heart rate should go up to a certain level during exercise. If it does not go up to the expected level or stays high too long after stopping exercise, the person is considered at risk for heart problems.

- Changes in systolic blood pressure. Generally, the blood pressure will go up during exercise. If blood pressure drops or rises quickly this can be a sign of other problems.

- Oxygen levels may also be measured.

Using these and other measures, doctors can determine risk fairly accurately, particularly for men with chronic stable angina. However, the test has limitations, and some are significant. In people with suspected unstable angina, normal or low risk results may not be as accurate in predicting future risk of cardiac events.

Depending on the type of test and the population studied (young people or those with few risk factors and atypical symptoms) a significant proportion of people will have false positive test results. In such cases, test results indicate abnormalities when there are no heart problems.

Echocardiograms

An echocardiogram is a noninvasive test that uses ultrasound images of the heart. This test is more expensive than an ECG-only stress test. But it can provide very valuable information, particularly in identifying whether there is damage to the heart muscle and the extent of heart muscle damage. An echocardiogram also provides other information about heart structure and function, such as the valves.

A stress echocardiogram may be performed to further evaluate abnormal findings from an exercise treadmill test or a routine echocardiogram. Examples include identifying exactly which part of the heart may be involved and quantifying how much muscle has been affected. It may be the first test done when a standard exercise treadmill test cannot be performed.

Radionuclide Imaging

Radionuclide procedures use imaging techniques and computer analyses to plot and detect the passage of radioactive tracers through the heart. Such tracing elements are given intravenously. Radionuclide imaging is useful for diagnosing and determining:

- Severity of unstable angina when less expensive diagnostic approaches are unavailable or unreliable.

- Severity of chronic CAD.

- Success of revascularization procedures for CAD.

- Whether a heart attack has occurred.

Myocardial Perfusion (Blood Flow) Imaging Test (also called the Thallium Stress Test)

This radionuclide test is typically used with an exercise or chemical stress test to determine blood flow to the heart muscles. It is a reliable measure of severe heart events. It may be useful in determining the need for angiography.

First, a radioactive tracer (such as thallium, technetium, or sestamibi) is given through an IV while the person is at rest. Then, a scan of the heart is done. Sometime after this exercise/stress is begun, and about a minute before the person is ready to stop exercising, the doctor administers a radioactive tracer into the intravenous line. Immediately afterward, the person lies down for a second heart scan.

The images before and after exercise are compared to look for areas that appear to be getting less blood flow during stress. Sometimes delayed imaging is performed to see if areas of the heart may benefit from revascularization in an area of a prior heart attack.

Radionuclide Angiography

This test is a technique for evaluating the main pumping chambers of the heart (the ventricles). It uses an injected radioactive tracer and can be performed during exercise, at rest, or with use of stress-inducing drugs. It can help determine the function of the ventricles (left more commonly than the right) and is an alternative to echocardiograms in certain situations.

Angiography

Angiography is an invasive test. It is used for people who show strong evidence for severe obstruction on stress and other tests, for people with severe typical symptoms, and for people with ACS. It is required when there is a need to know the exact anatomy and disease present within the coronary arteries and is often followed by PCI, also called angioplasty and stenting.

In an angiography procedure:

- A narrow tube is inserted into an artery, usually in the leg or arm, and then threaded up through the body to the coronary arteries.

- A dye is injected into the tube, and an x-ray records the flow of dye through the arteries.

- This process provides a map of the coronary circulation, revealing any blocked areas.

- Once these blocked areas have been identified, PCI is sometimes performed.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is a noninvasive imaging technique that can provide three-dimensional images of the heart and major blood vessels leading to and away from the heart.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scans may be used to evaluate CAD as well as other aspects of heart structure.

Calcium Scoring CT Scans of the Heart

These scans are used to detect calcium deposits on the arterial walls. The presence of calcium correlates well with the presence of atherosclerosis of the heart. If the calcium score is very low, a person is unlikely to have CAD. A higher calcium score may indicate an increased risk of current and future CAD. However, the presence of calcium does not necessarily signify narrowing of the arteries that would need further immediate evaluation or treatment. Using this test as a screening tool to identify people in the general population for increased risk of heart disease is generally not recommended.

CT Angiography

CT scans may also be used to visualize the coronary arteries. When compared to invasive angiography, CT angiography is not as accurate in identifying who has significant CAD and who does not. However, when a patient's CT angiogram is completely normal, it is very unlikely that they have significant blockages. CT techniques include electron beam computed tomography (EBCT) and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT), which use different technologies to generate images of the heart. The optimal way to use these tests has yet to be determined.

Prevention

Heart disease prevention is important before and after someone is diagnosed with the condition:

- Primary prevention. Refers to measures that everyone should take to reduce their risk of heart disease.

- Secondary prevention. Refers to measures that a patient, already diagnosed with heart disease, should take to reduce the risk of having additional heart damage or complications such as a heart attack. Many of these measures are similar or the same as those recommended for primary prevention.

Key prevention measures include:

- People should stop smoking and avoid exposure to secondhand smoke.

- Maintain cholesterol levels at appropriate levels using a heart healthy diet, exercise, and statin medications.

- Maintain an appropriate low blood pressure level using diet and medications.

- Maintain an active lifestyle.

- Maintain a healthy body weight.

- Use an antiplatelet drug such as aspirin or clopidogrel, if appropriate.

- Manage diabetes and kidney disease when present.

- Receive an annual influenza vaccination.

Smoking Cessation

Your doctor should ask about your smoking habits at every visit. Smoking is a chronic condition and often requires repeat therapy using more than one technique.

Control Cholesterol

People should start following a heart-healthy diet and exercise regularly, after talking to their doctors.

Healthy diet, regular exercise, and quitting smoking (if you smoke) may prevent heart disease. Follow your health care provider's recommendations for treatment and prevention of heart disease.

When deciding on whether to use statin medications, newer guidelines for cholesterol treatment focus on a person's overall risk for cardiovascular disease and treating with appropriately potent medications geared to the person's risk-level, rather than aiming for a target cholesterol number. Statin drugs are the recommended treatment for lowering LDL (bad) cholesterol levels in people when lifestyle changes have failed. Statins are recommended:

- For people with known cardiovascular disease.

- For people with diabetes.

- For people with genetic disorders causing elevated LDL cholesterol levels.

- When a number of risk factors including cholesterol blood level, are considered, using what is called a risk calculator. If you are between the ages of 40 and 75 and a risk calculator indicates your risk for heart disease in the next 10 years is at or above 7.5% to 10%, statins are recommended.

Manage High Blood Pressure

According to the AHA/ACC 2017 blood pressure guidelines, people in normal health should have a blood pressure reading of less than 120/80 mm Hg is considered normal, readings of 130/80 mm Hg or higher indicates high blood pressure (hypertension), and readings in between the two are called elevated blood pressure. Stage 1 hypertension refers to people whose blood pressure is between 130 to 139/80 to 90 mm Hg and Stage 2 for people at least 140 / at least 90 mm Hg. People whose blood pressures stay above 130/80 mm Hg despite lifestyle therapy (diet, exercise, and weight control) should be treated with blood pressure medications.

If you have heart problems, diabetes, kidney problems, or a history of a stroke, medicines may be started at lower blood pressure reading. The most commonly used blood pressure targets for people with these medical problems are below 130/80 mm Hg.

Manage Diabetes

People with diabetes should have their blood sugar (glucose) levels well managed. For most people, a goal would be to bring HbA1c levels down to around 7%. In general, people with diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) should aim for blood pressure levels of less than 130/80 mm Hg (systolic/diastolic). For some people, especially younger people, a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 130 mm Hg may be appropriate. People with diabetes and stable heart disease should not take the diabetes drug rosiglitazone (Avandia) because it may increase the risk for heart attack and heart failure.

Heart-Healthy Diet

Current American Heart Association (AHA) for guidelines for a heart-healthy diet recommends:

- Balance calorie intake and physical activity to achieve or maintain a healthy body weight.

- Consume a diet rich in a variety of vegetables and fruits.

- Choose whole-grain, high-fiber foods. These include fruits, vegetables, and legumes (beans). Good whole grain choices include whole wheat, oats/oatmeal, rye, barley, brown rice, buckwheat, bulgur, millet, and quinoa.

- Consume fish, especially oily fish, at least twice a week (about 8 ounces/week or 225 grams/week). Oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, and sardines are rich in the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Consumption of these fatty acids in the form of fish is linked to reduced risk of sudden death and death from CAD.

- Limit daily intake of saturated fat (found mostly in animal products) to less than 7% of total calories, trans fat (found in hydrogenated fats, commercially baked products, and many fast foods) to less than 1% of total calories, and cholesterol (found in eggs, dairy products, meat, poultry, fish, and shellfish) to fewer than 300 mg per day. Choose lean meats and vegetable alternatives (such as soy). Select fat-free and low-fat dairy products. Grill, bake, or broil fish, meat, and skinless poultry.

- Use little or no sodium (salt) in your foods. Reducing sodium can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of heart disease and heart failure.

- Cut down on beverages and foods that contain added sugars (corn syrups, sucrose, glucose, fructose, maltose, dextrose, concentrated fruit juice, and honey).

- If you drink alcohol, do so in moderation. The AHA recommends limiting alcohol to no more than 2 drinks per day for men and 1 drink per day for women.

Weight Reduction

People should aim for a BMI index of 18.5 to 24.9. Weight reduction is recommended for overweight patients who have high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, metabolic syndrome, or diabetes.

Some obese patients with CAD may consider having bariatric surgery (stomach bypass) to lose excess weight. The weight lost after surgery can help improve blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, and other factors associated with CAD.

Exercise

Inactivity is a major risk factor for CAD, on par with smoking, unhealthy cholesterol, and high blood pressure. In fact, studies suggest that people who change their diet in order to control cholesterol only achieve a lower risk for heart disease when they also follow a regular aerobic exercise program. Resistance (weight) training offers a complementary benefit to aerobics exercises.

Even moderate exercise reduces the risk of heart attack and stroke. Current guidelines recommend at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on 5 or more days per week for a total of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous exercise per week.

Your doctor needs to know if your activity causes any angina symptoms. Sudden strenuous exercise (especially snow shoveling or similarly vigorous activities, especially in cold weather) puts many people at risk for angina and heart attack. People with angina should never exercise shortly after eating. People with risk factors for heart disease should seek medical clearance and a detailed exercise prescription. And all people, including healthy individuals, should listen carefully to their bodies for signs of distress as they exercise.

Sexual Activity

Most people with stable CAD can safely engage in sexual activity. People with severe heart disease should abstain from sex until their condition has stabilized. Exercise and cardiac rehabilitation can help lower the risks associated with sexual exertion. Discuss with your doctor how your heart medications may affect your sexual function, and be sure to report to your doctor any symptoms you experience during sex.

PDE5 inhibitor drugs like sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis), avanafil (Stendra) are safe and helpful for most patients with stable CAD who have issues with erectile dysfunction. However, people who take nitrate drugs in any form must never take PDE5 inhibitors. PDE5 inhibitors should be used with caution in men who have recently suffered a heart attack or stroke as well as men with unstable angina.

Influenza Vaccination (Flu Shot)

People with CAD are considered at high risk for complications from influenza. People with CAD should get an annual flu shot.

Treatment

Lifestyle changes (such as weight control, exercise, and quitting smoking) are the primary approach for all degrees of CAD. Depending on severity and individual conditions, people may also need one or more medications, surgery, or a combination of therapies.

Medications

Many types of medications are used to treat angina and CAD. They include:

- Statins

- Antiplatelets and anticoagulants

- Beta blockers

- Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- Nitrates

- Calcium channel blockers

Interventional Procedures and Surgery

Intervention is usually recommended for people who have:

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), such as unstable angina, non-ST elevation MI and ST elevation MI when the procedure is done immediately.

- Recurrent episodes of angina that do not respond to intensive medical therapy and therefore limit patient's lifestyle.

- Severe CAD (severe angina, multi-artery involvement, evidence of ischemia, or significant narrowing of left main coronary artery), particularly if abnormalities are evident in the left ventricle of the heart, the main pumping chamber.

The two main procedures for patients with CAD are:

- Coronary artery bypass grafting (commonly called bypass or CABG), which is usually reserved for patients with severe CAD.

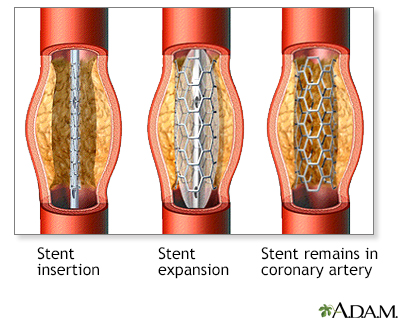

- PCI (commonly called angioplasty), usually with coronary artery stent placement. PCI is less invasive than CABG. But blood vessels can close up again (restenosis) so that people require additional procedures.

The decision to choose angioplasty or coronary artery bypass depends on a person's profile, including the number and types of coronary arteries involved, previous procedures, other health conditions, patient preference, and more. PCI is less invasive than CABG and is more commonly performed. However, CABG may provide better outcomes for certain people, including those with diabetes or heart failure or with blockages in particular locations. Sometimes so-called "hybrid" procedures may be performed where a person gets a combination of surgical bypass and stenting.

People considering surgery should discuss all options and risks with their doctors. Guidelines recommend that people with CAD discuss their treatment options with a medical team that includes both a cardiac surgeon (who performs CABG) and an interventional cardiologist (who performs PCI). No procedure cures CAD or the systemic process underlying it (atherosclerosis), and people must continue to rigorously maintain a healthy lifestyle and any necessary medications. For some people, lifestyle changes and medications may be able to control the disease without surgery or angioplasty.

Medications

Statins

Statins are the first-line drugs for lowering high LDL (bad) cholesterol levels and reducing the risk for heart attack and stroke. Current joint guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend statin therapy for patients with existing atherosclerotic heart disease and people at significant risk for heart disease.

The ACC/AHA has designed a special "risk calculator" to compute cardiovascular disease risk percentage. A doctor enters into the calculator a patient's sex, age, race, total cholesterol, HDL (good) cholesterol, blood pressure, diabetes status, and smoking status. If the formula indicates a 7.5% or higher risk for having a heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years, treatment with a statin drug is recommended.

Statin drugs approved in the United States are lovastatin (Mevacor, generic), pravastatin (Pravachol, generic), simvastatin (Zocor, generic), atorvastatin (Lipitor, generic), fluvastatin (Lescol), pitavastatin (Livalo), and rosuvastatin (Crestor).

Anti-Clotting Drugs

Anti-clotting drugs that inhibit or break up blood clots are used at every stage of heart disease. They are generally classified as either antiplatelets or anticoagulants. Both antiplatelets and anticoagulants prevent blood clots from forming. But they work in different ways. Antiplatelets prevent blood platelets from sticking together. Anticoagulants are "blood thinners" that reduce blood clotting. Both of these therapies carry the risk of bleeding, which can lead to dangerous situations, including stroke.

For most patients with CAD, antiplatelet drugs are preferred over anticoagulants. Anticoagulants are often prescribed for patients with atrial fibrillation or prosthetic heart valves. Some patients need both.

Current guidelines recommend that patients with CAD receive antiplatelet therapy with either aspirin or clopidogrel. Other antiplatelet drugs such as prasugrel (Effient), ticagrelor (Brilinta), or ticlopidine (Ticlid) may also be recommended. Sometimes two antiplatelet drugs (one of which is almost always aspirin) are prescribed for patients with unstable angina, ACS (unstable angina or early signs of heart attack), or those who have received a stent during PCI.

A thrombus is a blood clot that forms in a vessel and remains there. An embolism is a clot that travels from the site where it formed to another location in the body. Thrombi or emboli can lodge in a blood vessel and block the flow of blood in that location depriving tissues of normal blood flow and oxygen. This can result in damage, destruction (infarction), or even death of the tissues (necrosis) in that area.

Aspirin

Aspirin is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). It stops blood platelets, which are major clotting factors, from sticking together to form a blood clot. Aspirin therapy is extremely beneficial for patients with CAD or history of stroke.

If you have been diagnosed with CAD, your doctor may recommend that you take a daily dose (from 75 to 162 mg) of aspirin. A daily dose of 81 mg is recommended for patients who have undergone PCI (angioplasty). Aspirin can reduce the risk of heart attack and ischemic stroke. However, prolonged use of aspirin can increase the risks for stomach bleeding.

A daily low-dose aspirin (75 to 81 mg) is usually the first choice for preventing heart disease or stroke in high-risk individuals. Daily aspirin is not recommended for prevention in healthy people who are at low risk for heart disease. A doctor needs to consider a patient's overall medical condition and risk factors for heart attack before recommending aspirin therapy. Discuss with your doctor whether aspirin therapy is appropriate for you.

Clopidogrel

Thienopyridines are antiplatelet drugs. Clopidogrel (Plavix, generic) is the standard thienopyridine for patients with CAD. Other commonly used antiplatelet drugs used with aspirin are prasugrel (Effient) and Ticagrelor (Brilinta).

For heart disease primary and secondary prevention, daily aspirin is generally the first choice for antiplatelet therapy. Clopidogrel is prescribed instead of aspirin for patients who are aspirin allergic or who cannot tolerate aspirin. For most people, clopidogrel is not taken in combination with aspirin because the two drugs combined can increase the risk of bleeding. However, the combination is common in patients who have had a heart attack or who have received a stent.

Clopidogrel with aspirin is recommended for patients who are undergoing angioplasty with or without stenting. People who receive drug-coated stents require longer clopidogrel therapy, while those who receive bare-metal stents can maintain shorter duration therapy. People having coronary bypass surgery may be asked to hold their second, non-aspirin antiplatelet medication for several days prior to surgery because of a significant bleeding risk.

Aspirin and thienopyridine antiplatelet drugs like clopidogrel can increase the risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding, especially for people who have pre-existing ulcers or other risk factors. For this reason, some doctors recommend that people who are at high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding take a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) drug along with antiplatelet therapy.

PPI drugs help suppress gastric acid production, which in turn helps heal ulcers. However, certain PPI drugs may interfere with clopidogrel's antiplatelet effects. Discuss with your doctor the risks and benefits of taking a PPI drug along with clopidogrel and whether this is right for you.

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers are useful for preventing angina attacks and reducing high blood pressure. They reduce the heart's oxygen demand by slowing the heart rate and lowering blood pressure. They can help reduce risk of death from heart disease and from heart surgeries, including PCI and coronary bypass.

Beta blockers are used or recommended in a number of situations:

- They are started in nearly all patients who have just had a heart attack or ACS and are continued for at least 3 years.

- They are the drugs of choice for older people with stable angina and may also be beneficial for people with silent ischemia.

- They may be used alone or with other medications for management of rhythm disturbances or high blood pressure.

- They are a cornerstone of therapy for people with heart failure when the heart does not beat as strongly as normal.

Beta blockers include propranolol (Inderal), carvedilol (Coreg), bisoprolol (Zebeta), acebutolol (Sectral), atenolol (Tenormin), labetalol (Normodyne, Trandate), metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol-XL), and esmolol (Brevibloc). All of these drugs are available in generic form. A nasal spray form of propranolol may be helpful in reducing exercise-induced angina attacks.

If beta blocker therapy is not appropriate or not effective, a calcium channel blocker, nitrate, or ranolazine are alternative options.

Side Effects

Although most people tolerate them well, beta blocker side effects can include fatigue, lethargy, vivid dreams and nightmares, depression, memory loss, and dizziness. They can lower HDL ("good") cholesterol. Beta blockers are categorized as non-selective or selective. Non-selective beta blockers, such as carvedilol and propranolol, can narrow bronchial airways. These beta blockers may need to be avoided by people with asthma, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis.

People should never abruptly stop taking these drugs. The sudden withdrawal of beta blockers can rapidly increase heart rate and blood pressure. Your doctor may advise you to slowly decrease the dose before stopping completely.

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are important heart-protective drugs, particularly for people with diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart failure. They reduce the production of angiotensin, a chemical that causes arteries to narrow, and so are commonly used to lower blood pressure. They may also reduce risk for heart attack, stroke, complications of diabetes, and death in patients with or at high risk for heart disease.

ACE inhibitors are indicated for many people who have had heart attacks. They are particularly helpful for people with CAD who also have diabetes or who have heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction (when the heart's main chamber does not pump as well as it should).

ACE inhibitors include captopril (Capoten, generic), ramipril (Altace, generic), enalapril (Vasotec, generic), quinapril (Accupril, generic), benazepril (Lotensin, generic), perindopril (Aceon, generic), and lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril, generic).

Side Effects

Side effects of ACE inhibitors may include an irritating dry cough. More serious side effects are uncommon, but may include excessive drops in blood pressure, allergic reactions, and high blood potassium levels. If you cannot tolerate the side effects of ACE inhibitors, your doctor may prescribe an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) as an alternative high blood pressure drug with similar benefits.

Nitrates

Nitrates are used to control angina symptoms. Nitrates have been used in the treatment of angina for over 100 years. These drugs are vasodilators; they cause the release of nitric oxide, which relaxes the smooth muscles in blood vessels and allows blood to flow more easily. Many nitrate preparations are available. The most common are nitroglycerin, isosorbide dinitrate, and isosorbide mononitrate. Nitrates can be absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract (oral tablet), skin (ointment or patch), or from under the tongue (sublingual tablet or spray).

Rapid-Acting Nitrates

Rapid-acting nitrates are used to treat acute angina symptoms. Nitroglycerin is the most widely used drug for this purpose. It can be administered under the tongue (sublingually or as a spray) or pocketed between the upper lip and gum (buccally) and can relieve angina within minutes. The procedure for taking nitroglycerin during an attack is as follows:

- At the onset of an angina attack, the person sits or lies down and then administers one sublingual or buccal tablet or one metered dose of the spray.

- If the pain is not relieved within 5 minutes the person takes a second dose; a third can be taken after another 5 minutes if symptoms persist.

- If pain continues after a total of three doses in 15 minutes, the person should go immediately to the nearest emergency room or call 911 (they should not drive themselves).

Nitroglycerin is very unstable so its potency can be easily lost. Patients should take the following precautions:

- Keep no more than 100 tablets on hand, stored in their original container.

- When first opened, the cotton filler should be discarded, and the cap screwed on tightly immediately after each use.

- A supply should always be kept close at hand in case of an attack, with the rest kept in a cool dry place.

Intermediate to Long-Term Nitrates

Sublingual tablets of isosorbide dinitrate have a slower onset of action than nitroglycerin and are useful for preventing exertional (activity-induced) angina. Ointments, skin patches, and oral tablets are used for longer-term prevention of angina attacks:

- Transdermal skin patches are applied in the morning to any hair- or injury-free area on the chest, back, stomach, thigh, or upper arm. Hands should be washed after each patch or ointment application, and sites of application should be rotated to avoid skin irritation.

- Nitroglycerin ointment is applied by measuring out an even amount on an applicator paper and then placing, not rubbing or massaging, it on the chest, stomach, or thigh. Any ointment that remains from the previous application should be removed.

Long-acting forms may lose their effectiveness over time, so doctors generally schedule a daily nitrate-free break to prevent tolerance (usually overnight).

Side Effects

Nitrates can have many side effects, some of which can be serious.

Common side effects of nitrates include headaches, dizziness, nausea and vomiting, blurred vision, fast heartbeat, sweating, and flushing on the face and neck. Low blood pressure and dizziness can be relieved by lying down with the legs elevated. These effects are significantly worsened by alcohol, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and certain antidepressants.

The doctor may prescribe medicines to lessen these side effects. People should contact their doctor if these side effects are persistent or severe. People who take nitrates in any form should never take medications for erectile dysfunction, such as sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis), and avanafil (Stendra) because the combination can cause dangerously low blood pressure.

Serious side effects requiring immediate medical help include fever, joint or chest pain, sore throat, skin rash (especially on the face), unusual bleeding or bruising, weight gain, and swelling of the ankles.

Withdrawal

Withdrawal from nitrates should be gradual. Abrupt termination may cause angina attacks.

Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs)

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs) reduce heart rate and slightly dilate the blood vessels of the heart, thereby decreasing oxygen demand and increasing oxygen supply. They also reduce blood pressure. However, CCBs vary chemically. Although some are helpful, others may even be dangerous for certain patients with CAD.

- Long-acting nifedipine (Adalat, Procardia, generic) and nisoldipine (Sular, generic) and newer CCBs, such as amlodipine (Norvasc, generic) and nicardipine (Cardene, generic), are used to treat angina symptoms. They may be used alone for people who cannot tolerate beta blockers, or in combination with a beta blocker.

- Short-acting CCBs, including short-acting forms of verapamil, diltiazem, nifedipine, and nicardipine, are helpful for treating Prinzmetal's angina. However, short-acting forms of certain CCBs, such as nifedipine and nisoldipine, can cause severe and even dangerous side effects, including an increase in heart attacks and sudden death in people with stable or unstable angina. Short-acting CCBs are, therefore, not used for treating stable or unstable angina.

Side Effects

Patients with heart failure have a higher risk for death with these drugs and should not take them. No one should abruptly stop taking calcium channel blockers because sudden withdrawal can dangerously increase the risk of high blood pressure. Note: Grapefruit and Seville oranges boost the effects of certain CCBs, sometimes to toxic levels. (Regular oranges do not pose any hazard.)

Other Drugs

Ranolazine (Ranexa) is used to treat chronic angina in people who have not responded sufficiently to other angina drugs. Ranolazine is usually taken in combination with a calcium channel blocker, beta blocker, or nitrate drug.

Surgery

The two main procedural interventions for CAD are:

- PCI (percutaneous coronary intervention) also called angioplasty, which usually involves placing a stent

- CABG (coronary artery bypass graft surgery), which is a much more invasive surgical procedure

PCI and CABG are the standard procedures for dealing with narrowed or blocked arteries. PCI and CABG are revascularization procedures, which help restore blood flow (perfusion).

Angioplasty and Stenting (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention)

Angioplasty, also called PCI, involves procedures such as percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) that help open the blocked artery.

Angioplasty can help reduce the frequency of angina attacks for patients who have not been helped by drug therapy. It is commonly recommended for patients who have critically blocked arteries or have already had a recent, acute heart attack or unstable angina. However, symptom reduction is the main benefit of angioplasty in lower-risk people with stable CAD.

Evidence indicates that angioplasty works no better than intensive standard heart medication (drugs to control blood pressure, lower cholesterol, and prevent blood clots) in preventing heart attack, stroke, and hospitalization in people with stable CAD. For people with stable heart disease, drug therapy is usually sufficient enough treatment and allow them to safely defer having procedures.

Doctors now recommend angioplasty only for people who have difficult-to-control symptoms. However, some research suggests that CABG may be more effective than angioplasty in preventing heart attacks and death in people with blockage in several arteries.

Procedure

A typical angioplasty procedure follows these steps:

- After giving the person some mild sedating medications, the cardiologist threads a narrow catheter (a tube) through an artery from the groin or wrist area into the blocked vessel.

- The doctor opens the blocked vessel using balloon angioplasty by passing a tiny deflated balloon through the catheter to the vessel.

- The balloon is inflated to compress the plaque against the walls of the artery, flattening it out so that blood can once again flow through the blood vessel freely.

- To keep the artery open afterwards, doctors use a device called a coronary stent, an expandable metal mesh tube that is implanted during angioplasty at the site of the blockage. (In some cases, a stent may be used as the initial opening device instead of just balloon angioplasty.) The stent may be bare metal or it may be coated with a drug that slowly releases medication.

- Once in place, the stent pushes against the wall of the artery to keep it open.

Complications occur in about 5% to 10% of people (about 80% of them happening within the first day). Success rates are better in hospital settings with experienced teams and backup.

Recuperation and Complications

Angioplasty is less invasive than bypass surgery, usually requiring only one night in the hospital. Recuperation takes about a week. Chest pain after the procedure is common and usually due to problems other than ischemia. Mild chest pain is even more common when a stent is used, possibly because the artery is stretched.

The most important short- and long-term complication of angioplasty is acute closure of the artery by a clot (called "stent thrombosis"), which usually results in a serious heart attack and requires immediate treatment to clear the blockage. Stenting techniques, anti-clotting drugs, and other advances have significantly helped prevent re-closure and reduce heart attack rates. Another important condition is restenosis of the artery which is a different process involving the slower growth of tissue within the stent and causes symptoms over time. The desire to reduce this process which can result in the need for repeat procedures due to symptoms led to the development of drug-coated stents.

Drug-Coated Stents

Stents coated with sirolimus (Rapamune), paclitaxel (Taxol), or other drugs have been increasingly used in recent years. Drug-eluting stents (as they are also called) can help prevent restenosis. However, because drug-eluting stents reduce arterial tissue growth, they can increase the risks of acute blood clots that can block the stent (called "stent thrombosis"). Taking aspirin and an additional antiplatelet (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor) faithfully is critical to reducing the risk of this very serious complication.

Studies indicate that drug-eluting stents are safe and effective for people with CAD when they are used for FDA-approved indications. Some studies have indicated that problems may arise when these stents are used for "off-label" purposes in people with more complicated health problems, although other studies have found no increased risks. There is still some concern that all stents (both bare metal and drug eluting) may be used too frequently for people who may be better served by drugs or bypass surgery.

It is very important that people who have drug-eluting stents take aspirin and clopidogrel for the entire prescribed time, which may be as long as 1 year or more after the stent is inserted to reduce the risk of the stent clotting off. For people undergoing PCI who have ACS, two newer antiplatelet drugs, prasugrel (Effient) or ticagrelor (Brilinta), may be options. These drugs, like aspirin, help prevent blood platelets from clumping together.

If for some reason people cannot stick to a long-term dual antiplatelet regimen, they should receive a bare-metal stent instead of a drug-eluting stent after which the period of mandatory dual antiplatelet therapy may be as short as a month.

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery (CABG)

CABG surgery is an alternative to angioplasty (PCI) for many people with severe CAD. Studies suggest it is superior to PCI for people with multi-vessel disease (blockage in several arteries.) CABG is generally recommended instead of PCI for people with multiple blockages who have diabetes or heart failure.

Traditional CABG is an invasive open-heart surgical procedure. Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass surgery (MIDCAB), also called "keyhole heart surgery," may be an option for some people.

MIDCAB uses various techniques, including endoscopy or robotic-assisted approaches. Unlike standard CABG, with MIDCAB people do not have their heart stopped and therefore do not have to be put on a heart-lung machine during the procedure. In MIDCAB, the surgeon uses a smaller incision on the left side of the chest. CABG requires a longer incision down the center of the chest.

In a traditional CABG procedure:

- The chest is opened, and the blood is rerouted through a lung-heart machine.

- The heart is stopped during the procedure.

- Blood vessel grafts are taken from arteries or veins in the chest wall or other areas of the body such as the arm or leg. The grafts are transplanted and placed in the aorta at one end and beyond the blocked part of the arteries on the other end, so the blood flows through the new vessels around the blockage. People may require one, two, or three grafts (or more) depending on the number of coronary arteries that are blocked.

Complications

Complications are generally rare, but can include bleeding, infections, heart attack, and stroke. Finding a surgeon who performs at least 100 of the procedures a year helps reduce the risk for complications. The surgeon can advise you of the risk of complications based on your individual risk profile.

Blood clots may form in the new graft, closing it up or narrowing the treated vessel over time. Therapy with aspirin and other anti-clotting drugs help keep the graft open and working properly.

Recuperation and Rehabilitation

After leaving the hospital, people should have cardiac rehabilitation. Guidelines recommend that doctors refer people who have had CABG or PCI to a comprehensive outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program. Rehabilitation includes education about healthy diet and lifestyle choices, as well as exercise training to rebuild strength and stamina.

A cardiac rehabilitation program is coordinated by a multidisciplinary team that includes cardiologists, cardiac nurses, nutritional counselors, exercise physiologists, and others. The goal of cardiac rehabilitation is to help the person regain physical strength, improve heart and overall health, and reduce the future risks for heart attack or stroke.

Resources

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute -- www.nhlbi.nih.gov

- American Heart Association -- www.heart.org/en

- American College of Cardiology -- www.acc.org

References

Abbara S1, Blanke P2, Maroules CD, et al. SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: A report of the society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee: Endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(6):435-449. PMID: 27780758 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27780758/.

Abraham NS, Hlatky MA, Antman EM, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2010 Expert Consensus Document on the concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a focused update of the ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2010;122(24):2619-2633. PMID: 21060077 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21060077/.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. PMID: 30879355 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30879355/.

Brilakis ES, Patel VG, Banerjee S. Medical management after coronary stent implantation: a review. JAMA. 2013;310(2):189-198. PMID: 23839753 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23839753/.

Chamberlain JJ, Rhinehart AS, Shaefer CF Jr, Neuman A. Diagnosis and management of diabetes: Synopsis of the 2016 American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2016:164(8):542-552. PMID: 26928912 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26928912/.

Drozda J Jr, Messer JV, Spertus J, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with coronary artery disease and hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):316-336. PMID: 21676572 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21676572/.

Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC Guideline on Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2960-2984. PMID: 24239922 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239922/.

Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(25):2375-2384. PMID: 23121323 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23121323/.

Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(18):1929-1949. PMID: 25077860 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077860/.

Fleg JL, Forman DE, Berra K, et al. Secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in older adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128(22):2422-2446. PMID: 24166575 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24166575/.

Goff Jr DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935-2959. PMID: 24239921 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24239921/.

Gulati M, Bairey Merz CN. Cardiovascular disease in women. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 89.

Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):e123-e210. PMID: 22070836 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22070836/.

Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1221-1231. PMID: 27028912 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27028912/.

Kulik A, Ruel M, Jneid H, et al. Secondary prevention after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(10):927-964. PMID: 25679302 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25679302/.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):e44-e122. PMID: 22070834 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22070834/.

Levine GN, Steinke EE, Bakaeen FG, et al. Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(8):1058-1072. PMID: 22267844 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22267844/.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(5):1243-1275. PMID: 27751237 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27751237/.

Lin JS, Evans CV, Johnson E, et al. Nontraditional Risk Factors in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320(3):281-297. PMID: 29998301 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29998301/.

Morrow DA, de Lemos JA. Stable ischemic heart disease. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 61.

Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women--2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(11):1243-1262. PMID: 21325087 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21325087/.

Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for coronary heart disease with electrocardiography: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):512-518. PMID: 22847227 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22847227/.

Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin, mineral, and multivitamin supplements for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(8):558-564. PMID: 24566474 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24566474/.

Patel MR, Calhoon JH, Dehmer GJ, et al. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/STS 2017 appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24(5):1759-1792. PMID: 28608183 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28608183/.

Ridker PM, Libby P, Buring JE. Risk markers and the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, Tomaselli GF, Braunwald E, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 45.

Rosendorff C, Lackland DT, Allison M, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. Circulation. 2015;131(19):e435-e470. PMID: 25829340 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25829340/.