Alzheimer disease - InDepth

Highlights

Alzheimer Disease

Dementia is significant loss of cognitive functions such as memory, judgment, attention, and abstract thinking. Alzheimer disease is the most common form of dementia. It is a progressive brain disease. It affects more than 5 million Americans, and millions more worldwide.

Risk Factors

Age is the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer disease. Most people who develop Alzheimer disease are 65 years old or more, and the risk increases with age. People age 85 years and older are largely at risk for Alzheimer disease.

Symptoms

Early symptoms of Alzheimer disease may include:

- Forgetfulness

- Loss of concentration

- Language problems

- Confusion about time and place

- Impaired judgment

- Loss of insight

- Impaired movement and coordination

- Mood and behavior changes

- Apathy and depression

Treatment

There is no cure for Alzheimer disease. Drug therapy aims to treat symptoms associated with the disease. The benefit from drugs used to treat Alzheimer disease is typically small. Patients and their families may not notice any benefit.

Patients and their families need to discuss with their doctors whether drug therapy can help improve behavior or functional abilities. They also need to discuss whether or not drugs should be prescribed early in the course of the disease or delayed.

The following drugs are commonly prescribed for treatment of Alzheimer disease:

- Donepezil (Aricept, generic)

- Rivastigmine (Exelon, generic)

- Galantamine (Razadyne, generic)

- Memantine (Namenda, generic)

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among older people. Dementia is the medical term for loss of cognitive functions including memory, judgment, attention, and abstract thinking

AD is a progressive and incurable degenerative disease of the brain. AD begins slowly. It first involves the parts of the brain that control thought, memory, and language.

The disease slowly attacks nerve cells in all parts of the cortex of the brain and some surrounding structures, thereby impairing a person's abilities to govern emotions, recognize errors and patterns, coordinate movement, and remember. The changes in the brain may begin to develop more than 20 years before symptoms develop. Ultimately, a person with AD loses memory and many other mental functions.

There are three brain abnormalities that are the hallmarks of the AD process:

- Plaques. A protein called beta-amyloid accumulates and forms sticky clumps of amyloid plaque between nerve cells (neurons). High levels of beta amyloid are associated with reduced levels of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. (Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers in the brain.) Acetylcholine is part of the cholinergic system, which is essential for memory and learning.

- Tangles. Neurofibrillary tangles are the damaged remains of a protein called tau, which in its normal version helps maintain microtubules within healthy neurons. (Microtubules are hollow rods within cells that support their shape and structure.)

- Loss of nerve cell connections. The tangles and plaques cause neurons to lose their connection to one another and die off. As the neurons die, brain tissue shrinks (atrophies).

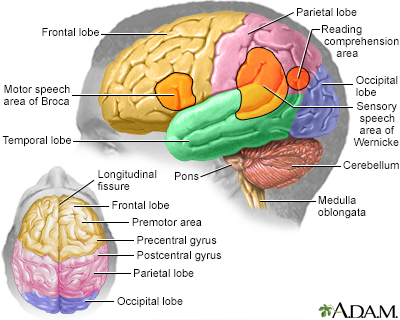

The major areas of the brain have one or more specific functions.

Stages of Alzheimer Disease

Although no cure has been found for Alzheimer, scientists are making advances in better understanding the disease and how it progresses. The U.S. National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association has criteria for defining and diagnosing Alzheimer. It classifies the disease into three stages:

- Preclinical. In this stage, brain changes including amyloid buildup and nerve cell disruption are beginning to occur but symptoms are not yet evident. Researchers are studying various tests for biomarkers to better understand what these changes mean and what type of risk they may pose for progression to Alzheimer dementia.

- Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). MCI is marked by symptoms of memory problems but they are not severe enough to interfere with a person's functioning or independence. People with MCI may or may not go on to develop Alzheimer dementia. Biomarker tests to better identify this stage are currently being developed.

- Alzheimer Dementia. This stage encompasses the spectrum of dementia severity from mild to severe. Symptoms are apparent and have gradually become worse over months or years. They are now significant enough to affect daily functional abilities. The most typical symptom is memory loss, particularly the learning and recall of recent information. Other symptoms may include difficulties in finding words, identifying and locating objects and faces, and problems with judgment and reasoning.

Causes

Scientists do not know what causes AD. It may be a combination of various genetic and environmental factors that trigger the process in which brain nerve cells are destroyed.

Genetic Factors

Genetics certainly plays a role in early-onset Alzheimer, a rare form of the disease that often runs in families. Three genes have been associated with early-onset Alzheimer:

- Amyloid precursor protein (APP)

- Presenilin 1

- Presenilin 2

Scientists are also investigating genetic targets for late-onset Alzheimer, which is the more common form.

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is the main gene that has been definitively linked to late-onset Alzheimer disease. It is estimated that 20-30% of people in the US carry the form of ApoE (ApoE e4) that increases the risk for late-onset Alzheimer, and approximately 2% of the US population carries both copies of ApoE e4. Other genes or combinations of genes may be involved.

Environmental Factors

Researchers have investigated various environmental factors that may play a role in AD or may trigger the disease process in people who have a genetic susceptibility. Some studies have suggested an association between serious head injuries in early adulthood and Alzheimer development. Lower educational level, which may decrease mental and activity and neuron stimulation, has also been investigated. To date, there does not appear to be any evidence that infections, metals, or industrial toxins cause AD.

Risk Factors

AD is the fifth leading cause of death in American adults age 65 and older. It affects more than 5 million Americans and more than 40 million people worldwide.

Age

Age is the primary risk factor for AD. The number of cases of AD doubles every 5 years beyond age 65. According to the U.S. Alzheimer's Association, nearly 1 in 3 people age 85 years and older have the disease. While less common, AD can also affect younger people. About 200,000 Americans younger than age 65 have early-onset Alzheimer disease.

Sex

More women than men develop AD but this is most likely because women tend to live longer than men. According to the Alzheimer's Association, nearly two thirds of patients with AD are women. Women in their 60s are more likely to develop AD during their lifetimes than breast cancer.

Race and Ethnicity

African Americans and Hispanics are at greater risk of developing Alzheimer disease than non-Hispanic whites. This may be in part because they have a higher prevalence of medical conditions such as high blood pressure and diabetes, which are associated with increased risk for Alzheimer. Genetic factors may also play a role.

Family History

Having a first-degree relative (parent, brother, sister) with AD increases your risk for the disease. Having more than one first-degree relative with AD further increases risk.

Serious Head Injury

A history of traumatic brain injury, including a concussion, is a risk factor for AD.

Heart and Vascular Diseases

There is growing evidence that diseases that affect the heart and vascular (blood vessel) system increase the risk for AD. The brain requires a steady supply of oxygen-rich blood, which is supplied by a healthy pumping heart and adequate blood flow throughout the body. Conditions associated with heart and circulatory problems include high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and type 2 diabetes. There is some evidence that controlling these conditions may help prevent AD.

Lifestyle Factors

Clinical trials have evaluated numerous substances for preventing AD but have not found any of them to be helpful. They included nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), statin drugs, estrogen replacement therapy, folic acid supplementation, vitamin E, fish oil supplements, and herbal remedies such as ginkgo biloba.

However, certain lifestyle changes may help in AD prevention:

- Stay mentally active. Participating in intellectually engaging activity (such as doing crossword puzzles or learning a new language) may help reduce the risk for AD.

- Stay physically active. Exercise and regular physical activity of at least moderate intensity are important for heart and vascular health and may help preserve cognitive function.

- Stay socially active. Personal relations and connections may help protect against AD.

- Eat a heart-healthy and brain-healthy diet. While no specific dietary factors have been found to prevent AD, a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet is healthy for the heart and the brain. Replace saturated fats and trans-fatty acids with unsaturated fats from plant and fish oils. Fish oil's omega-3 fatty acids, which contain docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are an excellent source of unsaturated fat. Eat lots of darkly colored fruits and vegetables, which are the best source for antioxidant vitamins and other nutrients. (Although there has been much research, there is no evidence that vitamin B or E supplements, or fish oil supplements, are protective. Food is the best source for these nutrients.) The Mediterranean diet is an example of an eating plan that includes many of these recommendations.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Obesity is associated with a more sedentary lifestyle, which is a risk factor for AD. Obesity also increases the risk for heart and metabolic conditions that may be associated with AD development, such as diabetes.

- Avoid heavy alcohol use. Heavy drinking is associated with an increased risk for AD.

- Avoid using any illicit and habit-forming drugs. These drugs can further damage the memory and worsen the manifestations of AD.

- Sleep enough every night. Sleeping for at least 7 to 8 hours every night is important for better functioning of the brain.

Symptoms

The early symptoms of Alzheimer disease (AD) may be overlooked because they resemble signs of natural aging. However, extreme memory loss or other cognitive changes that disrupt normal life are not typical signs of aging. In addition, the symptoms of AD do not begin abruptly; they develop gradually and worsen over the course of months or years.

Older adults who begin to notice a persistent mild memory loss of recent events may have a condition called mild cognitive impairment (MCI). MCI may be a sign of early-stage AD in older people. Studies suggest that some, although not all, older individuals who experience such mild memory abnormalities can later develop AD.

Patients may be aware of their symptoms or may be unaware that anything is wrong. The Alzheimer's Association recommends that everyone learn these 10 warning signs of AD:

- Memory changes that disrupt daily life. Forgetfulness, particularly of recent events or information, or repeatedly asking for the same information.

- Challenges in planning or solving problems. Loss of concentration (having trouble planning or completing familiar tasks, difficulty with abstract thinking such as simple arithmetic problems).

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work, or at leisure.

- Confusion about time or place. Difficulty recognizing familiar neighborhoods or remembering how you arrived at a location, confusion about months or seasons.

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. Difficulty reading, figuring out distance, or determining color.

- Language problems. Forgetting the names of objects, mixing up words, difficulty completing sentences or following conversations.

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. Putting objects back in unusual places, losing things, accusing others of hiding or stealing.

- Impaired judgment and decision making. Dressing inappropriately or making poor financial decisions.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities. No longer participating in familiar hobbies and interests.

- Mood and personality changes. Confusion, increased fear or suspicion, apathy and depression, anxiety. Signs can be loss of interest in activities, increased sleeping, sitting in front of the television for long periods of time.

Diagnosis

AD is typically diagnosed clinically, based on the medical history and physical examination. It used to be said that the only definitive diagnosis of AD can be made after death if an autopsy of the brain is performed. However, AD diagnosis is a very active area of research, with the objective to diagnose AD while it is still in its early stages.

Researchers are making progress studying biomarkers, chemical substances that signal changes in the brain associated with AD. In a recent study of biomarkers, scientists found that measuring levels of amyloid beta and tau proteins in brain imaging scans and spinal fluid may help predict the development of AD many years before symptoms begin.

The scientific community is working on standardizing the use of biomarkers to aid in the early detection of AD while it is in its preclinical or mild cognitive impairment stages. Biomarkers may also eventually help doctors evaluate how the disease progresses. However, at present, biomarker testing is only used in research settings or to supplement the standard clinical tests. Doctors use a variety of standardized clinical tests to make a probable diagnosis of AD.

Currently, no test can predict which patients in the preclinical or mild cognitive impairment will progress to AD dementia.

Medical History and Physical Examination

The doctor will ask about the patient's health history, including other medical conditions the patient has, recent or past illnesses, and progressive changes in mental function, behavior, or daily activities. The doctor will ask about use of prescription drugs (it is helpful to bring a complete list of the patient's medications) and lifestyle factors, including diet and use of alcohol. The doctor will evaluate the patient's hearing and vision, and check blood pressure and other physical signs. A neurological test will also be conducted to check reflexes, coordination, and eye movement.

Laboratory Tests

Blood and urine samples may be collected. They can help the doctor evaluate other possible causes of dementia, such as thyroid imbalances or vitamin deficiencies. Researchers are studying measuring levels of amyloid beta and tau proteins in spinal fluid samples to help identify patients with memory problems who may be at risk for developing AD.

Neuropsychological Tests

Several psychological tests are used to assess difficulties in attention, perception, memory, language, problem-solving, social, and language skills. These tests can also be used to evaluate mood problems such as depression. Because depression may mimic symptoms of dementia, neuropsychological testing may be useful in determining if symptoms are due to depression, dementia, or both.

Two commonly used tests are the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). These tests use a series of questions and tasks to evaluate cognitive function. For example, the patient is given a series of words and asked to recall and repeat them a few minutes later. In the clock-drawing test, the patient is given a piece of paper with a circle on it and is asked to write the numbers in the face of a clock and then to show a specific time on the clock.

Brain-Imaging Scans

Imaging tests are useful for ruling out blood clots, tumors, or other structural abnormalities in the brain that may be causing signs of dementia. These tests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or positron-emission testing (PET) scans.

Researchers are using MRIs and PET scans to study new approaches to diagnosing AD in earlier stages of the disease. Methods include measuring the volume and shrinkage (atrophy) of brain tissue with MRI and evaluating the brain's use of glucose with PET.

Since 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 radioactive diagnostic drugs that are used with PET scans to evaluate beta amyloid density. They are florbetapir (Amyvid), flutemetamol (Vizamyl), and florbetaben (Neuraceq). Patients with AD have a high build-up of amyloid plaques in the brain. However, high amyloid plaque density is also found in some patients with normal cognitive function as well as those who have dementias not related to AD. If PET scans using these drugs do not show amyloid accumulation in the brain, a person's symptoms are unlikely due to AD.

Ruling out Other Causes of Memory Loss or Dementia

AD is the most common cause of dementia. Other causes of dementia in older people can include:

- Vascular dementia (abnormalities in the vessels that carry blood to the brain)

- Lewy body variant (LBV), also called dementia with Lewy bodies

- Parkinson disease

- Frontotemporal dementia

Vascular Dementia

Vascular dementia is primarily caused by either multi-infarct dementia (multiple small strokes) or Binswanger disease (which affects tiny arteries in the midbrain).

Lewy Body Variant

Lewy bodies are abnormalities found in the brains of patients with both Parkinson and AD. They can also be present in the absence of either disease; in such cases, the condition is called Lewy body variant (LBV). In all cases, the presence of Lewy bodies is highly associated with dementia.

Parkinson Disease

Some of the symptoms of Parkinson and AD can be similar and the diseases may coexist.

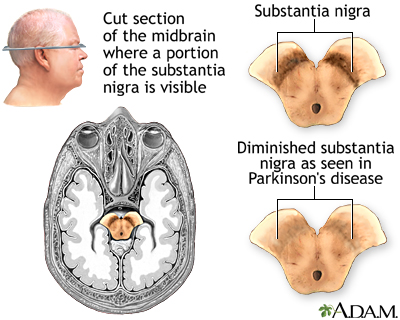

Parkinson disease is a slowly progressive disorder that affects movement, muscle control, and balance. Part of the disease process develops as cells are destroyed in certain parts of the brain stem, particularly the crescent-shaped cell mass known as the substantia nigra. Nerve cells in the substantia nigra send out fibers to tissue located in both sides of the brain. There the cells release essential neurotransmitters that help control movement and coordination. About a third of people with Parkinson disease will develop dementia. However, unlike AD, language is not usually affected in Parkinson dementia.

Frontotemporal Dementia

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a term used to describe a group of disorders that affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. Although some of the symptoms can overlap with AD, people who develop this condition tend to be younger than most patients with AD.

Other Conditions

A number of conditions, including many medications, can produce secondary dementia, with symptoms similar to Alzheimer. These conditions include severe depression, drug abuse, thyroid disease, vitamin deficiencies, blood clots, infections, brain tumors, and various neurological or vascular disorders.

Treatment

There is no cure for Alzheimer disease (AD) or treatment to stop its progression or reverse the symptoms. Most drugs used to treat Alzheimer are aimed at slowing the rate at which symptoms become worse, and prolonging a person's ability to remain independent. The benefit from these drugs is generally small, and patients and their families may not even notice any benefit.

Stages

AD is classified into various stages that range from mild to moderate to severe. In the final stages of AD, the patient is unable to communicate and is completely dependent on others for care.

The lifespan of patients with AD is generally reduced, although a patient may live anywhere from 4 to 20 years after diagnosis. The final phase of the disease may last from a few months to several years, during which time the patient becomes increasingly immobile and dysfunctional.

Treatment Considerations

Most people with AD are cared for at home, largely during the early stages of the disease. Caregiving is an enormous commitment. Support services can greatly improve the quality of life for both caretakers and their patients and make it easier for people to continue caring for patients in their homes. These services include home healthcare aides and adult day care.

As AD progresses, round-the-clock care is largely required. At this point, the family needs to decide whether in-home treatment can be continued or whether placement in a nursing home or assisted living facility is a feasible option. In choosing a facility, it is best to select one that is specialized in the care of people with AD and equipped to meet their needs.

Medications

Most drugs used to treat AD, and those under investigation, are aimed at slowing progression. At this time, there is no cure. In addition, the improvements from some of these drugs may be so modest that patients and their families may not notice any benefit.

The FDA has approved two drug classes to treat the cognitive symptoms of AD:

- Cholinesterase inhibitors (generally used to treat mild-to-moderate AD; donepezil is also approved for treatment of severe dementia)

- N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists (used to treat moderate-to-severe AD)

While these drugs do not have generally serious risks, they can cause a number of bothersome side effects, including indigestion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite, muscle cramps, and fatigue.

Patients and caregivers should ask their doctors the following questions about when and if to use these drugs:

- Will there be a noticeable change in behavior or function of the patient? The published studies that enabled approval of these drugs for treatment of AD demonstrated modest benefit when evaluating patients using cognitive and functional scales. While these scales are important for consistency of recording and performing studies, the benefit demonstrated in clinical trials does not necessarily translate into any significant change in how patients function in their daily lives. There is, in fact, no evidence that use of these medications extends the time before a person requires care in an institutional setting, such as a nursing home.

- Is it better to use these drugs early in the course of Alzheimer disease? Treating people with mild cognitive impairment (persistent mild memory loss of recent events but no diagnosis of AD) does not seem to prevent them from developing AD.

- If there are no signs of improvement, when should a drug be discontinued? Define goals with the patient's doctor, and establish a timeline for how long a drug should be tried and when it should be stopped.

Cholinesterase Inhibitors (Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine)

Cholinesterase inhibitors are designed to protect the cholinergic system, which is essential for memory and learning and is progressively destroyed in AD. These drugs work by preventing the breakdown of the brain chemical acetylcholine, which is reduced in the brains of AD patients.

The three most commonly prescribed cholinesterase inhibitors for AD are donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine:

- Donepezil. Donepezil (Aricept, generic) is the only AD drug approved for all stages of dementia, from mild to severe. It is taken once a day and has only modest benefits at best.

- Rivastigmine. Rivastigmine (Exelon, generic) targets two enzymes: Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. It is available in pill form and also available as a skin patch. It is approved for mild-to-moderate AD. A higher-dose skin patch is approved for patients with severe AD.

- Galantamine. Galantamine (Razadyne, generic) in addition to inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, also directly stimulates acetylcholine receptors. It is approved to treat mild-to-moderate AD.

Side Effects

All three have similar efficacy. Common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors, largely when taken in higher doses, may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and upset stomach. Rivastigmine and galantamine tend to have more side effects than donepezil, and may also cause weight loss and loss of appetite. Cholinesterase inhibitors may increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers, largely when used with NSAIDs (which can also cause gastric irritation). The patch form of rivastigmine may have fewer GI side effects than the oral form for some patients.

Some drugs known as anticholinergics may offset the effects of the AD pro-cholinergic drugs. Such drugs include antihistamines, antipsychotic drugs, and some antidepressants and anti-incontinence drugs.

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) Receptor Antagonist (Memantine)

Memantine (Namenda) is approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe AD. (It does not appear to be effective for mild AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors are used to treat mild-to-moderate stages of the disease.) By blocking NMDA receptors, memantine protects against overstimulation by glutamate, an amino acid that excites nerves and that, in excess, is a powerful nerve-cell killer.

Memantine is prescribed either alone or in combination with donepezil. Studies indicate that memantine may help modestly improve cognitive function and delay the progression of AD for up to 1 year. Side effects are generally mild but may include dizziness, drowsiness, or fainting.

Treating Symptoms Associated with Alzheimer Disease

Depression

Antidepressants known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including fluoxetine (Prozac, generic) and sertraline (Zoloft, generic), may help reduce depression, irritability, and restlessness associated with Alzheimer in some patients.

Apathy

Depression is often confused with apathy. An apathetic patient lacks emotions, motivation, interest, and enthusiasm while a depressed patient is generally very sad, tearful, and hopeless. Apathy may respond to stimulants, such as methylphenidate (Ritalin, generic), rather than antidepressants.

Psychosis

Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat verbally or physically aggressive behavior and hallucinations. Because older antipsychotic drugs, such as haloperidol (Haldol, generic), have severe side effects, most doctors now prescribe newer atypical antipsychotics, such as risperidone (Risperdal, generic) or olanzapine (Zyprexa, generic).

However, these newer antipsychotic drugs can cause serious side effects, including confusion, sleepiness, and Parkinsonian-like symptoms. In addition, studies indicate that their safety risks may outweigh any possible benefits. Studies show that both atypical and older antipsychotics produce a slightly increased rate of death in patients with AD or dementia and that atypical antipsychotics work no better than placebo in controlling psychosis, aggression, and agitation in patients with AD.

The American Psychiatric Association and the American Geriatrics Society recommend against prescribing antipsychotic medication to patients with dementia unless absolutely necessary. They recommend first trying behavioral treatments and controlling changes in the patient's environment and routine.

Disturbed Sleep

Patients with AD commonly experience disturbances in their sleep/wake cycles. Moderately short-acting sleeping drugs, such as temazepam (Restoril, generic), zolpidem (Ambien, generic), or zaleplon (Sonata, generic), or sedating antidepressants, such as trazodone (Desyrel, generic), may be useful in managing insomnia. However, these drugs increase the risk of falling, confusion, and abnormal behavior and must be used with considerable caution and restraint.

Some research suggests that exposure to brighter-than-normal artificial light during the day for patients with normal vision may help reset wake/sleep cycles and prevent nighttime wandering and sleeplessness. Sleep hygiene methods (regular times for meal and bed, exercise, avoiding caffeine) can also be helpful.

Caregiving

Caregivers of people with AD face enormous challenges. Few diseases disrupt patients and their families so completely or for so long a period of time as AD. The following tips may help caregivers better cope with some of the issues and behaviors associated with this disease.

Personality Changes and Communication

There is no single AD personality, just as there is no single human personality. All patients must be treated as the individuals they continue to be, even after their social self has vanished.

Patients with AD often display abrupt mood swings, and some become aggressive and angry. Some of this erratic behavior is caused by chemical changes in the brain. But it may also be due to the experience of losing knowledge and understanding of one's surroundings, causing fear and frustration that patients can no longer express verbally.

The following recommendations for caregivers may help soothe patients and avoid agitation:

- Establish a daily routine for getting up, meal times, bathing, and other activities to help patients have a sense of comfort and familiarity.

- Keep environmental distractions and noise (television, radio) at a minimum if possible. (Even normal noises, such as people talking outside a room, may seem threatening and trigger agitation or aggression.)

- Speak clearly in a gentle tone of voice using simple words and short sentences. Allow enough time for a response.

- Offer diversions, such as a snack or car ride, if the patient starts shouting or exhibiting other disruptive behavior.

- Maintain as natural an attitude as possible. Patients with AD can be highly sensitive to the caregiver's underlying emotions and react negatively to patronization or signals of anger and frustration.

- Showing movies or videos of family members and events from the patient's past may be comforting.

Although much attention is given to the negative emotions of patients with AD, some patients become extremely gentle, retaining an ability to laugh at themselves or appreciate simple visual jokes even after their verbal abilities have disappeared. Some patients may seem to be in a drug-like or "mystical" state, focusing on the present experience as their past and future slip away. Encouraging and even enjoying such states may bring comfort to both the patient and the caregiver.

Bathing and Dressing

Hygiene and grooming can be major challenges for caregivers. Many patients resist bathing or taking a shower. Some patients find bathing confusing or frightening. Some spouses find that showering with their afflicted mate can solve the problem for a while. Establishing a daily and familiar routine can be helpful.

Often patients with AD lose their sense of color and design and will put on odd or mismatched clothing. It is important to maintain a sense of humor and perspective and to learn which battles are worth fighting and which ones are best abandoned. Caregivers can pick a selection of outfits and allow the patient to select a favorite. Try to choose clothes that are easy to put on and take off.

Eating and Drinking

Weight loss and the gradual inability to swallow are two major related problems in late-stage AD and are associated with an increased risk for death. As AD progresses, patients may change their food preferences or find some kinds of foods more difficult to eat. Try different foods and be sure to allow enough time for the patient to eat. Limit distractions around mealtimes. Because choking is a danger, you should learn how to administer the Heimlich maneuver. Dehydration can also become a problem. It is important to encourage fluid intake equal to 8 cups of water daily. Coffee and tea are mild diuretics that may deplete fluid.

Driving

Patients at any stage of dementia, including mild, are at high risk for unsafe driving. Some of the typical symptoms of AD, such as difficulty remembering and navigating locations, poor judgment, and slow decision making, all pose dangers for driving. A recent history of citations, crashes, or aggressive or reckless driving is a specific warning sign of unsafe driving. As soon as AD is diagnosed, the patient should be prevented from driving. This includes hiding car keys. For patients with early stage AD, it is helpful to plan ahead for the time they will no longer be able to drive. This includes arranging for caregivers to drive and exploring other transportation options, while attempting to preserve the patients' independence and ensuring their safety. In some states, there are requirements to report drivers who are unsafe due to Alzheimer or other conditions. Special therapists can perform a driving safety assessment, if needed.

Wandering

Wandering is a common problem. As memory problems worsen, patients may become easily confused, disoriented, and lost. The following precautions are recommended:

- Locks should be installed outside the door, which the caregiver can open, but the patient cannot.

- Alarms may be installed at exits.

- Plan daily activities and distractions to coincide with the times of day that the patient seems prone to wandering. This can be as simple as giving the patient a household task like folding towels.

- Daily exercise can help give the patient a chance to burn off energy and sleep better at night.

- Make sure the patient is not wandering due to hunger, thirst, or needs to use a bathroom.

- Consider enrolling the patient in a program such as the Alzheimer's Association's Medic Alert and Safe Return, which provides identification supplies and procedures that help locate patients who wander away from home and become lost.

Incontinence

Incontinence (loss of control of bowel or urine function) is one of the main reasons why many caregivers decide to seek nursing home placement. When the patient first shows signs of incontinence, the doctor should make sure that it is not caused by an infection. Urinary incontinence may be controlled for some time by trying to monitor times of liquid intake, feeding, and urinating. Once a schedule has been established, the caregiver may be able to anticipate incontinent episodes and get the patient to the toilet before they occur.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common cause of urinary incontinence. UTIs can also cause behavioral changes, and worsen aggression and confusion symptoms. Antibiotics are used to treat UTIs.

Immobility

As the disease progresses to later stages, patients become immobile, literally forgetting how to move. Eventually, they become almost entirely wheelchair-bound or bedridden. Bedsores can be a major problem. Sheets must be kept clean, dry, and free of food. The patient's skin should be washed frequently, gently blotted thoroughly dry, and moisturizers applied. Try to move the patient every few hours and keep their feet raised with pillows or pads. Manipulation exercises can help keep legs and arms flexible.

Care for the Caregiver

Caregiving for a loved one with AD is undoubtedly stressful. Most patients with AD are cared for at home by family members, who often lack adequate support, finances, or training for this difficult job.

It is important for caregivers to recognize and take care of their own physical and emotional needs. Depression, exhaustion, guilt, and anger can lead to caregiver burnout as well as poor health.

Seek out support from family, friends, and professional associations. Such support includes individual and family counseling, support groups, and stress management and problem-solving techniques.

Resources

- Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center (U.S. National Institute on Aging) -- www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers

- Alzheimer's Association -- www.alz.org

- Alzheimer's Disease International -- www.alz.co.uk

- American Academy of Neurology -- www.aan.com

- Medic Alert -- www.medicalert.org

- Find clinical trials -- www.clinicaltrials.gov

- Find a nursing home -- www.medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare/search.html

References

AGS Choosing Wisely Workgroup. American Geriatrics Society identifies another five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):950-960. PMID: 24575770 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24575770/.

AGS Choosing Wisely Workgroup. American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):622-631. PMID: 23469880 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23469880/.

Albert MS, Dekosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279. PMID: 21514249 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21514249/.

Alzheimer's Association website. 2018 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):367-429. www.alz.org/media/homeoffice/facts%20and%20figures/facts-and-figures.pdf.

Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and management of dementia: review. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589-1599. PMID: 31638686 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31638686/.

Bang J, Spina S, Miller BL. Frontotemporal dementia. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1672-1682. PMID: 26595641 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26595641/.

Birks JS1, Grimley Evans J. Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD001191. PMID: 25858345 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25858345/.

Burckhardt M, Herke M, Wustmann T, Watzke S, Langer G, Fink A. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD009002. PMID: 27063583 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27063583/.

Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD011145. PMID: 26760674 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26760674/.

Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, et al. Proceedings of the Meeting of the International Working Group (IWG) and the American Alzheimer's Association on "The Preclinical State of AD"; July 23, 2015; Washington DC, USA. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):292-323. PMID: 27012484 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27012484/.

Hampel H, O'Bryant SE, Molinuevo JL, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: mapping the road to the clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(11):639-652. PMID: 30297701 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30297701/.

Jack CR Jr, Albert MS, Knopman DS, et al. Introduction to the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7(3):257-262. PMID: 21514247 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21514247/.

Knopman DS. Cognitive impairment and dementia. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2020:chap 374.

Martínez G, Vernooij RW, Fuentes Padilla P, Zamora J, Bonfill Cosp X, Flicker L. 18F PET with florbetapir for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD012216. PMID: 29164603 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29164603/.

McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(1):CD003160. PMID: 26727124 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26727124/.

McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Malouf R, Passmore P. Statins for the treatment of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(7):CD007514. PMID: 25004278 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25004278/.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. PMID: 21514250 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21514250/.

Mendez MF. Early-onset Alzheimer disease. Neurol Clin. 2017;35(2):263-281. PMID: 28410659 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28410659/.

Mitchell SL. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2533-2540. PMID: 26107053 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26107053/.

Molinuevo JL, Ayton S, Batrla R, et al. Current state of Alzheimer's fluid biomarkers. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(6):821-853. PMID: 30488277 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30488277/.

Olivari BS, Baumgart M, Lock SL, et al. CDC grand rounds: promoting well-being and independence in older adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(37):1036-1039. PMID: 30235185 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30235185/.

Peterson R, Graff-Radford J. Alzheimer disease and other dementias. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff’s Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 95.

Rosenberg RN, Lambracht-Washington D, Yu G, Xia W. Genomics of Alzheimer disease: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(7):867-874. PMID: 27135718 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27135718/.

Sharma K. Cholinesterase inhibitors as Alzheimer's therapeutics (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2019;20(2):1479-1487. PMID: 31257471 pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31257471/.

|

Review Date:

3/29/2021 Reviewed By: Joseph V. Campellone, MD, Department of Neurology, Cooper Medical School at Rowan University, Camden, NJ. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team. |

© 1997- A.D.A.M., a business unit of Ebix, Inc. Any duplication or distribution of the information contained herein is strictly prohibited.